Wells Fargo's Other Post-Scandal Problem: Less-Productive Staff

Wells Fargo's Other Post-Scandal Problem: Less-Productive Staff

(Bloomberg) -- Wells Fargo & Co.’s leaders have repeatedly assured the public its aggressive sales culture is gone after quotas led workers to foist unwanted products on clients. Now another problem is festering: low productivity.

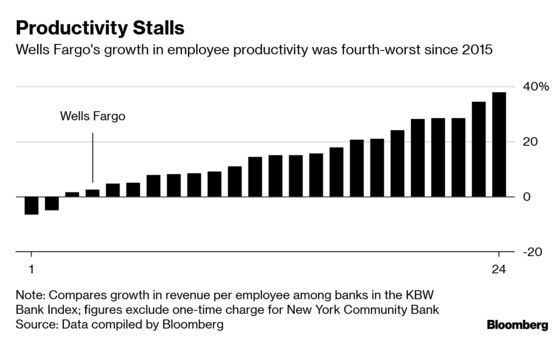

The bank, which employs more people than any other in the U.S., generated about $330,000 of net revenue per employee last year, sliding behind most major peers. By the end of last year, Wells Fargo ranked 15th among the 24 companies in the KBW Bank Index, which tracks big U.S. commercial lenders. Five regional banks have surpassed Wells Fargo by that measure since the company scrapped sales targets and incentive programs in 2016 that fueled both growth and abuses.

“I would almost guarantee that the people running it would like to improve those numbers,” said Bill Smead, chief executive officer of Smead Capital Management, which owns 1.3 million Wells Fargo shares.

The situation helps explain why Wells Fargo is working to pare its workforce of 259,000 -- enough to employ most of Alaska. CEO Tim Sloan announced plans in September to trim as many as 10 percent of jobs within three years to help meet customer needs “in a more streamlined and efficient manner.” He’s already made progress: Headcount shrank by 3,700 in 2018.

Public pressure on Wells Fargo was on full display this week as Democrats and Republicans took turns chastising Sloan at a hearing on Capitol Hill. At least five members of the House Financial Services Committee grilled Sloan on whether the firm has done enough to unwind programs that underpinned its push to sell more products.

“It’s my job as CEO to make sure things change, and they are changing,” Sloan assured lawmakers. A Wells Fargo spokesman declined to comment for this article.

In 2015, Wells Fargo ranked 10th by revenue per employee in the KBW index before its scandals began emerging the next year. The firm eliminated its old sales system, which tracked the performance of individual workers, sometimes sanctioning them for missing quotas or offering rewards to those who achieved certain targets. Now the bank rewards staff based on customer experience, customer loyalty and team performance.

By the end of last year, Wells Fargo’s revenue per employee had climbed just 2.6 percent from its pre-scandal level, slower than at its biggest competitors. At JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Bank of America Corp., that number climbed nearly 15 percent over the period, and at Citigroup Inc. it rose 8 percent.

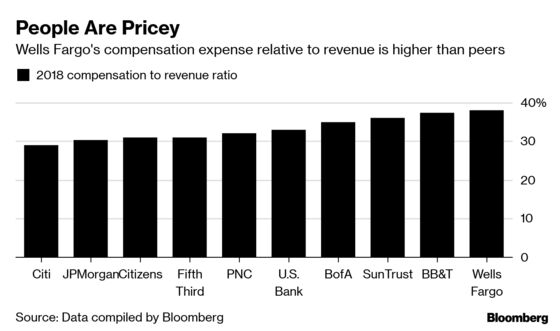

Wells Fargo’s high headcount comes at a cost. Its compensation ratio, a measure of how much the bank pays to employees as a percentage of revenue, is the highest among the 10 biggest commercial U.S. banks. Bringing down that spending could help Sloan control expenses following years of scandal-related costs.

The scandals are forcing Wells Fargo to develop new ways to motivate staff while spending more on compliance. And that means making other adjustments to sustain earnings.

“They’re trying to go from hyper-productivity, where people were more productive than what the law or company would want,” Smead said. “There’s going to be a stretch of time when you’ve cleaned the deck where people are just not going to be as aggressive.”

In past years, being the least productive bank among the titans has proven to be a harbinger of transformational change.

Bank of America ranked last by revenue per employee among the biggest four in September 2011 when it announced a plan to cut 30,000 jobs from what was then the industry’s largest workforce. It reached the target, then kept cutting as it shut branches and promoted mobile apps.

By the end of last year, the Charlotte-based lender had eliminated 84,000 jobs from a year-end peak of 288,000 in 2010. Revenue per employee rose 17 percent in that time and earnings improved. From the start of Bank of America’s job-cutting binge, its stock returned 96 percent.

“Just think about moving that many people,” CEO Brian Moynihan said of job cuts while looking back at his tenure during a CNBC interview last year. “That’s, I think, more employees than Delta has.”

Citigroup ranked as the least efficient of the four banks in October 2012. It, too, took action, paring underperforming businesses overseas.

A similar emphasis on efficiency will probably be a theme at Wells Fargo for some time.

“It’s where you are in your life cycle of repairing yourself for regulatory and profitability reasons,” veteran bank analyst Charles Peabody said in an interview. “Citi and BofA are on the improving side of that, whereas Wells is on the ramping-up costs side.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Hannah Levitt in New York at hlevitt@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Michael J. Moore at mmoore55@bloomberg.net, Dan Reichl, David Scheer

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.