Wall Street Is Scrambling For the Exits in Moscow — and Billions Are at Stake

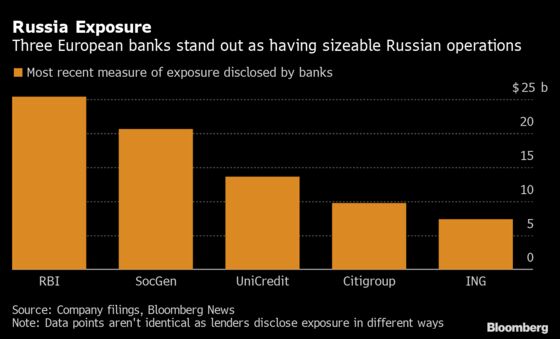

A dozen lenders including Raiffeisen Bank, Societe Generale and Citigroup have about $100 billion of combined exposure to Russia.

(Bloomberg) -- For decades, global finance firms eagerly catered to Russian firms, billionaires and the government. Then tanks started rolling into Ukraine.

Citigroup Inc., which has thousands of staff and billions of dollars of assets in Russia, has said it will cut back much of its business in the country. Goldman Sachs Group Inc., JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Deutsche Bank AG are also heading for the exit, with some financiers relocating to other hubs such as Dubai. They’re being followed by lawyers and other professionals.

It’s perhaps the harshest and fastest exclusion in living memory of a major industrialized economy. The past few weeks have been a frantic dash to understand and implement sanctions that are being continually updated by jurisdictions including the U.S., U.K. and the European Union.

The result is once-bustling desks have ground to a halt, and not just in Moscow. Traders have been left stuck with Russian shares and bonds they can’t shift, while derivatives linked to them have been left in limbo. Private bankers to now-toxic Russian billionaires are drumming their fingers as their clients struggle to pay the cleaners in their London mansions.

For the finance industry, billions of dollars are at stake. A dozen lenders including Raiffeisen Bank International AG, Citigroup and Deutsche Bank have about $100 billion of combined exposure to Russia, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Firms have stressed, though, that their balance sheets can easily absorb any hit to their Russian businesses.

Cutting Communications to Russia

In the hours after Russian troops entered Ukraine, Moscow’s financiers watched the effective collapse of businesses that until last month had looked in rude health. One local investment manager, who asked not to be named, said he was woken by colleagues and raced to the office that morning. His company had been handling $6 billion for pension funds, but now he believes his clients’ assets are likely worth just a fraction of that and perhaps nothing at all.

Another manager in charge of a group of Moscow-based traders, who also spoke on condition of anonymity, said activity levels on his desk had fallen by three-quarters as foreign brokers ceased dealing with his firm. He said he hoped to pick up business others left behind when they quit Russia.

Staff at VTB Bank PJSC, which has been sanctioned by the U.S. and had its British unit frozen, are finding it all but impossible to get many Western firms to return their calls and emails, according to one person with knowledge of the situation. This has left investment bankers struggling to close out trades with counterparties.

Some companies kept in touch with VTB, Russia’s second-biggest bank, and have largely managed to untangle their outstanding trades, the person said, asking not to be identified discussing private matters. Many others severed ties once the sanctions were announced, and may take much longer to unwind business, the person said. VTB declined to comment.

Traders looking to exit equity positions got a glimmer of hope on Wednesday when the Bank of Russia said it was preparing to reopen the stock market for some local shares on March 24, ending the longest closure in the country’s modern history. A ban on short selling will apply, it said.

Leaving Russia for Money and Morals

Bill Browder, once one of Russia’s largest foreign investors and now a prominent critic of President Vladimir Putin, said investment banks had played an integral role in opening up Russia and bringing its money to the rest of the world.

“They made the oligarchs all look legitimate enough for Western investors to throw billions of dollars at these companies and their owners,” said Browder.

