Escaping Venezuela

Escaping Venezuela

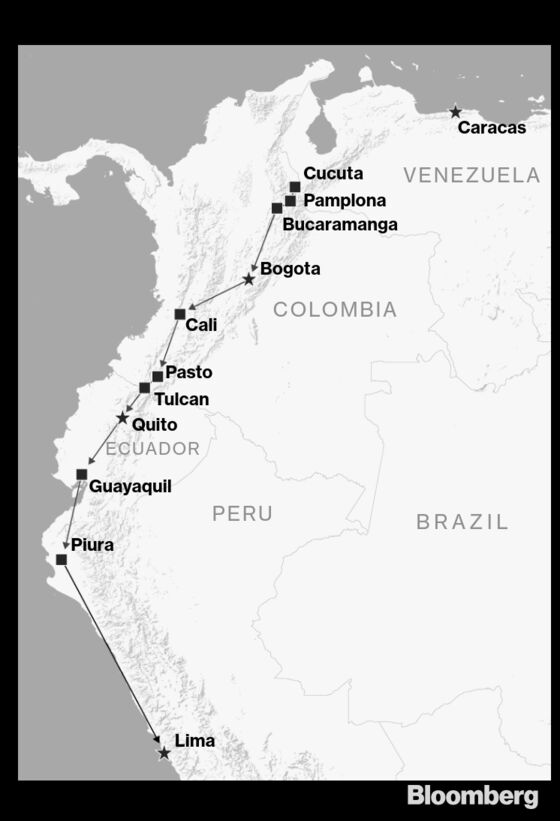

(Bloomberg) -- They’re called “los caminantes”—the walkers—the Venezuelans so poor and so desperate to flee their country’s humanitarian crisis that they set off on foot to surrounding nations in search of work. Their journey may only take them to Cucuta, the Colombian town just across the border, or as far south as Buenos Aires, some 5,000 miles from Caracas.

And while most of them manage to hitch rides for parts of the trek, they will have no choice but to hoof it for hours and, at times, days on end, through what can be brutal conditions—the bitter cold of the Andes and the searing heat of the tropical savanna. One dreaded spot alone, the Paramo de Berlin, a frigid, wind-swept highland in northern Colombia that soars some 12,000 feet into the sky, is reported to have claimed several lives.

As Nicolas Maduro, the autocratic leader of Venezuela, stymies international efforts to strangle his government and drive him out of power, one thing is clear: more and more people will choose to walk out of the country. In all, some two million are expected to migrate in 2019. We spent a couple of days with one group of them. This is their tale.

February 25, 12:00 P.M.

When traveling for days on end in the back of trucks and on foot, hygiene is a constant challenge. Any source of water is a potential bathtub. Within minutes of first spotting the group—a collection of 17 young men, women and children who banded together just before crossing into Colombia—they all headed to a nearby river to bath, brush their teeth and wash their clothes.

They were about 10 hours (measured in walking time, that is) from the Venezuelan border, just outside a tiny Colombian town called La Donjuana. First, it was the men’s turn. The sun was bright and warm and the water cool, and so they lingered there for a while and made small talk. Luis, Richard and Hector quickly emerged as the leaders of the group. When they were dried off and dressed, they headed back to the little shelter where they had been resting, and Hector’s wife, Gualesca, and the other women took their turn.

February 26, 7:30 A.M.

Rested and with their bellies full for the first time in days, the group was ready to set out on one of the roughest parts of the passage through Colombia—up and over the Paramo de Berlin. There were many smiles here early in the day. They wouldn’t last long.

The group had stumbled into one another days earlier at a bus stop in Barinas, a sweltering, sun-splashed city in the Venezuelan plains that lies a couple hundred miles from the Colombian border. Once they all realized that they had the same destination—Peru—they decided to unite and travel in a pack. They were an eclectic group: a Kimberly-Clark factory worker, a fruit vendor, an Army paratrooper, a National Guardsman, an oil roughneck, among others.

There were advantages to moving in a pack. Most importantly, there’s safety in numbers. They could help protect each other from the criminals they were bound to encounter. And for the men traveling on their own, the prospect of having young children with them was tempting. Yes, the kids would slow the group down when traveling on foot, but, they figured, the sight of their small, helpless figures would make truckers more likely to stop and offer them rides.

