Thank You for Smoking and Saving the Planet

Robert Eccles believes that a good company can be one that does less of something bad, and he uses data to prove it.

(Bloomberg) -- How do you measure a good company? Is it how much money it made in a year? Does it matter if it makes the world a better place? Or if it kills people?

Robert Eccles believes in the possibility that a good company can be one that does less of something bad, and he uses data to prove it. The 69-year-old former Harvard Business School professor has spent four decades accounting for virtue in ways that can’t always be captured in a financial filing. He’s advised Boston Consulting Group and Novartis AG, and he’s the founding chairman of the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), which provides measures for all sorts of factors that can affect a company’s performance but aren’t found in traditional accounting statements. He’s been on a mission to get every business to identify its meaning in the world—he wants them all to write a board-approved statement of purpose by 2025.

Along the way he’s become an elder statesman of ESG. To modern investors these three letters encompass an approach that evaluates companies for their achievements on a variety of environmental, social, and corporate governance factors. The idea, in the most simplistic terms, is to reward the good with more capital while keeping money away from those doing harm.

So it came as something of a surprise to many of Eccles’s colleagues and followers when in his June 2019 monthly newsletter he announced a new client: Philip Morris International Inc. That’s the company that makes Marlboros, Virginia Slims, and Parliaments. He was signing on as an adviser on sustainability, social impact, and investor engagement, and his ultimate goal was to get ESG investors to support its stock.

Eccles wasn’t thinking simplistically. He knew Philip Morris had a lot to crow about on the sustainability front—and that climate-oriented measurements of a company are valuable components of an ESG score. Philip Morris has embraced water initiatives, published a zero-deforestation manifesto, and for six years in a row been put on the “A List” of the CDP, formerly the Carbon Disclosure Project, an influential nonprofit that measures companies’ climate impact.

He also knew that wasn’t nearly enough. Philip Morris’s primary product is addictive and causes cancer and death. Announcing you’ve become an advocate for an international purveyor of tobacco products to the sustainable investment community is roughly equivalent to walking into the rebel base in Star Wars to suggest an alliance with Darth Vader.

“At some point you have to step back from your hatred,” Eccles says, “and ask: ‘What are we trying to accomplish here?’ ”

The fallout came fast. At a conference he attended right after his announcement, a co-panelist refused to appear on the same stage. His friends warned he was tarnishing his reputation. Behind his back there were whispers that he’d lost his way. People clicked Unsubscribe. “A lot of people don’t get his newsletter anymore, they were so appalled,” says Chris Pinney, founding president of High Meadows Institute, a Boston-based policy institute for business leaders interested in sustainability and corporate responsibility.

Some critics are more blunt. “It is extremely disappointing to see a man of his stature working for a company that makes products that kill approximately 1 million people a year,” says Bronwyn King, an Australian radiation oncologist who founded Tobacco Free Portfolios, a nonprofit that crusades for total divestment.

Eccles anticipated the outrage and, truth be told, seems like he would have been pleased had there been a little more. He says activists who’ve pressed investors to divest from tobacco—a practice known as exclusion—have accomplished nothing. Roughly 1 billion people still smoke. Aggressive antismoking campaigns have reduced the percentages, but the total number has remained roughly steady as world population grows and new smokers are added.

In 2016, Philip Morris pledged to begin transitioning its customers away from tobacco to smoke-free products, such as its IQOS heated tobacco stick. And by 2019 the company reported it was spending 98% of its research and development budget to back up this goal.

Antismoking advocates reacted with derision. They pointed out that the cigarette maker didn’t offer a concrete time frame for the full transition and that while “heated tobacco” products might be less deadly than regular cigarettes, this product is hardly good for human health.

But Eccles believes the company is on to something, and he wants to convince investors. “Look, if you don’t want to invest in a tobacco company, or nuclear weapons company, or adult entertainment, or gambling, or food and beverage because it creates obesity, it’s completely fine. But don’t confuse that with creating system-level change,” he says. “Nobody’s given me an argument of how excluding tobacco is going to solve the problem of a billion people smoking cigarettes.”

Eccles is speaking at bullet-train speed now, his impatience with those who might not be keeping up evident. People still treat this like philanthropy, he says of ESG investors, “but we’ve crossed the Rubicon on that.”

In his seminal essay in 1970, future Nobel economist Milton Friedman wrote, “The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits.” Period. It would become the mantra of the next generation of corporate leaders.

