Hunger Stunts Growth of American Babies as Inflation Hits Hard

U.S. Kids Go Hungry as Safety Net Ebbs and Inflation Soars

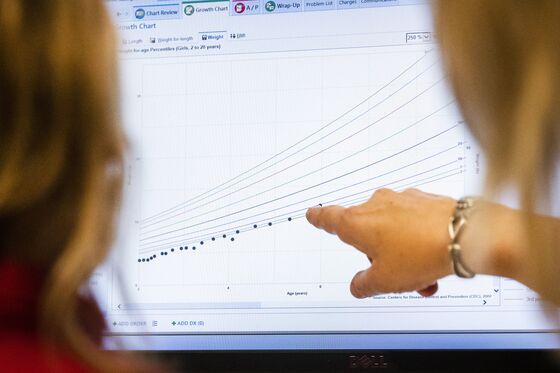

(Bloomberg) -- One-year-olds are falling further behind the growth curve at a Boston clinic that treats toddlers so underweight their brain development is at risk. In Denver, children are struggling with dental problems and obesity as families turn to cheaper, high-calorie food. And in Little Rock, Arkansas, more kids are dealing with depression and suicidal thoughts—some as young as 11—as patient charts increasingly display images of bright red wheels, used to indicate food insecurity at home.

It’s a startling turn of events: Kids in the world’s biggest economy are so seized by hunger and malnourishment that safety-net clinics treating the nation’s poorest are sounding the alarm as pandemic-relief programs run out.

“We’re the front-line window into how policies play out in the bodies of babies,” said Megan Sandel, a doctor and co-director at Boston Medical Center’s Grow Clinic, which specializes in treating kids that are severely underweight. Caseloads there are up 40% since the start of the pandemic.

“We’re just seeing an extremity of kids who are malnourished and underweight,” Sandel said.

Some of the most gripping images early in the pandemic were the lines snaking for blocks around food banks as millions of Americans were thrown out of work, many facing food insecurity for the first time in their lives. Federal programs like extended unemployment benefits and stimulus checks helped ease some of the need in the spring and summer. But now, the end of that extra aid, along with the impact from inflation, means hunger is back on the rise.

Food banks across the country are reporting a swell in demand, some even saying the need is near peak levels seen in mid-2020. Meanwhile, surging grocery costs are driving an attack on all sides: making food less affordable for both lower-income families and the food banks and pantries that serve them. Things have gotten to the level where even New York Federal Reserve President John Williams last month raised concerns over the impact rising food and transportation costs are having on families’ ability to get enough to eat.

“We’re very concerned,” said Katie Fitzgerald, chief operating officer for Feeding America, a network of 200 non-profit local and regional food banks. Without investments into emergency programs, the group is expecting a 30% drop in its available food supplies as donations dwindle and inflation hits, she said. Food banks with Feeding America in 2020 distributed a record 6.1 billion meals, almost triple the figure from 2009.

“As you head into the winter months in this country, as people have greater utility expenses for heating their homes, it tends to be a time when we see increased food insecurity in general,” Fitzgerald said.

At the Boston clinic, one-year-olds have been coming in at the size of a normal six-month-old, Sandel said. At least a fifth of the clinic’s children have been falling further behind in recent months.

“And we’re getting new cases that are much more severe than we’re used to getting,” Sandel said.

Inflation is the latest driver of increasing hunger across the world, after the pandemic’s economic blow meant that as many as 811 million people—about a 10th of the global population—were undernourished in 2020, according to the United Nations. In countries like Brazil, poverty has come roaring back after emergency aid ran out, and the U.N.’s gauge of food prices has surged more than 20% this year.

In the U.S., data from the Census Bureau show food insecurity started trending higher in late August through October, when the survey was suspended. Data collection resumed this month. When those figures publish, it’s likely to show the situation has grown even worse as higher prices for everything from gasoline to housing cut into what people have left to spend on food.

“Food insecurity is becoming more widespread—and more difficult to resolve.” Williams of the New York Fed said in a Nov. 30 speech. “The ripple effects expand across the economy, as food insecurity drives economic inequality, which in turn is a barrier to cultivating a healthy workforce.”

Margaret Tomcho, a doctor and medical director at Denver Health's Westside Family Health Center, said that more families are shifting to inexpensive junk food since they can’t afford to eat as many fresh fruits and vegetables. The clinic also regularly sees children with anemia because of inadequate diets, which will have an impact on brain development, she said.

“We’re going to see the results years down the road,” she said, adding that disparities are also sharpening between White Americans and people of color, immigrants and refugees, who are more likely to experience food insecurity.

Many of the Spanish-speaking immigrants pediatrician Eduardo Ochoa sees haven’t applied for government aid, sometimes because of language barriers and sometimes because they are either undocumented or wary that public assistance might undermine their legal immigration status, he said. At the Arkansas Children’s Hospital’s Southwest Little Rock Clinic, medical charts he sees increasingly show families flagged as food insecure based on a parent’s answers to a screening questionnaire. Mental-health issues have also grown “more acute,” he said.

“It seems like there is a higher proportion of kids admitting to suicide risk than before the pandemic,” he said. “And we’re seeing younger age kids admitting to that—11 or 12 years, rather than high-school children.”

Even before the pandemic, the U.S. already had the highest number of people who couldn’t afford a basic energy-efficient diet among the world’s 63 high-income countries. And now, the rising cost of food will mean even more hardship. In 2020, the poorest fifth of households spent 27% of their income on food, compared with 7% for the highest earners, according to U.S. government data.

The impact isn’t limited to just the poorest families.

Jean Rykaczewski, executive director of West Alabama Food Bank, said her program is seeing demand from a lot of lower middle-class working families, people with children living paycheck-to-paycheck on $30,000 to $40,000 per year.

Some who come to the food bank have had to take unpaid time off to care for children who have been exposed to Covid in the classroom and must remain home for 10-day quarantines. Others are unable to keep up with increasing food and gasoline prices, she said.

Grocery prices in November were up 6.4% from a year earlier, according to the Labor Department. The national average retail gas price has jumped more than 50% over the past year, reaching $3.32 per gallon as of Dec. 14.

“Any money that people saved, they went through,” Rykaczewski said. “The money has run out. Now with all the costs going up, it affects them as well.”

Omaha’s Food Bank for the Heartland is still seeing a significant increase in the numbers of people seeking assistance despite lower unemployment rates, Chief Executive Officer Brian Barks said. At the same time, food costs for the non-profit have gone up about 12% this year, hindering its ability to secure enough supplies to meet the rising demand.

Barks said he expects hunger levels will continue to stay higher for the next several years, mirroring the trajectory of the Great Recession. It took about a decade for families to recover then—the portion of Americans without enough to eat didn’t drop back to pre-recession levels until 2018, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. And just as people were starting to bounce back, they were hit again by the pandemic.

“The bottom line is that there are still people out there that continue to hurt and struggle to put food on the table,” Barks said.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.