What Are Fat Fingers and Why Don’t They Go Away?

Even the best-laid plans and systems can’t account for human fallibility.

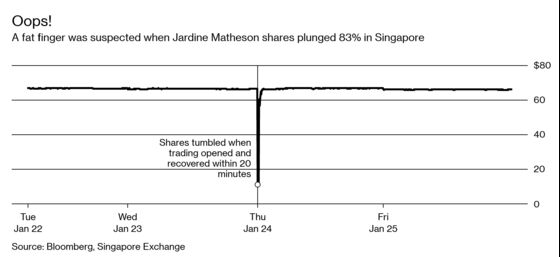

(Bloomberg) -- A momentary 83 percent plunge and rebound in one of Singapore’s largest stocks, Jardine Matheson Holdings Ltd., left dazed traders wondering whether a “fat finger” had struck again in January. After the dust settled, Singapore Exchange Ltd. decided not to cancel the trades, insisting neither human error nor a computer malfunction was to blame. Still, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley were said to have sought to cancel or amend their trades later, indicating mistakes were made somewhere. The episode serves as a reminder that even the best-designed systems can behave unexpectedly once humans enter the equation.

1. What’s a fat finger?

For the origin of the phrase, imagine someone entering a trade and pressing the button next to the one he or she meant to on the keyboard -- literally because his or her finger was too big -- and you get the idea. It’s become a colloquialism that refers generally to human error, either a literal typing error or a more figurative mistake. As many financial institutions have discovered over the years, an extra zero here or there can make a huge difference.

2. Can mistakes be reversed later?

In many cases, yes. Deutsche Bank AG accidentally transferred 28 billion euros ($32 billion) -- far more than was due -- to an outside account as part of its daily derivative dealings, Bloomberg first reported in April 2018. The money landed at Deutsche Boerse AG’s Eurex clearinghouse, but was quickly returned. Volume in Walt Disney Co. appeared to surge for a moment in February 2015 when more than 131 million shares seemed to trade at once on the New York Stock Exchange -- a transaction so big only one shareholder probably could have placed it. But it turned out it never happened, as the initial trade order was quickly cut to a much less magical 1.3166 million.

3. So fat fingers don’t hurt everyone?

Not necessarily. Someone at Samsung Securities Co., one of South Korea’s largest brokerages, was trying to pay employees 1,000 won (88 cents) per share in dividends under a company compensation plan in April 2018, but gave them 1,000 shares instead. That totaled about $105 billion, or more than 30 times the company’s market value. Things got worse when 16 employees sold the stock, sparking a rout in the share price. In December 2015, Mizuho Securities Co. in Japan mistakenly offered to sell 610,000 shares of employment agency J-Com Co. for 1 yen each (1 cent), instead of selling one share for the market price of 610,000 yen ($5,530), something the firm blamed on a typing error. Then problems with the Tokyo Stock Exchange’s computer system prevented the brokerage from canceling the sell order -- which cost it $345 million. Japan’s Financial Services Agency subsequently ordered Mizuho to improve its compliance and systems, as well as train staff better.

4. Why can’t computers catch these errors?

Even the best-laid plans and systems can’t account for human fallibility. Take cybersecurity. Germany’s chief financial regulator noted in March that the vast majority of computer security problems at banks are caused by “internal mishaps or mistakes or procedural problems,” rather than external forces such as criminal hackers. This has real-world consequences as regulators order banks with poor computer systems to hold more capital.

5. So how often do fat fingers strike?

Considering there are hundreds of markets around the world processing trillions of transactions at lightning speeds every day, not that often. Which is why when mistakes occur, the impact is so noticeable and embarrassing, as these examples show:

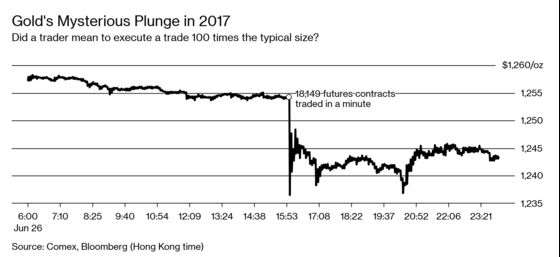

Gold’s No Haven

Gold traders were rattled in June 2017 by a huge spike in volume in New York futures when trading jumped to 1.8 million ounces of gold in just a minute, an amount bigger than the gold reserves of Finland. Gold futures fell as much as 1.6 percent. One possible explanation: A mistaken trade of 18,149 lots of a futures contract, about 100 times the size of a typical trade of 18,149 ounces.

The $617 Billion Bidder

In October 2014, someone placed more than 40 erroneous orders totaling 67.8 trillion yen on Japan’s over-the-counter market -- greater than the size of Sweden’s economy at the time. The attempted transactions included a bid to buy 57 percent of Toyota Motor Corp.’s outstanding shares and other big stakes in Japanese blue chips including Honda Motor, Canon, Sony and Nomura Holdings. The orders were canceled before they were executed.

Goldman’s Options Disruption

Confusion swept across trading desks in August 2013 as prices for equity derivatives swung without reason, with some contracts trading for $26 one minute and $1 the next. The culprit was Goldman Sachs, which experienced software errors causing it to spew unintentional orders from the first moments of trading, according to a person briefed on the matter.

UBS & Capcom

UBS Group AG said its Japanese unit mistakenly ordered 3 trillion yen of Capcom Co. convertible bonds in February 2009, almost $31 billion at the time. That was 100,000 times more than it intended, according to the bank, which cited an internal system error. The trade on the Tokyo Stock Exchange’s ToSTNeT system was canceled at no cost to UBS.

The Reference Shelf

- The aftermath of the trading frenzy in Singapore.

- Banks, not criminals, cause most IT security issues, Germany’s top regulator found.

- This trader just got his suit seeking 163 million euros ($183 million) for a fat-finger mistake from BNP Paribas thrown out.

- Bloomberg Opinion looks at the pitfalls of replacing human regulators with robot ones.

- It’s not only money: Google accidentally flooded the internet with dummy ads.

- The impoverished Central African Republic almost had a $12 billion windfall.

To contact the reporter on this story: Eric Lam in Hong Kong at elam87@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Christopher Anstey at canstey@bloomberg.net, Paul Geitner, Grant Clark

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.