Poland Is Welcoming Ukrainian Refugees, But It’s Taking a Toll

Ukraine War Effort Rebrands Poland, But Takes Toll on Nation

(Bloomberg) -- It’s been a month since the war in Ukraine started, and the flow of refugees arriving at Warsaw’s biggest railway station shows no sign of abating. Crowds of people disembark trains from the border and wait for shuttle buses to temporary shelters at exhibition and sports venues. Outside, passersby are asked for directions.

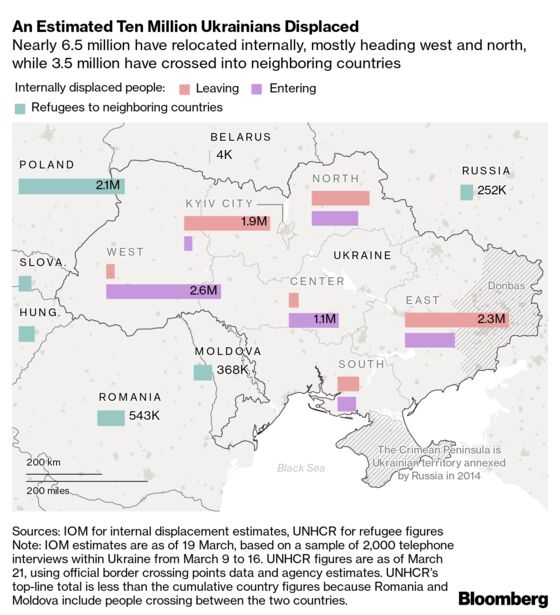

The unflinching support for their neighbors — at least 2.1 million of them and counting — has turned into a pivotal moment for Poles, but it’s also now raising some urgent questions over what happens next, politically and economically.

Poland is winning international kudos for its response to the humanitarian impact. The war effort is transforming the country into a European leader from the rogue whose populist government has been locked in a bitter dispute with Brussels over rule of law and which has also strained relations with the U.S. in recent years. Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki declared on March 19 that Poland “never had such an excellent brand all over the world.” U.S. President Joe Biden is due to visit this week.

Yet the unprecedented increase in numbers is stretching resources across a country more used to being a net exporter of people than a haven for incomers. The population of Poland’s capital city alone has swelled by about 20% — some 300,000 people — in four weeks and accommodation is running out. “Every day is somehow a new start with the risk that supplies or other help may dry up,” said Marcin, a 22-year-old Polish student in an orange vest volunteering at an improvised canteen at the station.

Rental costs in major cities have soared as much as 30% in the past two weeks, according to PKO Bank Polski SA, as the availability of apartments roughly halved. That’s as Poland, like so many other places, is trying to cope with inflation at a 20-year high, and soaring food and energy bills.

Some refugees will fill gaps in Poland’s labor market. Half of vacant jobs, though, are in the male-dominated construction sector and most of the Ukrainian arrivals are women, the elderly and children who need places in schools and kindergartens. And at least 150,000 Ukrainian men went the other way, going home to fight.

Amnesty International warned the Polish authorities must do more to reduce the burden on volunteers and households that have opened their doors. After a 10-day visit to the Ukraine border, the organization called the situation in Poland “chaotic and dangerous.”

“This is an exceptional moment for Poles to be seen as a great nation by the whole world,” said Beata Laciak, sociology professor and member of the board at the Public Affairs Institute in Warsaw. “But this work is not a sprint, it’s going to be marathon. The question is: can the government help Poles run long enough, so at the end of the marathon we could call it the best moment for Poland this century.”

Poland is likely to remain the destination of choice for Ukrainians even if there’s a pan-European agreement to share the work of providing refuge. The country of about 38 million until last month was already home to roughly 1 million Ukrainians arriving in the wake of the separatist conflict in the east that started in 2014. That compares with more than 2 million Poles who left to work abroad since their country joined the European Union a decade earlier.

Other Ukrainian neighbors such as Hungary and Romania have also embraced those fleeing Russian President Vladimir Putin’s forces, yet the numbers are dwarfed by Poland’s influx.

