How the U.S. and Mexican Economies Are Intertwined: By the Numbers

How the U.S. and Mexican Economies Are Intertwined: By the Numbers

(Bloomberg) -- In brandishing U.S. tariffs on Mexican imports, a surprise move that sent global financial markets into a tizzy Friday, President Donald Trump is taking aim at yet another ally and key trading partner.

The two nation’s economies have been mutually supportive for more than two decades, helped by the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1994, according to a March report from the Congressional Research Service, an analytical arm of the U.S. legislature.

The result is an intertwining of interests through trade in goods and supply chains, especially in the auto industry.

“The consequences for Mexico will be negative and severe,” said Tom Orlik, chief economist at Bloomberg Economics, of the tariff threat. “The U.S. is less prepared to fight a multi-front trade war than the rosy first-quarter gross domestic product numbers suggest.”

Here’s a snapshot of the nations’ increasing interdependence over the last quarter-century, and what’s at stake in a trade war across the border.

Overall Trade

U.S. exports to Mexico rose to $265 billion last year, from $41.6 billion in 1993. Broken down by product, shipments heading south look like this: petroleum and coal products (11%), auto parts (8%), computer equipment (7%), semiconductors and other electronic components (5%), and basic chemicals (4%).

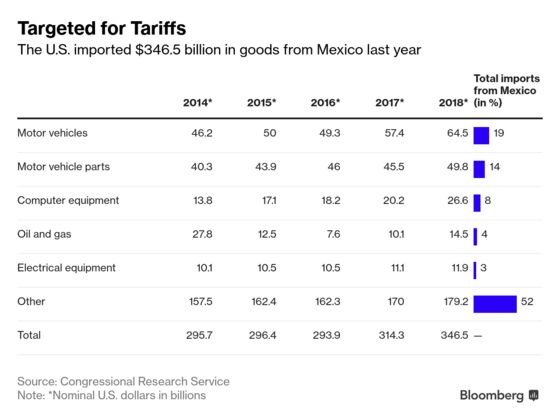

Since Nafta, U.S. imports from Mexico rose even more, to $346.5 billion last year from $39.9 billion in 1993. Here are the main imports: motor vehicles (19%), motor-vehicle parts (14%), computer equipment (8%), oil and gas (4%), and electrical equipment (3%).

While the U.S. trade deficit with Mexico was almost $82 billion in 2018, American has a trade surplus with Mexico in services.

Looking into the numbers, there’s even more at stake: About two-thirds of all U.S. imports from Mexico is related to trading within a company. This is because American manufacturers have significant production south of the border, said Torsten Slok, chief international economist at Deutsche Bank AG. If the duties are implemented “it will be a serious downside risk to the U.S. economy,” he said.

Who Pays

“This is really going to hurt American businesses who use Mexico to reduce their costs and stay competitive,” said Mary Lovely, an economics professor at Syracuse University.

As for American consumers, Chua Hak Bin, an economist at Maybank Kim Eng Research Ltd., said they “will bear an increasing proportion of the cost from tariff hikes as the coverage spreads to consumer goods.”

Investment

The U.S. is Mexico’s largest source of foreign direct investment, according to the Congressional Research Service. American FDI reached a high of $110 billion in 2017, compared with $17 billion in 1994. While the flow of investment in the other direction is much lower, it’s jumped from $2.1 billion during the first year of Nafta to $18 billion in 2017.

Remittances

In addition to investment and tourism, payments sent home from friends and family living abroad are one of the three highest sources of foreign currency for Mexico, and most of those transfers come from workers in the U.S. Record remittances to Mexico were set in 2017, with a total of $28.8 billion, up 7.5% from 2016.

Read More:

- From Guacamole to Tequila, Trump’s Mexico Tariffs Tax Partygoers

- Trump Just Gave Millennial Brunch Favorite Avocado a Gut Punch

- Trump Steps Into a Mexican Labyrinth: Trivedi and Fickling

- Weaponized Trump Tariffs to Hit More Than Mexico: Tom Orlik

--With assistance from Zoe Schneeweiss.

To contact the reporter on this story: Brendan Murray in Washington at brmurray@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Simon Kennedy at skennedy4@bloomberg.net, Paul Sillitoe

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.