One example of the complex web of relationships between Russia and global banks is LetterOne Holdings, the investment firm founded by Russians including sanctioned billionaires Mikhail Fridman and Petr Aven. An HSBC Holdings Plc fund of hedge funds had $547 million of LetterOne money at the end of 2020, and a Blackstone Inc. vehicle had $435 million, Bloomberg has reported. Pamplona Capital Management, which looks after almost $3 billion of LetterOne’s money, has already begun handing back its funds.

And there are corporate clients. JPMorgan has been a big player in the issuance of debt for Russian firms, competing with local giants VTB and Sberbank PJSC as well as the likes of Citigroup, Societe Generale SA, and UBS Group AG.

JPMorgan has said it is “actively unwinding” its Russian business, and it’s chopped Herman Gref, the boss of Sberbank and a former Russian minister, from its star-studded international council.

“Banks should cut business with Russia because it is the right thing to do commercially, but yes, it is a moral point, too,’’ said Natalie Jaresko, who was Ukraine’s finance minister after the annexation of Crimea eight years ago.

Drawing the Line Against Putin's Regime

Former Goldman Sachs banker Georgy Egorov feels queasy about Wall Street’s links with Russia. He called for the bank to withdraw in a LinkedIn post, which was published before the firm said it would quit the country on March 10.

Speaking to Bloomberg after the bank’s announcement, Egorov said Goldman’s exit was difficult, but the right thing to do. “All bulge-bracket investment banks had significant operations in Russia, and to make fees you had to work with a governmental entity, or work for oligarchs,” said Egorov, who was involved in some of the firm’s largest deals in Russia, including the initial public offering of VTB. He moved to the U.K. years ago and now works outside banking.

“For me, personally, it is very difficult because I feel I was complicit. I’m Russian and it is black and white: if you stand for strong corporate governance there is nothing left but just to condemn the war against Ukraine and the Putin regime.”

Why Leaving Russia Is So Tricky For Big Business

Consultants, lawyers and auditors are also splitting from Russia, though it’s a tricky process. The big four accounting firms -- Deloitte, KPMG, PwC and Ernst & Young -- will need to cut ties with their Russian and Belarusian member firms, which are owned by local partners. Those Russian entities can keep working with their clients but no longer have access to the firm's global network.

The detachment process won’t be quick, says Harvard Business School senior lecturer Ashish Nanda, and is likely to get complicated. What if a Russian client, now subject to sanctions, has a subsidiary in Mexico, which is not imposing sanctions? What if the Russian accountants handle work in neighboring Kazakhstan?

Management consultants and law firms can’t so easily jettison their Russian operations. Businesses ranging from McKinsey & Co. and Bain & Co. to Linklaters, Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer and DLA Piper must juggle support for their Russian partners and staff, existing client obligations, and their relationships with the state.

“It’s a distressingly complex calculation,” said Nick Lovegrove, a management professor at Georgetown’s McDonough School of Business who spent 30 years with McKinsey.

In the days following the invasion, McKinsey initially said only work for Russian government entities would cease. Four days later, the firm went further, saying it would “immediately cease existing work with state-owned entities” and not undertake any new client work there, although its Moscow office would remain open. Rivals like Bain and Boston Consulting Group have adopted similar stances.

Professional-services firms that remain in Russia essentially have two choices, according to legal-industry consultant Tony Williams, who once ran the Moscow office of London-based law firm Clifford Chance. “Close the whole thing down or transfer that business to the partners on the ground. I haven’t seen any firms be specific on that,” he said. “You can say you’re temporarily closing, but unless there’s regime change, you’re not coming back.”

As the war heads into its second month, there’s little sign of the situation changing soon. For those who specialize in serving Russian clients, it might be time for a career change.

A broker to some of Russia’s wealthiest businessmen is now looking to become a dealer in classic cars, an executive familiar with the matter said. A British recruiter, who asked not to be named, said he’d had an influx of calls, including one from a Russian private banker whose livelihood disappeared overnight.

He asked the recruiter whether he could transfer over into U.K.-focused wealth. The response: It won’t be easy.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.