In a Global Chocolate War, It’s Hershey Against West Africa

In the sweet world of chocolate, it’s seen as a club wielded by the OPEC of confections.

(Bloomberg) -- Some in the world’s chocolate markets see a hefty premium charged by the largest cocoa producers as a blunt instrument wielded by the OPEC of confections -- a tool of a faraway cartel that artificially inflates the price of a precious ingredient.

To the leaders of Ivory Coast and Ghana, where most of the world’s cocoa is actually produced, the argument is something else entirely: a lifeline for farmers and entire economies that would otherwise be held hostage to the vagaries of global commodities markets.

Now those competing viewpoints -- globalization reduced to a chocolate bar -- have collided in spectacular fashion, thrusting the normally secretive machinations of some of the world’s biggest chocolate companies, cocoa traders and processors into rare public view.

The governments of Ivory Coast and Ghana accused Hershey Co., maker of Kisses, Reese’s and other chocolate treats, of trying to skirt around the $400-a-ton premium they’ve slapped on cocoa, aimed at boosting incomes for hard-pressed cocoa farmers. They also said Mars Inc. changed its buying patterns to avoid paying the charge.

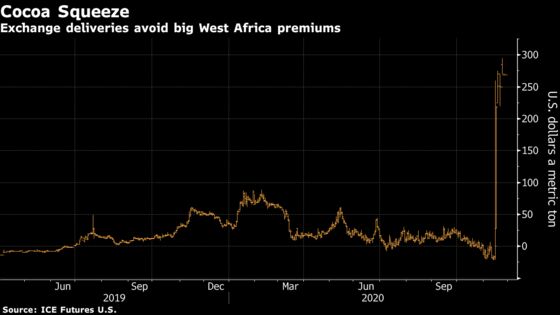

Hershey upended markets in November when it unexpectedly bought large amounts of cocoa through the futures market, squeezing the New York contract.

“Some chocolatiers and trade houses have adopted covert strategies to circumvent the farmer income improvement mechanism with the aim of collapsing it,” Yves Kone, managing director of Le Conseil du Cafe-Cacao, and Joseph Boahen Aidoo, chief executive of the Ghana Cocoa Board, said in a Nov. 30 statement seen by Bloomberg, adding they will do “whatever is within our power to protect the over three million farmers from impoverishment.”

In retaliation, Ivory Coast and Ghana suspended all of the Pennsylvania-based company’s sustainability programs, a move that could hurt sales to ethically minded consumers.

“It is unfortunate that Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana have elected to distribute a misleading statement this morning and jeopardize such critical programs that directly benefit cocoa farmer,” Hershey said in a statement to Bloomberg Monday, adding that it was paying the premium, known as the Living Income Differential or LID, for cocoa purchases from the 2020-21 season. “We buy a substantial supply sourced from West Africa.”

Many cocoa growers in West Africa live below the poverty line, growing beans on only one or two hectares. Chocolate makers and cocoa processors agreed to pay the West African nations the LID and other charges on top of futures prices, but after the pandemic slashed demand, companies needed to cut costs to weather a second wave of lockdowns from Paris to Los Angeles.

Since then, some exporters in Ivory Coast stopped buying cocoa, asking to pay a smaller quality premium known as the country differential, making it harder for the nation to sell about 250,000 tons of cocoa still left on the books. There has also been reluctance to pay the charge in Ghana.

“Ivory Coast and Ghana might be sending a stern warning to the trade, but they also need to be able to sell their cocoa of which they have plenty of,” said Judy Ganes, president of J. Ganes Consulting, who has followed markets for more than 30 years and previously worked for Merrill Lynch. “This is a stare down for sure with gloves off and will be interesting to see who blinks first.”

Hershey’s unexpected move to source cocoa through the exchange sent December contracts on ICE Futures U.S. to a record premium over March. The company highlighted at the time that it was buying cocoa with the LID, but that there were still beans in the market that were sold prior to the implementation of the premium. Hershey also said it needed cocoa from other origins to keep the consistency and taste its customers expect.

