U.S. Schools Race to Spend $122 Billion of Rescue Aid in Time Crunch

U.S. Schools Race to Spend $122 Billion of Rescue Aid in Time Crunch

(Bloomberg) -- U.S. school districts are racing to figure out how to spend $122 billion of American Rescue Plan stimulus money before a September 2024 deadline, and some districts want more time to distribute the aid.

Spending money might seem easy, but it’s not. Schools need to budget their funds carefully and by law have to consult with various stakeholders before committing to projects. On top of that, contractors and materials have been hard to come by during the pandemic.

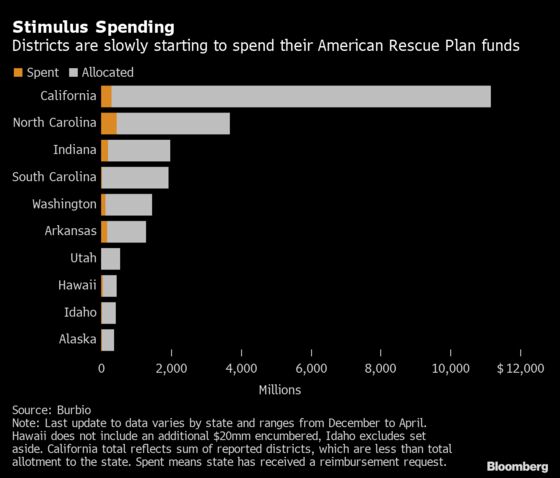

In a sampling of 10 states, schools had only gone through between 0.5% and 15% of their allocated funds in the year after the money was made available, according to figures compiled by Burbio, a Pelham, New York-based company that tracks school data. Some school groups have asked the Department of Education to extend the deadline.

“I’m talking to districts nonstop. The most common question I get is what should we do if we don’t spend it all?,” said Marguerite Roza, professor and director of the Edunomics Lab at Georgetown University. “Expenditure numbers suggest many districts are behind where they should have been.”

Roza estimates schools nationally need to spend roughly $4 billion monthly to finish using all the tranches from the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund, the rescue aid known as ESSER, by their respective deadlines. In January, schools spent about $2.5 billion, potentially back-loading the spending pipeline, according to her analysis. As of Jan. 31, districts had spent just under 5% of ESSER III dollars, according to Roza’s tally of the data. Still, she’s confident districts will be able to deplete their funds.

Schools have been trying to dole out vast sums in the midst of reopening buildings and navigating case spikes. Time to vet proposals, conduct research, find vendors, secure approvals and hire in a tight labor market all contribute to the sluggish pace. Plus under the rules, states and school districts are required to work with community members like students, parents and other stakeholders to develop spending plans.

The pace reflects the nature of school budgeting and spending, and doesn’t necessarily mean schools are dragging their feet, said Ralph Martire, executive director of the Center for Tax and Budget Accountability. “I’m not surprised that there is a significant lag between understanding how much ESSER support you’re going to get, and your capacity to spend the money,” Martire said. “There are going to be some rational delays.”

The American Rescue Plan Act, passed in March 2021, included the largest ever one-time pile of cash from the federal government to help schools address the Covid-19 pandemic and followed two previous infusions of billions of dollars in federal aid for education. The law required schools to spend at least 20% of their allocated funds to address learning loss by catching students up academically. Aside from that, schools had broad flexibility to decide how best to use their money.

Extension Request

The School Superintendents Association in January sent a letter to Education Secretary Miguel Cardona asking for an extension of the ESSER III deadline through December 2026. Superintendents had expected funding for facilities from the Build Back Better Act or the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act that never materialized. And now, trying to use ARP funding for facilities ahead of the current deadline would be “nearly impossible” because of limited contractor availability and supply chain disruptions, according to the group. Kelly Leon, a spokesperson for the Department of Education, didn’t have an immediate comment.

The New York City Department of Education received about $7 billion between the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act and ARPA, and planned to spend about $3 billion in fiscal year 2022, which ends June 30. As of the first week March, the nation’s largest district had spent less than half that amount, mostly on reopening expenses, according to a report from the city’s comptroller. Pandemic-related delays, hiring difficulties, and supply chain issues are partly responsible, as well as long contracting and procurement processes, the report said.

NYC’s education department said the report mis-characterized the agency’s spending, in part because the spending data does not encompass the full year. “This funding continues to be available to the Department of Education beyond this year, and we are evaluating ways to utilize any unspent funds to continue supporting students and schools going forward,” said First Deputy Chancellor Dan Weisberg.

Slow Rollout

It’s wise to spend the money slowly, said Kelsey Bailey, chief deputy of finance for the Little Rock School District in Arkansas, which received about $64 million from ESSER III, the largest sum in the state. The district has spent $7 million and obligated another $11 million, which is more than a quarter of its funds.

School officials are still trying to understand the enormity of students’ learning loss, Bailey said. Test scores from this school year will shed light on how much catching-up students still need, but he’s confident the district will be able to spend it all.

“These funds have quite a bit of flexibility,” Bailey said. “You don’t really know all the needs of the pandemic, and I would caution districts who spend it hurriedly right now.”

Other districts have earmarked nearly all their money, but are slow to actually spend it. In South Bend, Indiana, the district has spent about 29% of their $59 million, but earmarked nearly all of it.

Kareemah Fowler, assistant superintendent of business and finance, said the district amended its plan several times to adapt to changing needs as the pandemic evolved. “A lot of districts didn’t have capacity to do all the things to get the money spent,” she said.

Variant Costs

Some districts anticipate needing more money in the event of another variant. Seattle Public Schools originally budgeted $12 million to spend on Covid precautions, but the Delta variant drove costs up to $38 million, said JoLynn Berge, the district’s assistant superintendent for business and finance.

The district received about $93 million from ESSER III. They’ve spent just over half and earmarked the rest on things like new curriculums, outdoor learning, and special education recovery services. Seattle schools also used some ESSER II funds to backfill a $30 million hole in the budget caused by shrinking enrollment in the 2019-2020 school year.

“At the end of the day, I think most school districts are happy to have this money, and are trying to be smart for using it for one-time investments,” Martire said.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.