But a big reason Friedman had to write that sentence in the first place was that a counterphilosophy was being born on college campuses. As the civil unrest of the 1960s raged, student protesters began organizing against recruiters from Dow Chemical Co., which made Agent Orange, the toxic defoliant being used in the jungles of Vietnam that sickened people.

Religious institutions and universities decided they didn’t want to put their endowments behind war and divested from munitions and chemical companies. After Vietnam, other causes such as South Africa’s apartheid and private prisons prompted divestment in companies deemed complicit.

At the same time, the market was evolving to offer choices to individual investors who were similarly prioritizing ethics. In 1971 two United Methodist ministers struggling to invest church money in companies that didn’t violate their religious values founded Pax World, the first publicly traded mutual fund to use social and financial criteria for investing.

Pioneering socially responsible investors basically tried to screen out the bad: weapons, gaming, alcohol and tobacco—so-called sin stocks. In the early 2000s, though, SRIs began to change their mission from morality to performance. In 2004 the United Nations invited 50 chief executive officers to a meeting to discuss how corporations could help drive positive societal outcomes. Many who attended agreed that considering environmental, social, and governance factors not only led to a better world, it also led to better and more financially sustainable companies.

This brought about the rise of ESG managers, who began to argue that they actually had a superior financial strategy, because they considered dangers ignored by such traditional indicators as earnings reports. By looking at exposure to child labor, wasted energy and water, and diversity within management ranks, the argument went, the investors had a clearer sense of a company’s long-term risks.

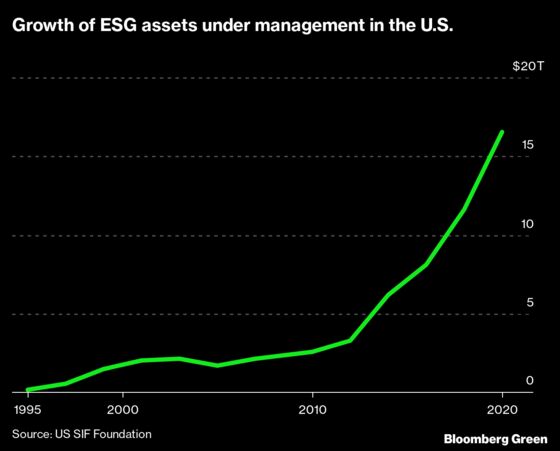

Five decades after Friedman’s declaration, the value of investment funds that apply ESG data to drive investment decisions is ballooning. The research firm Opimas LLC finds that the amount of global assets under management using ESG standards reached $40.5 trillion this year, almost doubling over just the last four years. In mid-November, U.S. SIF: The Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investing released its biennial report and found that assets under money managers saying they incorporated ESG criteria were $16.6 trillion—an increase of 43% from two years earlier.

Along the way, the “E” in ESG became particularly important as the great hope for turning self-interested corporate executives into field commanders in the battle against global warming. The U.S. SIF report, for example, found ESG money managers said they used climate change criteria for at least $4.2 trillion in assets, an increase of almost 40% from two years ago and far more in absolute terms than any other specific ESG issue.

Yet it’s not always clear what change investors are actually buying with their money. Some of the growth in ESG has been almost accidental, because many of the passive ESG funds include high-flying tech giants such as Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, and Netflix.

Meanwhile, some of the most potent activism doesn’t necessarily involve ESG funds at all. Perhaps the highest-profile example is the Climate Action 100+, an investor-led coalition that’s brought together giant institutional investors such as BlackRock Inc. to use their leverage as stockholders to pressure top companies to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions.

Still, most actively managed ESG funds do push to improve corporate behavior for the better, says Tim Smith, director of ESG Shareowner Engagement at Boston Trust Walden Co.

Yet many of the funds, U.S. SIF found, won’t even disclose the criteria they’re using to define ESG. Investors who don’t read the fine print might be surprised to learn that their dollars are going to big oil companies such as Royal Dutch Shell Plc and Total SA.

The two big tools that funds have for pressing companies are exclusion (not buying stock at all) and engagement in some form (buying stock to reward or leverage better behavior). Few funds that use the ESG label and actively manage their portfolio would include tobacco stocks—even to pressure them into better behavior, according to Smith. “It is just not what our investors want,” he says.

Not all experts agree, though, and that gets to the heart of the debate inside the industry. “Definitely there are asset managers and pension funds that would engage around tobacco,” says Kirsten Snow Spalding, the senior program director of the Ceres Investor Network on Climate Risk & Sustainability, one of the groups that helped build the Climate Action 100+.

