This Man’s About to Get Elected After a $1 Billion Bank Fraud

This Man’s About to Get Elected After a $1 Billion Bank Fraud

(Bloomberg) -- Ilan Shor makes an unlikely champion of the poor, even by the colorful standards of former communist Europe.

Last year, the Israel-born businessman was sentenced to seven years and six months in jail for his alleged part in a $1 billion bank fraud in Moldova that cost its taxpayers the equivalent of 12 percent of the economy. He has a Russian pop-star wife -- her stage name is Jasmin -- and a penchant for high-living in places like the Cote d’Azur.

Still, free on bail while he appeals his conviction, Shor is now a popular city mayor. He denies benefiting from the fraud and has named a political party after himself to run in this weekend’s parliamentary election.

“We’re going to rebuild all of the country’s infrastructure, the way it was in Soviet times!” Shor, 31, told the party faithful this month. His manifesto calls for “the revival of Moldova as a flourishing state in union with Russia.”

Shor’s election campaign and the banking scandal that prompted it go to the heart of a country hollowed out by spectacular levels of corruption. On the fault line between east and west, Moldova was once considered a model reformer by the European Union. It now appears too dysfunctional either to integrate or ignore, a weakly regulated entrepot for potential money laundering, trafficking and Russian meddling on the bloc’s eastern doorstep.

The 2014 scandal Moldovans call “the theft of the century” laid bare the nation’s fragile relationship with democracy, redrew its political map and still shapes attitudes ahead of this weekend’s vote.

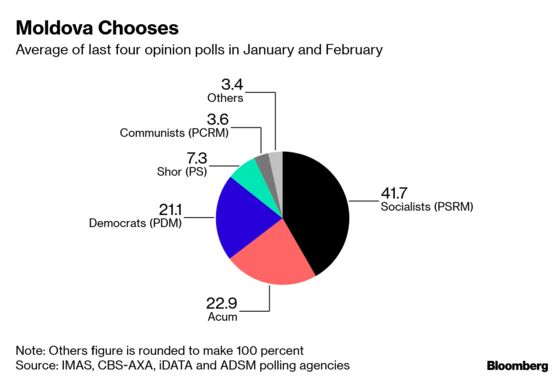

The fraud evaporated support for the main pro-Western party. Its leader, former Prime Minister Vlad Filat, was convicted and jailed, though he maintains his innocence. It also produced a new pro-democracy, anti-establishment bloc called Acum, or Now, and gave a massive boost to the pro-Russia Socialist Party. Its candidate, Igor Dodon, won the presidency in 2016. Opinion polls suggest the Socialists on Sunday will double roughly the 20 percent vote share they won in 2014.

To some, it’s no coincidence that pro-Russians have benefited politically from the fraud. The government accuses its alleged architect, Veaceslav Platon, of being a Russian agent.

Another flamboyant character, Platon is a dual Russian citizen married to a former Miss Ukraine. He was jailed for 18 years in 2017 for his alleged role in the scandal that involved Shor. Platon has also been named in a separate anti-corruption investigation into a $20 billion money laundering scheme known as the Russian Laundromat. He too maintains his innocence.

“The final goal of Platon was to kill Moldova’s economy and to offer the country on a tray to the Russians,” said Mihail Gofman, a former deputy head of Moldova’s National Anti-corruption Center, who investigated the fraud and fled the country in 2016, after somebody cut the brake lines on his wife’s car.

“Do you understand what would have happened to the credibility of the pro-European movement if Russia’s plan had succeeded?” he asked.

Arguably, that credibility was destroyed, with or without a Russian plot.

“We all in Moldova now recognize that we live in a state captured by mafiosi,” Acum’s co-leader, Andrei Nastase, said on a snowy day at his dilapidated party headquarters. He won election as mayor of the capital, Chisinau, last year, only to have the vote overturned by a court. The EU reacted by suspending 100 million euros ($113 million) of aid to Moldova, accusing the government of backsliding on democracy.

The governing Democratic Party of Moldova, or PDM, is led by Moldova’s richest man, Vladimir Plahotniuc. Many people, including Western diplomats interviewed for this article, say he and his allies control the courts, Shor, and, to an extent, the Socialists.

Asked about those allegations, the PDM’s deputy leader said the legal system was being overhauled. He also pointed to difficult reforms implemented on the party’s watch as evidence that Moldova, finally, has started cleaning house.

