Two Ex-Gazprom Executives Help Venezuela Keep Oil Flowing

Two Ex-Gazprom Executives Help Venezuela Keep Its Oil Flowing

(Bloomberg) -- In sanctioned and crisis-torn Venezuela, a little-known company led by former executives at Moscow-based Gazprom PJSC is taking an outsized role for embattled leader Nicolas Maduro as many of his main foreign partners in the oilfields scale back or leave.

GPB Global Resources BV is based in the Netherlands, but it’s run by Boris Ivanov and Sergey Tagashov, both of whom also worked for the Russian government in the past. In the last year, GPB steadily pumped about 10% of Venezuela’s oil in a joint venture with Petroleos de Venezuela S.A, the state-run company known as PDVSA. The operation, named Petrozamora SA, is operating with no company-specific sanctions in the Maracaibo region that helped establish Venezuela as an oil power in the 20th century.

Now, with other projects slowed by an oil rout, a killer virus and concerns over the U.S.’s increasingly aggressive sanctions, Petrozamora’s ability to steer through the most oversupplied oil market in a century will determine just how much revenue is left for the Maduro regime as other countries cut their output in a historic deal aimed at driving up crude prices. Oil fell below $20 a barrel in New York on Wednesday, the lowest in 18 years, amid a record collapse in U.S. fuel demand.

“Petrozamora is now the most productive oil joint-venture in the country,” said Cesar Parra, the head of the oil chamber for Zulia state, home to the Lake Maracaibo region.

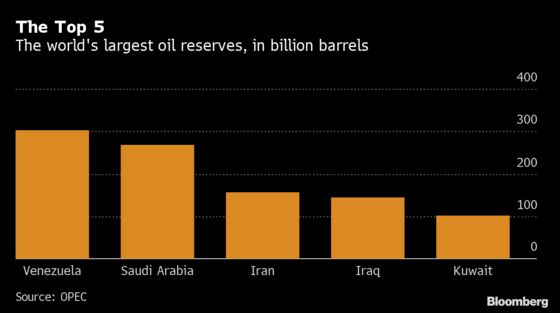

Under coronavirus quarantine like most of the world, Venezuelans are used to shortages after seven years of economic meltdown. But in the past few weeks, as U.S. sanctions tightened with a vise-like grip, something extraordinary has been occurring: the country with the world’s largest oil reserves and one of South America’s biggest refining facilities is nearly out of gasoline. This comes as about 95% of Venezuela’s legal revenue comes from oil exports, according to energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie.

That follows U.S. sanctions put in place over the past two months on two affiliates of Moscow-based Rosneft PJSC for their support of Maduro’s regime. Those sanctions led Rosneft to sell the rest of its Venezuela businesses to the Russian government, which hasn’t disclosed the name of the new company that will manage production.

At the same time, Chevron Corp. is cutting back its Venezuela operations as it awaits a decision, due April 22, on whether its U.S. waiver to work there will be extended. The California-based based company, meanwhile, has told local firms in Venezuela to halt current work on projects including electricity upgrades at oil fields, field maintenance and equipment installation.

Production at Chevron and PDVSA’s Petropiar joint venture was down 58% in mid-March to 50,000 barrels a day, from 120,000 in January. Rosneft’s main venture, Petromonagas, dropped to just 20,000 barrels a day, a quarter of its January production. Meanwhile, Petrozamora’s decline was much less acute: Down just 13% to 68,700 barrels a day from 79,000. Before the March dropoff, the joint operation’s output had been steadily rising, jumping as high as 110,800 barrels a day last year from a high of 95,000 in 2018.

Resilient, Well Positioned

“Oil companies like GPB Global Resources are resilient and well positioned to withstand this challenging environment and weather market volatility,” it said April 7 in a statement on its website. Telephone messages left at GPB’s Moscow offices weren’t returned, while calls to GPB’s Netherlands and Maracaibo offices went unanswered. Additionally, multiple emails sent to each of those offices, as well as through the company’s website, didn’t spur a response.

On paper, PDVSA has full control of operations at legal joint ventures like Petrozamora. Other producers are merely financial partners. In practice, though, these minority partners have assumed more and more operational control as a brain drain, the sanctions, a financial crisis and widespread corruption have left PDVSA crippled.

GPB was founded in 2011, the year before Petrozamora was created. Control of GPB sits with Ivanov and Tagashov, who serve as two of the company’s three managing directors, along with Vladimir Shvarts, whose focus is on Africa and the Middle East.

Ivanov worked on arms control issues for the Russian government in Moscow and Washington before moving into banking, according to the GPB website. He then took a position with the Russian oil and natural gas giant Gazprom, Russia’s biggest company by market capitalization. Tagashov worked at the ministry of foreign affairs at the Russian embassy in Washington before joining Gazprom in Moscow and, eventually, ending up at GPB.

Venezuelan entrepreneurs, often referred to as bolichicos, have also been involved with the company. Francisco Convit, who helped set up Barbados-based Derwick Associates Corp. to sell power plants to the government during a 2009 electricity crisis, was an outside director at Petrozamora from 2015 to 2016, according to Venezuela’s Official Gazette. He has been replaced in that role at GPB by Orlando Alvarado, who previously served as Derwick’s chief financial officer.

Petrozamora’s operations are located smack in the middle of the Bolivar Complex, a group of interconnected fields in the Lake Maracaibo region. It was first discovered in the 1920s, and helped propel Venezuela to become one the world’s biggest exporters by the end of that decade.

Project’s Importance

“Petrozamora’s output is important for PDVSA for several reasons,” said Antero Alvarado, a partner at Caracas-based consultancy Gas Energy Latin America. “It produces all kinds of crude grades, light, medium and heavy. It supplies diluent for the Orinoco Belt heavy crude operations. Until recently it exported Bachaquero crude to the Nynas Swedish refinery, and now it exports crude to Malaysia and Singapore.”

Meanwhile, he said, the company is known as “a client that pays on time to its local oil service suppliers,” no small factor in Venezuela’s struggling economy.

This year, though, is developing a new set of challenges.

U.S. President Donald Trump has tightened oil sanctions and is even sending the military to patrol the Caribbean, ostensibly to combat the drug trade, but also clearly to put additional pressure on Maduro, who was indicted by the U.S. last month, along with associates, for drug trafficking. The U.S. has offered a $15 million reward for information leading to his arrest.

Meanwhile, the global crude glut has producers slashing outlays and scrambling for storage space throughout the industry.“You’ve got the worst of all worlds crashing down right now on Venezuela,” said Schreiner Parker, the vice president for Latin America at Rystad Energy, a consultancy. “At current price levels you have to question the economics of any of these joint ventures.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.