Turkey Isn’t Leaving NATO, But It May Be Breaking With the West

Turkey Isn’t Leaving NATO, But It May Be Breaking With the West

(Bloomberg) -- Just weeks after a NATO summit brushed internal disputes under the carpet, renewed sparring between the U.S. and Turkey points to longer term risks to the alliance.

U.S. Defense Secretary Mark Esper said this week that the North Atlantic Treaty Organization would have to discuss what to do about Turkey’s lack of commitment should Ankara carry through with a threat to block American access to military bases.

Officials at NATO’s headquarters in Brussels say that nobody is yet talking about the base closure threat, let alone Turkey’s potential expulsion from the alliance. Even so, Esper’s exchange with President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has reignited fears that the Western alliance could be on track for a showdown with Turkey - further down the line.

All sides recognize that “keeping Turkey in NATO is in everybody’s interest,” former NATO Deputy Secretary General Alexander Vershbow said in a phone interview. That’s despite real frustrations in Ankara over NATO’s perceived failures to take Turkish security concerns seriously, and within the alliance over Erdogan’s provocative purchase of a Russian S-400 air-defense system.

There is no mechanism in NATO’s founding treaty to allow the expulsion of a member against its will in any case, according to Vershbow, now a distinguished fellow at the Atlantic Council, a Washington think tank.

All of which helps explain why the 29-nation alliance smoothed over equally sharp differences between Turkey and France at the NATO leaders’ meeting in London on Dec. 3-4.

That doesn’t mean those tensions have disappeared: European Union leaders discussed the prickly state of relations with Turkey last week. But the options look limited.

“Nobody’s talking about arms exports sanctions anymore,” Bulgaria’s Prime Minister Boyko Borissov said at the summit, referring to sanctions the EU imposed on Turkey in October after Erdogan sent troops into Syria. Borissov cited the need to keep alive a deal under which Erdogan has stemmed the flow of refugees from Syria and elsewhere to the EU.

On Monday, Erdogan threatened to close two bases if the U.S. Congress adopts into law a sanctions bill penalizing Turkish leaders, energy companies and banks involved in supporting his Syria operation.

The threat does not appear to indicate any willingness on Erdogan’s part to break with NATO, but rather to use the alliance as leverage in a bilateral dispute with Washington.

Neither of the facilities in southeastern Turkey that Erdogan named -- Incirlik air field and the radar installation at Kurecik -- are NATO bases. He did not threaten to close the alliance’s Land Command Headquarters, on Turkey’s Aegean coast.

Incirlik and Kurecik are Turkish-controlled bases that the U.S. has agreement to use, subject to mission-specific permissions from the Turkish parliament. Approvals to use Incirlik for bombing campaigns in Iraq and Syria have been denied often enough that many U.S. combat aircraft have already been transferred to Jordan and the Gulf.

Turkish Control

Though important in the past, Incirlik now acts as a “glorified storage depot” for U.S. tactical nuclear weapons and transfer hub for deployments to Afghanistan, according to Aaron Stein, director of the Middle East program at the Foreign Policy Research Institute, in Washington. Both functions could be moved elsewhere.

Blocking U.S. personnel from Kurecik would have more practical implications for the alliance, because it hosts a U.S.-operated but NATO-critical radar installation that’s positioned to detect any potential ballistic missile launch from Iran. No other NATO member can offer as effective a location.

More important than either base, however, is what Erdogan’s willingness to play chicken shows, according to Stein: a hardening assessment that while Turkey’s military ties to the U.S. and NATO are desirable, they are no longer essential.

Ultimately, Erdogan may be forced to choose whether to back down or carry through his threat to close bases, setting off a new round of retaliations.

Turkey, which has NATO’s second-biggest army after the U.S., has said it will turn on its S-400 system in April. It’s also pushing territorial claims in the Mediterranean to thwart a U.S.-backed natural-gas pipeline from off-shore Israeli and Cypriot fields to Europe, via Greece. Further escalation on either of these issues could raise pressure on Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell to bring the sanctions bill to the Senate floor for a vote, despite his current reluctance.

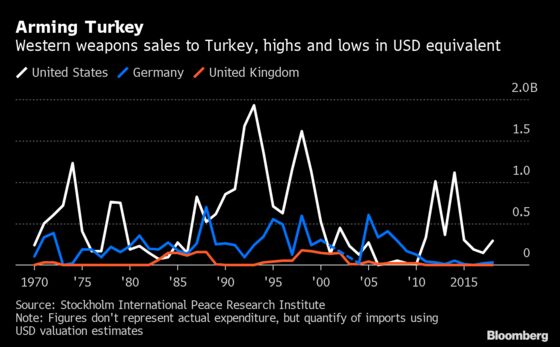

Turkey has clashed with the U.S. and Europe over issues at least as serious as these before, including its 1974 invasion of northern Cyprus. But the Turkey of 2019 is no longer as dependent on Western financial aid or arms imports, and is carving out a more autonomous role often in conflict with U.S. and European policies.

“For five years now, people in Washington have made the same argument that the Turks won’t really buy the S-400s, or that they won’t really invade Syria -- but then they do,” said Stein. “We may well get through this and there may be bluster, but there is a trend and I see no evidence that Erdogan wants to reverse that trend.”

--With assistance from Richard Bravo and Selcan Hacaoglu.

To contact the reporters on this story: Marc Champion in London at mchampion7@bloomberg.net;Jonathan Stearns in Brussels at jstearns2@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Flavia Krause-Jackson at fjackson@bloomberg.net, Alan Crawford, Mark Williams

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.