The response in Poland is in stark contrast to the Law & Justice government’s opposition — along with Hungary — to mainly Muslim refugees from places like Syria during the 2015 crisis that caused a rift within the EU. Poland can take care of Ukrainians because it’s “a strong, proud nation,” according to the prime minister.

But critics say they are mainly helped by ordinary Poles, non-governmental groups and municipalities. The government estimates that the cost of helping refugees, excluding education and healthcare, will total 2.2 billion euros ($2.4 billion) this year alone and is calling on the EU to provide more money.

So far, Poland has set aside 8 billion zloty ($1.7 billion) to help refugees find work, gain access to schools and healthcare and pay those who host them in their homes. The aid equates to 40 zloty per refugee a day, the government said. That’s not enough to cover the costs, according to Ala Gwardyan, who is among the phalanx of Poles who have offered shelter to Ukrainians.

“Poles are helping and Ukrainians are grateful, but Poles will soon get burned out,” she said. “We need to help them to be free in Poland and not to make them dependent on us and our aid.”

Moved by the images of lines of people building up on the border, she opened up her 42 square-meter (452 square-foot) apartment to a mother, her four-year-old son plus the woman’s sister. Gwardyan, 40, from the city of Lodz about 120 kilometers (75 miles) from Warsaw, is taking time off work to help her new housemates deal with various public institutions and medical centers to get them established in Poland.

She’s calling on the government and European allies to do more to ensure the national showing of “love won’t turn into infatuation only — or something even worse.” The new law allowing refugees to settle “is in fact still keeping the main burden on Poles,” she said.

Civic and corporate Poland has responded. In Warsaw, the engine of the economy, schools, kindergartens and job centers are popping up to help Ukrainians establish a future in the country.

One example is the commercial sector, which includes such industries as hospitality and retail. It has over 15,000 vacant jobs to fill, according to Andrzej Kubisiak, the deputy director of the Polish Economic Institute. Convenience store chain Zabka and supermarket operator Biedronka have created special hiring platforms, as have some beauty salons and restaurants.

There could be relatively quick job offers coming from tourism and seasonal work in agriculture, plus there are holes in health care and education, said Kubisiak. But the problem is that more broadly there’s a “structural mismatch” between the people Poland is now absorbing and the economy, he said. “These are not economic refugees, these people are running away, they are fleeing the war,” said Kubisiak. “So stop thinking about them as we use to think about Ukrainians who used to come to Poland before the war.”

Meanwhile, Law & Justice has also improved its popularity shaken by years of political bickering and the row with the EU. The party is now supported by 33% of voters, up from 31% four months ago. Poland’s response “puts us in the right position in international politics,” Morawiecki said on March 19. The country is breaking through what “previously was this wall of unfair isolation,” he said.

The dispute with the EU over rule of law and, in particular, Poland’s treatment of its judiciary has effectively been dropped, even if Brussels is still fining the country 1 million euros a day on paper following a European Court of Justice ruling in October. A freeze of some 36 billion euros in the EU’s post-pandemic aid aimed for Poland may soon be lifted.

Yet how the war unfolds for Ukraine’s biggest western neighbor will likely depend on how the government can help its citizens cope with the cost of providing a haven. From sleeping bags to soup kitchens to ad hoc transfers and opened homes, Poles are continuing to reach out to help.

One issue is that Ukrainians need a Polish social security number to use public services, including access to healthcare and education. Gwardyan’s guests stood in the line from 6 a.m. to receive the number 1,760, meaning it will arrive in three weeks, she said. The money to cover the cost a of Ukrainian’s stay is paid in 30 days from the application date.

At Warsaw Central, large white tents together with portable toilets adjacent to the station’s main hall are now in stark contrast to the glass skyscrapers of the Polish capital. Volunteers wearing yellow vests distribute food, hygienic products and SIM cards. On Wednesday, a fresh group of helpers is getting trained up. They soon will handle requests for longer-term accommodation.

But the biggest issue is a lack of clarity as to how long the crisis may last. “We are here to help, but most experienced guys are getting tired and some already need to return to their regular workplaces,” said Marcin, the student. “The authorities aren’t also giving us any guidance what the final plan is for places such as the station.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.