If, as many expect, Sunday’s vote produces a coalition between the PDM and the Socialists, Moldova is unlikely to make any sudden lurch east.

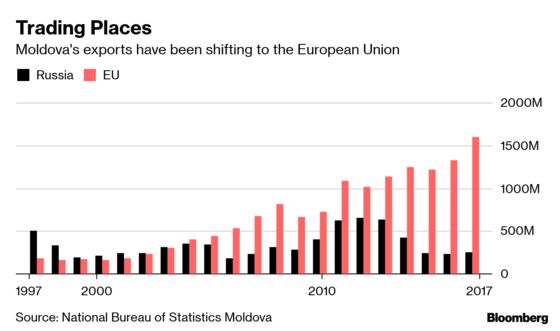

Trade patterns have long since reversed in favor of the EU, which now accounts for 67 percent of Moldova’s exports, compared with 10 percent from Russia. Ruble remittances from migrants working in Russia have more than halved since 2013, while those from the EU more than doubled to overtake them in value, suggesting a shift in migration patterns, too.

The bigger problem may be that the notoriety of the $1 billion bank fraud and the Russian Laundromat affair still dominate views of Moldova among investors abroad. Among other things, that’s made the cleanup harder, because it requires selling troubled banks to foreign investors.

“Four years passed and the banks have completely new boards, but unfortunately compliance officers only read the few articles that get written in the West, and they’re always about the fraud,” says Sergiu Cioclea, who in 2016 was brought in as governor of the central bank to fix the financial industry. He stepped down in December.

There was a lot for Cioclea to do. From the mid-2000s, Moldova’s banks began to be captured by so-called raiders. They used fabricated contracts between fake companies, enforced by corrupt Russian and Moldovan courts, to seize ownership through an array of shell companies.

By 2015, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development was unable to do business with as much as 70 percent of Moldova’s banking industry by assets because it couldn’t identify bank owners, says Francis Malige, who ran the lender’s operations in eastern Europe from 2010 until last year.

The fire hose of suspect Russian money that followed corrupted Moldova’s institutions and deterred foreign investment. The scrubbed proceeds went on to distort real estate, art and other markets in London, New York, Hong Kong and elsewhere.

Put together a judicial system for hire, “the ties to old Soviet Union networks, proximity to Odessa, which is one of the capitals of organized crime in the world, and you had the makings of a perfect location for shady banking,” said Malige, speaking at the EBRD’s London headquarters, where he is now managing director for financial institutions.

Shor used three banks to loan $2.9 billion to his group of 77 companies between 2012 and 2014, according to a December 2017 report by corporate investigators Kroll Inc. commissioned by Moldova’s central bank. The loans were based on fake contracts guaranteed by three Russian lenders with essentially non-existent deposits, the report said.

Money was then laundered through 81 accounts belonging to offshore British, U.S. and other shell companies at two banks in Latvia. There it bounced between the accounts while changing currencies at high speed, using a complex algorithm, according to Kroll. Much of the money went back to the banks in Moldova. $1 billion disappeared.

Shor denies benefiting from the fraud, which he blames on others. In a response to written questions sent over Whatsapp, he cast doubt over the Kroll report’s findings and said he’s willing to help them trace the missing money if they come to see him in Moldova.

“Guys, I am ready to help you, come and I will show you, with documents, bills and bank account numbers, who has the money you couldn’t find and where,” he said.

The three banks Kroll said were used in the theft have been closed. Others were purged of non-transparent shareholders and sold to new investors. The state has begun the process of selling a 64 percent stake in the last big lender, Moldindconbank, which was used for the Russian Laundromat. The potential buyer, awaiting approval by Moldova’s central bank, is a Bulgarian group called Doverie United Holding AD.

“The banking sector has fundamentally changed,” said the central bank’s new governor, Octavian Armasu, ticking off a new legal framework and other repairs made to the financial sector.

The economy has turned a corner, too, with average monthly wages rising to $380 last year, from $270 in 2015. Yet the political damage runs deep and more than two thirds of Moldovans still think the country is headed in the wrong direction, according to a January opinion poll.

Shor, meanwhile, has been able to drum up support on the strength of his time as mayor of Orhei, a neglected town of 20,000 just north of the capital. He’s used some of his fortune to build playgrounds and restore basic services such as trash collection and street lighting. That and the country’s busiest campaign staff should be enough to get him into Moldova’s parliament.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rosalind Mathieson at rmathieson3@bloomberg.net, Rodney Jefferson

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.