The context is important, she says, because a company in a suspect sector would have to have a plan for addressing its primary shortcomings. For example, oil giant BP Plc promised this year to reach carbon neutrality by 2050, which will entail slashing fossil fuel production and reinventing itself as a renewable energy company.

Trying to act like a rehabilitated oil company might be a smart move for a tobacco giant. BP, like Philip Morris, spent decades making money from a toxic product and is trying to pivot to an offering that has a future—renewable power—and convince investors it’s sincere. Spalding says a business in a tainted category, though, would have to be way out in front of its competitors if it wants to get an ESG seal of approval. Investors are “looking for the right framework—a commitment that is real,” she says.

The debate has kept the industry growing. “Many investors jumped on the bandwagon without developing their own research or robust strategy,” says George Serafeim, who specializes in social measurement and performance at Harvard Business School and is also a former colleague of Eccles. “The state of play is disagreement and confusion.”

If people are confused by the concept of a virtuous tobacco company, Eccles is happy to educate them. On a recent fall day, after a tour of his capacious backyard garden, complete with chicken coops, in Lexington, Mass., he settles into the parlor to talk more about why Philip Morris deserves to be included in the ESG world.

It’s hard to square this quintessential liberal Northeastern academic, wearing lobster-adorned shorts and sandals, with a guy defending tobacco. The way Eccles puts it, he began to see the potential for his partnership with the company as soon as he met CEO André Calantzopoulos and other company executives. “I was supposed to meet with them for an hour,” he says. “It lasted for five. I said, ‘Here is what you need to do,’ and they said, ‘Yes, yes.’ And they did it.” Calantzopoulos declined to be interviewed for this article.

Disclosure is something of an obsession for Eccles. His early work at Harvard was about the significance of rarely public nonfinancial measures to a company’s success, such things as customer satisfaction ratings and employee turnover. It was his quest to raise the visibility of these factors and create systems to compare them across companies that brought him to the attention of the group trying to start SASB. His original motivation was not morality, but over time disclosure and better behavior have merged in his mind. They form a virtuous circle.

He’s tired of people telling him other companies are more worthy of a vaunted ESG label than Philip Morris. Why have those other corporations been so slow to do basic things, like publish a statement of purpose or be transparent about their business?

Eccles is getting frustrated now, nearly yelling as he talks. “You know what fascinates me about the PMI example? They’re listed on the New York Stock Exchange. They’re subject to U.S. securities laws. So I’m thinking about all this bullshit I’ve been getting for years about fiduciary duty lawsuits. CEOs tell me, ‘We can’t do a statement of purpose. We can’t do it.’ Give me a f---ing break. Nobody’s got a bigger litigation target on their back than a tobacco company. These people aren’t stupid. So you know if a tobacco company can publish a kick-ass integrated report, any U.S. company can.”

He pauses for a break and gulps air. “If you want to entertain yourself over a glass of wine tonight, go look at the Clorox integrated report. It’s like, you know, it’s like a children’s coloring book or something,” he says, noting that the bleach brand’s last sustainability statement was light on details and heavy on pictures.

PMI’s integrated report, by contrast, offers relatively numerous disclosures across four areas the company considers key to its ESG mission. Under “environment,” the report clearly lays out all of its direct emissions as well as emissions from its supply chain and those that come from customers using its products. It also reports how much those have declined by actual tonnage and percentages since 2010. That’s a greater disclosure than one from Dow Inc., the giant chemical company, which put out a climate plan in June, but has received a “B” from nonprofit CDP, or Costco Wholesale Corp., which received a “D.”

Philip Morris also publishes more than a dozen metrics that make tracking its business transformation relatively straightforward, including the total volume of smoke-free units shipped, right above total number of combustible products (i.e., cigarettes), and how both have changed since 2016.

These stats don’t show how good Philip Morris is, per se, but rather how much less bad it says it is than it used to be. In a way, Eccles is helping Big Tobacco—and by extension Big Oil and all other sin stocks—get recognition for doing less harm than before by quantifying the pace of change. Yes, Philip Morris customers are still dying of cancer, but the number has declined and is now lower than those of its competitors.

Certainly, the company argues that it fits squarely into the ESG space of Much Better Than All Those Other Tobacco Companies. It officially spun off from Altria Group Inc. in 2008 and moved its operational headquarters to Switzerland. Under this Continental influence, it began cutting water usage and investing in sustainable agriculture. Carbon emissions declined by more than one-third over the past decade.