“The conspiracy and machinations by your company to evade the payment of the LID demonstrates your passive commitment to improve the incomes of three million West African cocoa farmers,” Kone and Aidoo said in a Nov. 30 letter to Hershey, adding that failure to comply with the orders would mean companies could lose their licenses to operate in the countries.

The regulators also took aim at Mars, saying the maker of Twix migrated the bulk of its cocoa butter purchases from its traditional processors, buying from Asian grinders JB Cocoa and Guan Chong Berhad instead just to avoid paying the premium. Mars said it “categorically disagrees” with the allegations and highlighted that it was the first major manufacturer to support the LID.

The accusations are a further hit to the reputations of chocolate makers, which have come increasingly under pressure for their role in deforestation, child labor and poverty. Earlier this year, a report sponsored by the U.S. government showed that child labor worsened a decade after the $100-billion chocolate industry pledged to reduce it. Hershey is an especially big name, as an American icon whose bars helped power U.S. soldiers across Europe during World War II.

Companies running sustainability programs on behalf of Hershey will also be barred from operating them, the countries said. The move could have “significant implications for cocoa farmers and local communities,” said Antonie Fountain, managing director at the Voice Network, which has called for more industry regulation. The group argued in its 2020 Cocoa Barometer that farmers need to receive about $3,100 a ton, up from $1,800 a ton now.

“Whatever happened in the futures market in the past two weeks has been entirely legal, the question is whether these things should be legal or whether you should be able to force all companies to pay a fair price to farmers,” he said. “Shutting down the sustainability programs is exactly the wrong thing to do because it hurts the farmer.”

Ivory Coast and Ghana also accused Chicago-based cocoa processor Blommer Chocolate Co., which usually processes large amounts of beans for Hershey, of collaborating, according to a separate Nov. 30 letter sent to the Cocoa Merchants’ Association of America in which the countries withdrew their membership from the group.

“We regret that there has been an expression of doubt about the industry’s support of cocoa farmer income levels and, more specifically, the Living Income Differential,” Blommer said in a statement Tuesday. “Despite the impact of Covid-19 on chocolate demand, Blommer expects to purchase its average annual tonnage of cocoa from Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana with full LID pricing for delivery in calendar 2021, with a majority having already been purchased to date.”

The nations also said Olam International Inc., the third-largest cocoa processor, pursued a strategy of reducing the amount of Ghana and Ivory Coast beans from its recipes. The Singapore-based trader reiterated its “strong support” for farmers and boosting their incomes, in line with the objectives of the LID.

“As one of the largest buyers of cocoa from Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana, our commitment is unwavering and we continue to support and purchase cocoa from both countries,’ said Gerry Manley, head of cocoa at Olam.

Ivory Coast’s regulator confirmed the letters and the statement. Fiifi Boafo, a spokesman for the Ghana Cocoa Board, could not comment when reached by phone Monday.

The cocoa squeeze in New York may not be as bad for Ghana and Ivory Coast as the countries have argued so far. That’s because Hershey’s purchase, while big for an exchange delivery, is only a fraction of the countries’ total production. With New York prices much higher than London futures, which form the basis to which the LID premium is added, there’s now a bigger incentive for other chocolate makers to buy again in the physical market, brokers and traders argue.

Ivory Coast and Ghana have in the past threatened to suspend chocolate-makers’ sustainability programs to get companies to buy cocoa with the LID, a tactic that has previously worked. Still, market conditions are “vastly different” now, Ganes said.

While many companies have supported the idea of boosting farmer incomes, many have struggled to manage risk as the Living Income Differential and other surcharges can’t be hedged. That becomes even more accute at times of slowing demand.

The problems Ivory Coast and Ghana “face now are a direct result of trying to impose a poorly thought out premium for all their cocoa no matter how much they produce,” said Derek Chambers, a former head of cocoa at Sucden, who retired in 2018 after 50 years trading. “Both origins will be unable to sell their all their cocoa and will be left at the end of the season with surplus stocks. This is no way at all to help their farmers.”

Ivory Coast and Ghana also said they are reviewing their membership to the Federation of Cocoa Commerce in London and “reconsidering the incentives and the licenses granted to members of the FCC which are directly or subtly rejecting LID.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.