(Bloomberg Opinion) -- A year ago, I sat with Vale SA’s then-Chief Executive Officer Fabio Schvartsman in Davos, sipping lukewarm coffee. He chatted amiably about the next stage of the turnaround at the Brazilian mining giant, unaware that within 24 hours a river of sludge from one of his dams would take 270 lives in the town of Brumadinho. This week, he was among executives and former employees charged with homicide.

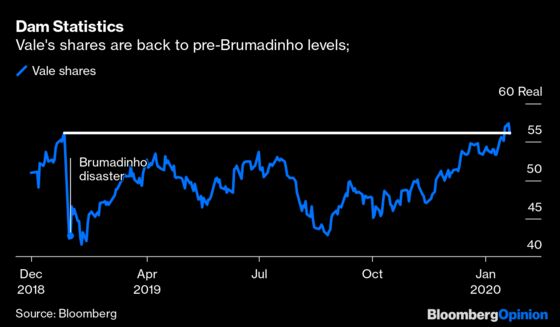

The disaster on Jan. 25, 2019, a human and environmental catastrophe that’s been compared with BP Plc’s Deepwater Horizon oil spill, was supposed to be a moment of reckoning. It was, after all, Vale’s second such accident in just over three years. Yet 12 months on, shares in the $70 billion group are back at pre-Brumadinho levels, pointing to something less dramatic. The rebound also suggests investors are struggling to grasp the painful longer-term costs of such accidents for the company and the industry, in the era of stakeholder capitalism.

The dam at the Corrego do Feijao mine was a problem from the beginning. It dated back to 1976, when it was started by a company later acquired by Vale. The dam was built over decades, using the tailings, or mining waste. New layers were added on top of old ones, until 2013. Unfortunately, such dams require water to drain out if they are to remain stable; the technical investigation found this one was too steep, and allowed to get too wet. High iron content made it brittle, too.

In the end, there was no warning. After heavy rainfall in late 2018, it simply collapsed, releasing 10 million cubic meters of mud – roughly 4,000 Olympic swimming pools – in under five minutes.

The timing for Vale was painful. It found itself accused of negligence and worse, just as the miner was emerging from another accident, the 2015 collapse of a dam owned by Samarco Mineracao SA, its joint venture with BHP Group. Schvartsman, a former pulp and paper executive, had stepped into the top job in 2017 vowing “never again.”

The market’s immediate reaction was strong. Vale lost nearly a quarter of its value, almost $20 billion. Investors’ calculations of the ultimate cost were then obscured, though, as the hit to supply at the world’s largest iron-ore exporter eventually drove prices of the steelmaking ingredient well above $100 per metric ton.

The cost is still unclear. That shouldn’t be startling. BP was still raising estimates for outstanding claims for Deepwater Horizon years after the event. In the end, the British oil major sold more than $70 billion of assets to remain in business; its shares haven’t recovered.

The scale and jurisdiction are different here. Still, it’s surprising that Vale’s shares have bounced back.

That doesn’t mean that no costs have been priced in. Compare Vale with iron ore-focused rival Rio Tinto Group. Rio’s London shares have risen almost 18% in the past 12 months thanks to surging iron-ore prices. Add in the impact of reinvested dividends, and the total return is more than 30%. The share increase alone implies a gap of some $16 billion with Vale.

Some of that sum reflects the impact of lost revenue, given the 93-million-ton hit to production during a year when the price of high-quality Brazilian iron ore fines delivered to northern China averaged more than $100 a ton.

The remainder, though, isn’t too far from what Vale itself has already set aside, handed out or had frozen for potential liabilities from Brumadinho: It paid $1.6 billion for reparations and compensation in 2019, and has provisioned $5.4 billion. Some 7.5 billion Brazilian real ($1.8 billion) of assets are frozen by the courts.

The trouble is, that covers mostly first-order costs, like payouts for workers and families, the wider clean-up and some fixes to similar facilities elsewhere. Vale plans to spend $1.8 billion over five years shifting to dry stacking, a safer method to dispose of mine waste. By 2023, it says 70% of its production will use this.

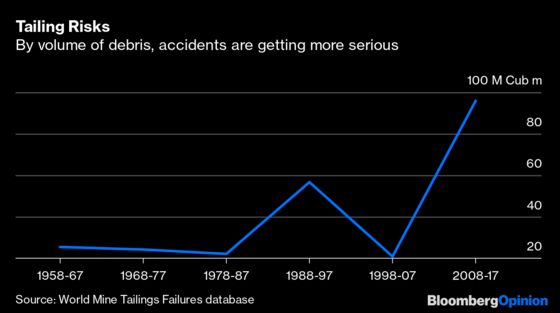

The wider impact of Brumadinho and the 2015 disaster on Vale and the industry will be more profound. Risks to tailings dams and other mining installations are already increasing, and there may be more monitoring in some corners. Extreme weather including heavy rainfall is far more frequent, and declining ore grades, or the percentage of minerals in rock that’s dug up, mean more waste to deal with. This coincides with increased concern among shareholders for the environmental impact of investments.

Higher bills for more inspections might be manageable for large miners, but what about significantly slower permits, higher costs of closure, or projects that get blocked entirely by disgruntled communities? During a high tide for populism in Brazil and elsewhere, that’s harder than ever to estimate. It’s unlikely Brumadinho will be forgotten by governments and communities as disasters like Mount Polley in 2014 largely were.

According to a report by the Church of England Pensions Board, 40 of the top 50 mining companies had made disclosures on their websites about tailings dams as of late December, as requested by campaigners and shareholders. That’s a solid three-quarters of the mining industry by market capitalization, but leaves plenty of laggards. Schvartsman, in the aftermath of Brumadinho, said Vale was a “Brazilian jewel” that could not be condemned because of an accident. His gross underestimation of the seriousness of the situation cost him his job, and moreInvestors and rivals would be wise not to make the same mistake.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Matthew Brooker at mbrooker1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Clara Ferreira Marques is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities and environmental, social and governance issues. Previously, she was an associate editor for Reuters Breakingviews, and editor and correspondent for Reuters in Singapore, India, the U.K., Italy and Russia.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.