The big proclamation came in 2016: Philip Morris would change to a company whose customers use “smoke-free” cigarettes that release tobacco’s nicotine flavor without burning. Nicotine is addictive, but it is the smoke that causes customers to sicken and die, the company argued. Yes, it admitted, these new products are worse than not smoking at all. But the intended users are those who already smoke traditional cigarettes. It pledged to convert 40 million of adult smokers to smoke-free alternatives by 2025.

The company says that it’s already spent more than $7.2 billion developing smoke-free offerings and that 9.7 million smokers switched to PMI’s “heat-not-burn” products by the end of 2019. Perhaps, most significant for investors, in July of this year the U.S. Food and Drug Administration authorized the company to market the new products as more healthful than actual smoking (though some medical experts say it’s not clear that’s the case).

Philip Morris argues that it’s actually providing a virtuous public service. “Why would I engage my company in a multibillion-dollar transformational exercise if I didn’t believe it was the right thing to do?” Calantzopoulos said in a recent interview with the Harvard Business Review. “Even more importantly, how can you refuse people the chance to access a product that is better for their health?”

Sometimes Eccles is cagey about what he’s done for PMI beyond upping its transparency, but sometimes he can’t help but brag. “I get them access to people and places they couldn’t otherwise, because of who I am,” he says. “There wouldn’t have been an interview of André in the Harvard Business Review without me. They wouldn’t have been able to present their long-term plan at the eighth annual CECP CEO Investor Forum without me.”

He pauses to let the significance of those accomplishments sink in. The CECP—Chief Executives for Corporate Purpose—“got a lot of flak” for letting a tobacco company present a transformative vision, he says, “but afterwards people came up to me and said they had been cynical until the presentation.”

Stories like that send shivers through activists like King, of Tobacco Free Portfolios. This is “part of a very long history to improve their social license when, in my opinion, there should be none,” she says.

Big Tobacco’s crimes are, of course, well documented. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says the industry’s products are responsible for roughly 7 million deaths a year worldwide. The industry spent years fighting the scientific consensus on the detrimental effects to health of smoking. Some companies used cartoonlike characters in their advertising, such as Joe Camel, whom critics viewed as making a not-so-subtle appeal to children. (Michael R. Bloomberg, founder and majority owner of Bloomberg News parent Bloomberg LP, has been a longtime champion of tobacco control efforts.) King says they’re still resisting efforts at government regulation in many parts of the world.

Eccles doesn’t blink at the accusations of a dirty history. “It’s horrendous,” he concedes. But, he asks: What does that have to do with the future?

After Eccles’s report and the conferences, it’s not entirely clear what his next steps are for PMI and how he’ll get the company what it wants: more investors.

PMI sent the following statement, which it declined to have attributed to a specific spokesman: “Not all tobacco companies are the same, and PMI is differentiating itself from others within the industry by delivering a smoke-free future. As part of our efforts to deliver on this vision, we established a relationship with Professor Eccles in 2019. As an expert in the field, Prof. Eccles has been providing us with advice and guidance on the areas of Corporate Sustainability as well as ESG and integrated reporting.”

So far, the advice and guidance haven’t made much of a financial impact. The company’s stock, which hit a high in June 2017 of almost $122 a share, has been sinking since. It’s hovered between $60 and $80 for most of this year.

There are a few bright spots. Rupal Bhansali, chief investment officer and portfolio manager of Ariel Investment LLC’s international and global equity strategies, has added PMI to her portfolio explicitly as an ESG play. This may not be so surprising for the author of a book called Non-Consensus Investing. She’s eschewed popular stocks such as Facebook and Apple for low-key but reliable performers like Michelin and GlaxoSmithKline. She declined a request to comment for this article.

Eccles isn’t discouraged by this scant progress; he says he’s in it for the long run. He predicts if Philip Morris does meet its goal of converting 40 million smokers on schedule, there may be a kind of domino effect where countries stop regulating advertising for heated tobacco. Then other companies will get on the bandwagon. He thinks it will be a triumph for the power of integrated reporting. “If PMI can do it, any company can,” he says.

But Pinney of High Meadow, for one, doesn’t buy into Eccles’s theory for change. He says that moving smokers to IQOS instead of getting them to quit altogether is like moving drivers to cars that have better fuel mileage as opposed to electric models. “Is less bad good?” he asks. “Yes, it is good. Is that where real change is going to come from? No.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.