Why Trump Should Sell Grain to Iran

Why Trump Should Sell Grain to Iran

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- For ordinary Iranians, a sudden shortage of tomato paste, is an omen that U.S. sanctions, combined with their government’s mismanagement of the economy, could make basic foods more expensive, and harder to find. Tomato paste is a crucial ingredient in many Iranian dishes, and inevitably, panic-buying has set in.

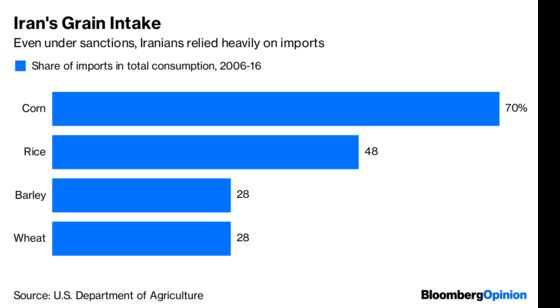

The fears are not misplaced: the sanctions reinstated by the Trump administration will make it harder for Iran to reliably and cheaply import agricultural commodities. And imports are crucial to Iran’s ability to feed its people.

The Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that Iran will need to import 12.4 million tonnes of these critical foodstuffs next year.

One obvious source for these commodities is the very country whose government is making it hard for Iran to get them. Over the past two decades, Iran has intermittently purchased cereals and other agricultural foodstuffs from the U.S. In 2012, at the height of tensions around its nuclear program, Iran purchased 120,000 tonnes of wheat from American suppliers in order to replenish stockpiles after successive poor harvests. Just this past August, as the Trump administration was finalizing the reimposition of sanctions, Iran was the number one destination for American soybeans, buying 414,000 tonnes.

Such exports appear inconsistent with the “maximum pressure” policy being pursued by the Trump administration, which is opposed to any commercial ties with the regime in Tehran. Indeed, the U.S. has so far rejected European requests for sanctions waivers that would help facilitate expanded humanitarian trade. President Trump recently declared that, while he stands “with the people of Iran,” economic havoc is conducive to bringing their government back to the negotiating table:

They have rampant inflation. Their money is worthless. Everything is going wrong. They have riots in the street. You can’t buy bread, you can’t do anything. It is a disaster. At some point I think they’re going to want to come back and they’re going to say, hey, can we do something, and, very simple, I just don’t want them to have nuclear weapons, that’s all. Is that too much to ask?

Trump’s comments echo the vision for the economic destabilization of the Soviet Union that once fixated the American policy establishment. Ronald Reagan, who worked as a political commentator between his time as governor of California and his election to the White House, once railed against U.S. grain sales to the USSR on his syndicated radio show:

If we believe the Soviet Union is hostile to the free world—and we must, or we wouldn’t be maintaining a nuclear defense and continuing in NATO—then are we not adding to our own danger by helping the troubled Soviet economy?... Are we not helping a godless tyranny maintain its hold on millions of helpless people? Wouldn’t those helpless victims have a better chance of becoming free if their slave masters’ regime collapsed economically? One thing is certain, the thread of hunger to the Russian people is due to the Soviet obsession with military power.

By some accounts the Trump administration’s Iran policy is inspired by the Reagan playbook. But despite his deep hatred of the Soviet Union, Reagan actually changed his mind on humanitarian trade with America’s great adversary. In 1981, shortly after becoming president, he lifted the grain embargo put in place by the Carter administration in response the the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Reagan did so against the advice of numerous figures in his administration, who “had the intention of waging all-out cold economic warfare, with the objective of causing the collapse of, or regime change in the Soviet Union.”

There were three compelling reasons to change course. First, the international community did not support the embargo, and countries such as Argentina and Canada compensated for the loss in U.S. exports. Second, the embargo was hurting American farmers already reeling from the fall in grain prices due to the weak economy of the Carter years. Finally, Reagan was eager to show his abilities as a dealmaker. After lifting the embargo, he boasted of renewed trade with a “country our critics say won’t deal with us.”

Today, the same compelling reasons exist for Trump to directly encourage American agricultural trade with Iran. First, international cooperation with his sanctions on Iran is faltering. European governments are seeking to develop new payment mechanisms to sustain trade with Iran, and China, India, and Russia have said that they will maintain their economic ties. The International Court of Justice has recently ruled that the U.S. must remove restrictions on humanitarian trade, including food and agricultural commodities, to avoid violating international law. (The U.S. has rejected the ruling, declaring the court “politicized and ineffective.”)

Second, the Trump administration has been forced to provide American farmers with $12 billion in aid to compensate for the impact on exports and prices of its trade war with China. The collapse of soybean exports to China—down 95 percent—was the primary reason sellers sought to increase exports to Iran in August.

Finally, Trump sees himself as a dealmaker, saying: “Iran is going to come back to me and they’re going to make a good deal.” At the moment he has little-to-no leverage on Iran, and his strategy is looking increasingly wayward.

Trump administration officials are adamant that American “sanctions and economic pressure are directed at the regime and its malign proxies, not at the Iranian people.” If this is really the case, the Trump administration should make humanitarian trade a cornerstone of its Iran policy. To this end, National Security Decision Directive 75, the document which established the Reagan strategy to confront the USSR, offers a model. NSDD 75 included a specific provision for “mutually beneficial trade—without Western subsidization or creation of Western dependence—in non-strategic areas, such as grains.”

The Trump administration will continue to see Iran as an adversary, and the government in Tehran will remain hostile to the U.S. But both governments have an interest in mitigating the direct harm to the Iranian people, and in leaving the door open for improved relations in the future. An expanded trade in agricultural commodities would achieve just that.

One final point worth noting: The U.S. is a significant exporter of tomato paste.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Bobby Ghosh at aghosh73@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Esfandyar Batmanghelidj is the founder of Bourse & Bazaar, a media company that supports business diplomacy between Europe and Iran through publishing, events and research.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.