Virus Shines a Light on Housing Plight of Israel’s Orthodox Jews

Virus Shines a Light on Housing Plight of Israel’s Orthodox Jews

(Bloomberg) -- Below ground level in Bnei Brak, a densely packed ultra-Orthodox Jewish city in Israel’s center, 23-year-old Eliyahu lives with his wife and daughter in a converted parking garage. There’s no sunlight or cell-phone service in their two-room apartment, and rent isn’t cheap at 3,200 shekels ($945) a month. But Eliyahu isn’t thinking of moving.

“My work is here, my wife’s work is here, friends are here, family is here,” said the events planner, who asked that his last name be withheld. “I still haven’t explored the idea of living in another place.”

With an average of seven children per woman, ultra-Orthodox Jews are Israel’s fastest growing demographic, and the cramped quarters and the close proximity in which they live have made them the country’s biggest coronavirus victims. In Bnei Brak and Jerusalem, like in New York, the lack of strict social distancing by some Orthodox Jews -- whose lives revolve around family, community gatherings and religious services -- has hit them hard.

The pandemic has starkly brought to the fore the community’s long-standing housing crisis, marked by rising prices and limited supplies. While many ultra-Orthodox Jews, concentrated in the country’s center, are reluctant to move, the virus crisis may spur a population shift that has the potential to remake Israel’s periphery.

“It could have such an effect,” said Eitan Regev, a researcher with the Israel Democracy Institute, adding that the lockdowns could already be motivating some people to move. “It’s much harder for such big families to stay locked inside such small houses.”

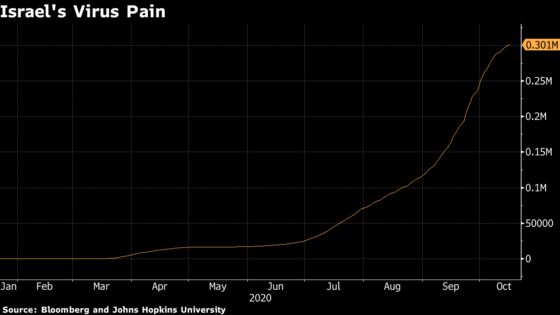

Although just 12% of Israel’s population, the Haredim, as the ultra-Orthodox are called in Hebrew, accounted for 40% of all new Covid-19 cases at the start of October. The two Haredi centers of Jerusalem and Bnei Brak have the most cases of any city in Israel, and at least twice as many as the secular Tel Aviv metropolis.

“The crowding puts them at much higher risk,” said Hagai Levine, a Hebrew University professor and chair of the Israeli Association of Public Health Physicians. “It’s not only inside the house, it’s also in the building and in the neighborhood. It’s very crowded, so you are bound to be exposed to others.”

The community is concentrated in Israel’s center because that’s where its rabbinic institutions and cultural life are. Real estate there is expensive, and the poverty of the ultra-Orthodox Jews complicates their pursuit of better housing. Half the community’s men are not in the workforce, spending their days studying religious texts, while the women work in less lucrative fields like education.

The periphery’s poor transport and job prospects and its distance from the larger community make Orthodox Jews reluctant to move. Still, the virus is making things difficult.

“Living with so many people together and everything, it’s almost impossible to control the situation,” said Nechemia Steinberger, a senior director at the nonprofit Kemach Foundation, which secures jobs for the ultra-Orthodox.

If and when parts of the community move, how that migration happens may have significant implications for Israel. Regev estimates the ultra-Orthodox will buy 200,000 apartments over the next 20 years. If purchases are mostly in existing cities with secular majorities instead of in new towns for the Haredim, that could spark social tensions, he said.

The ultra-Orthodox parties’ political clout has grown alongside their population, giving them key government ministries, like housing. Relations are strained with some secular Israelis, who object to Haredi control over issues like marriage or public transportation on the sabbath.

The Haredim have been buying property in the periphery, doubling purchases there to more than 40% over the last couple of decades. Many are investments made by young couples who want to own a house, but can’t afford the pricey center. However, as their families grow, a big migration could get underway.

“I’ve been saying for 30 years that we need to go to the periphery. Why? Because, God bless, our community is growing,” said Moshe Lebowitz, the founding mayor of an ultra-Orthodox West Bank settlement called Beitar Illit. “From the point of view of health, from the point of view of building normal institutions, it’s impossible anymore to build in the center.”

New towns exclusively for the community have been built or are in the planning stages. In the south, Lebowitz is an adviser for one such city called Kasif, which he says is in the final planning stages and could begin construction within about a year.

“There’s a need for at least another two Haredi cities in the next 10 to 20 years,” said Yitzhak Pindros, a lawmaker for the ultra-Orthodox United Torah Judaism party. “This is something that dramatically could change what is going on in Israel.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.