UBS Wealth Bankers Get Dose of Credit Suisse Tonic in Khan Plan

As Christmas approached in Zurich, UBS Group AG’s private bankers were bracing for their own winter storm.

(Bloomberg) -- As Christmas approached in Zurich, UBS Group AG’s private bankers were bracing for their own winter storm.

The deadline had passed for a 60-day review of the bank’s wealth-management business -- the world’s biggest -- by its new co-head, Iqbal Khan. Many were anxious about the future of a unit that had lost its edge. Some stayed in their offices until the last moments before the holiday, fearing they might not have jobs in January, according to people familiar with the matter.

When Khan broke his silence Jan. 7, he triggered the biggest shakeup in wealth management since Chief Executive Officer Sergio Ermotti made it the centerpiece of his strategy almost a decade earlier. Key units were reorganized or dismantled, potential rivals were weakened and 500 jobs, from managing director on down, were eliminated.

“Khan has to make his mark now,” said Andreas Venditti, an analyst at Vontobel. “He wants the results he achieves to be epic.”

While the job losses are smaller than at many competitors -- Deutsche Bank AG is culling 18,000 positions -- it’s the first time in years that UBS’s private bankers have felt the heat. For a decade, they’d driven growth as Ermotti pivoted UBS away from investment banking and toward the business of managing money for the rich. The strategy worked well after the financial crisis, when ultra-low interest rates fueled a wave of wealth creation around the world.

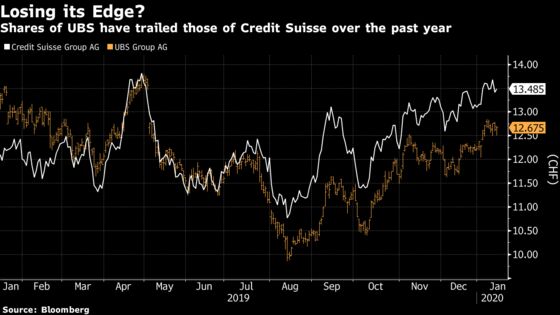

But the rise of passive investing has changed the landscape, upending the economics of wealth management. Rivals such as Credit Suisse Group AG, where Khan worked until his controversial departure in mid-2019, were steadily catching up. UBS shareholders and employees had grown uneasy that management seemed slow to react, according to conversations with insiders who asked to remain anonymous.

Shares of UBS were little changed last year, trailing the 21% gain by Credit Suisse. They’ve risen about 3% since the reorganization of wealth management was announced last week.

UBS declined to comment for this story.

Ermotti, seeking to appease investors, tasked Khan and his co-head Tom Naratil with a plan to revive the wealth unit, UBS’s most important business. The tight deadline offered an ambitious Khan the opportunity for radical action -- and an early opportunity to show that he’s future CEO material.

Kaufleuten Party

Khan was a key driver of the rebound by Credit Suisse, and his ambition was said to have played a role in his falling out with that bank’s CEO, Tidjane Thiam. After joining UBS in October, following an interlude dominated by a spying scandal, he identified “quick wins” by increasing lending to the rich.

Much of what Khan is proposing now follows his playbook at Credit Suisse: He’s trying to increase lending by speeding up decision-making, and wants to reduce costs by cutting red tape and moving customers who don’t need complex services to cheaper models.

Within UBS, Khan’s arrival had an instant impact. People who attended the wealth-management division’s year-end party at Zurich’s storied Kaufleuten Club say the mood was lighter than in previous years, when the event was overshadowed by a stock market correction and the shock departure of Juerg Zeltner, an earlier head of wealth management.

Confident Khan

Colleagues say the Pakistan-born executive is enthusiastic, energetic and talented. Former associates have described him as confident, even overly so. That said, he knows the business from several angles: Khan was a UBS auditor at Ernst & Young and a key competitor at Credit Suisse.

He’s also, at age 44, of a different generation than either Ermotti or Martin Blessing, Khan’s immediate predecessor, who was perceived as bureaucratic. In town hall meetings, Khan will highlight top performers while pointing out what hasn’t gone well. He told his risk and structuring teams that he wants to see at least two deals a week on his desk. That attitude has rubbed off: One executive said he’d call Khan if another manager didn’t help organize a loan for a client within two days.

Some UBS veterans were stunned by the speed and scale of the overhaul. Others welcomed it unreservedly. The bank had done well since its last reinvention in 2012, but as evolving markets demanded change, there was a sense of inertia: The wrong lever might be pulled, damaging the model.

Reversing Course

Ermotti did make some changes, merging UBS’s wealth-management operations into a single unit with $2.5 trillion under management to tap economies of scale. The move produced savings but failed to kickstart growth and fell flat with investors. Khan is now reversing course, devolving power to regional operations.

Earlier last year, UBS even considered a deal with Deutsche Bank -- first a merger of their asset management units, then a wholesale combination. Those talks eventually fell apart.

For now, Khan’s arrival has taken pressure off the CEO to come up with a bigger strategic overhaul. The new man has dismantled the ultra-high net worth business led by Josef Stadler, as well as a miniature investment bank within the wealth unit that was seen as a drag on loan approvals and a source of costs. He also split up the business serving Europe, the Middle East and Africa.

First Step

“On the surface the changes don’t seem quite big, and there are some similarities with what he did at Credit Suisse,” said Venditti at Vontobel. “But the more you read the details, this is a big change, especially for UBS. They’ve underplayed the changes because top management has kept saying that everything is fine.”

The resulting job cuts represent less than 1% of UBS’s workforce. But for private bankers unaccustomed to the sort of turnover seen at the investment bank, they’re a reminder that the comfortable times are over.

Now Khan will need to execute on the restructuring while bringing in more of those quick wins and ensuring that faster loan approvals don’t bring greater risk. And at a time of intense competition for private bankers and their clients, he must make sure both stay on board.

“Khan has some time to prove himself, and the best way to prove himself is to bring results,” said Venditti. “Then he can certainly better position himself to be the next CEO.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Patrick Winters in Zurich at pwinters3@bloomberg.net;Marion Halftermeyer in Zurich at mhalftermeye@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Dale Crofts at dcrofts@bloomberg.net, Christian Baumgaertel, Paul Sillitoe

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.