The journey bogged down quickly, before they even left Venezuela. As they were approaching the border, Maduro suddenly closed it. Unable to simply walk across the Simon Bolivar international bridge as millions had before them, they resorted to doling out some of the precious little cash they had to gun-toting bandits, known as “trocheros,” to escort them through backwoods controlled by drug cartels.

February 26, 9:00 A.M.

“Remove all the stones in our path, Lord... Blessed you are, Father... Please have the Holy Spirit guide us, Lord.”

After huddling to pray together, they begin the day’s trek. The first order of business was getting through the small city of Pamplona. Moving on foot, the group tired quickly. The town is set high up in the Andes—well over 8,000 feet above sea level—and seemingly all its streets go either straight up or straight down.

Even for the well-nourished and physically fit, hiking through it would be taxing. For hungry migrants, lugging unwieldy suitcases and toting babies, it can be excruciating. And dangerous. Just minutes into their journey, frantic shrieks rang out. Hector and Richard turned around to find a young woman passed out on the ground as her traveling companion helplessly looked on.

They ran over. The unconscious woman was gaunt, her skin pale. They tried to revive her, but she was unresponsive. Luckily, though, a doctor happened to be nearby. She heard the commotion and rushed over on a motorcycle to whisk the woman and her companion away.

February 26, 2:00 P.M.

As they approached the Paramo de Berlin, tensions began to flare. The plan was for the women to take a bus over the mountain with the children while the men set out on foot. As they waited for the bus, the women purchased some food and then, worried about the rapidly dropping temperatures, bought hats and gloves for the kids. The men got angry. The hats and gloves were a waste of money, they grumbled, and they were hungry too. “Men aren’t made of steel,’’ Richard barked out at one point. He and some of the other men talked about splitting from the group as they began the climb.

February 26, 4:00 P.M.

The hike through the Paramo took the biggest toll on Luis. He lost his breath quickly and stopped frequently, much to the frustration of the others. He had respiratory issues, he said, the result of a damaged lung and a bad case of asthma.

Luis was a polarizing figure in the group almost from the outset. He splurged on cigarettes, draining the group’s cash, and, according to the others, would smoke marijuana at night, sometimes in front of the kids.

But he knew the route, having made the trip to Peru before, and he had the scars to show it. Upon returning to Venezuela weeks earlier to meet up with family, he said he was mugged by three men, who took his valuables—a Huawei phone and $250 in cash—and then whacked him with a machete. The blow was aimed at his neck, he said, but he managed to block the machete with his forearm and escape. The attack left him with a deep, nasty wound just above his left wrist. He fretted about it and poked at it a lot and when he did, it oozed pus and blood.

February 26, 7:00 P.M.

The outbreaks of xenophobia toward Venezuelan migrants get most of the attention in South America nowadays, but they overshadow acts of kindness, big and small, that are seen every hour of every day. In the course of 48 hours, the group of 17 received shelter, food, travel tips and, perhaps most importantly, rides from several truckers, including one who scooped the men up at their most vulnerable moment—as they were crossing the Paramo. It was freezing in the back of the uncovered truck and they had to huddle in pairs for warmth, but the ride cut hours off their trip and reunited them with the women shortly after nightfall.

Epilogue

March 4

Six days later, we reconnected with the group. They were several hundred miles to the south, walking on the highway through the rolling, green hills just north of the Ecuadorean border. Despite the tension and quarrels, they were all together—all, that is, except Luis. They had parted ways with him days earlier and hadn't seen him since.

March 10

In Peru, at last. Most of the group, including Hector, Gualesca and their two kids, ended their journey in Piura, a small city wedged in the strip of desert between the Andes and the Pacific Ocean. When they arrived, they had no concrete plans on how to make a living.

Richard and his cousin, Antony, carried on further south until they made it to a town in the mountains that ring the capital city of Lima. Richard's sister already lived there and took the two men in. A welder by trade who labored for years in Venezuela's oil industry, Richard found work immediately in a mechanic's shop. Antony had less luck initially and kept himself busy selling candy and cleaning windshields until, after a few days, Richard managed to score him a job too.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: David Papadopoulos at papadopoulos@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.