(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Successful revolutions must eventually grapple with the question of what to do with that success. The shale revolution is grappling with that right now.

Two veteran shale executives, Tim Dove and Floyd Wilson, have just stepped down from the top jobs at Pioneer Natural Resources Co. and Halcón Resources Corp., respectively. Dove had set a goal of quadrupling Pioneer’s output to 1 million barrels of oil equivalent within a decade, but the spending required has started to grate on investors. Wilson, meanwhile, sold his old company, Petrohawk Energy Corp. to BHP Group Plc (who eventually sold it onto BP Plc after some unhappy times), and then launched Halcón, which lost money, saw its stock collapse, and wound up drawing the attentions of an activist fund.

And that was just overnight. On Friday morning, another activist, Kimmeridge Energy Management Co., announced it had taken a stake in PDC Energy Inc., an exploration and production company with operations in Colorado and Texas. Kimmeridge wants PDC to overhaul its financial priorities, costs, governance and maybe, given the line about “considering all strategic alternatives,” its entire identity.

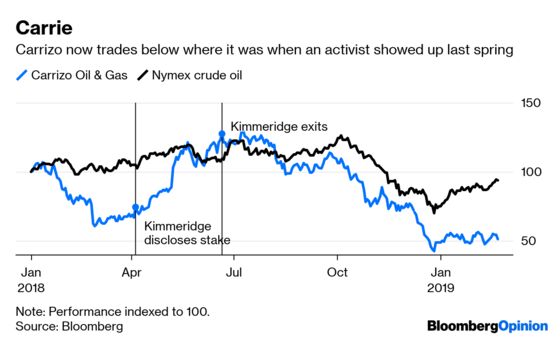

Almost a year ago, Kimmeridge showed up in similar fashion at Carrizo Oil & Gas Inc. Ultimately, nothing came of that; a summer rally in oil prices took the heat off Carrizo’s stock (and offered the fund a graceful exit). It’s worth pointing out, though, that Carrizo now trades below where it was even back then:

I wrote here recently about the mass exodus of generalist investors from the E&P sector. Activists, abhorring a vacuum, have arrived. It all speaks to a fundamental problem: The prevailing financial model for many frackers has hit a wall.

It’s no accident that Kimmeridge kicks off by calling for PDC to raise return on capital employed above 10 percent. PDC’s return averaged less than 1 percent a year in the decade through 2017, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

The sector hasn’t seen an average return on capital above 10 percent in any year since 2006, according to UBS. This is a feature of shale, not a bug. Executives’ compensation packages have typically been skewed toward finding and producing more oil and gas, less so to the profit it generates (see this). Ultra-cheap money helped: The U.S. energy bond market has tripled in size over the past decade. Equity investors, meanwhile, were lured by the promise of growth and the embedded option on oil prices – which, until things went south in late 2014, were assumed to generally keep going up.

The result has been something strangely akin to many a tech unicorn: A breathtaking expansion in market share by shale’s upstarts but little tangible return on the massive investment involved. As for the option value on oil prices, frackers generally reinvested any windfalls (and raised C-suite pay) rather than pay it out. In doing so, they boosted U.S. supply growth just as long-term demand was getting called into question. Little wonder many investors simply gave up waiting around for the payoff.

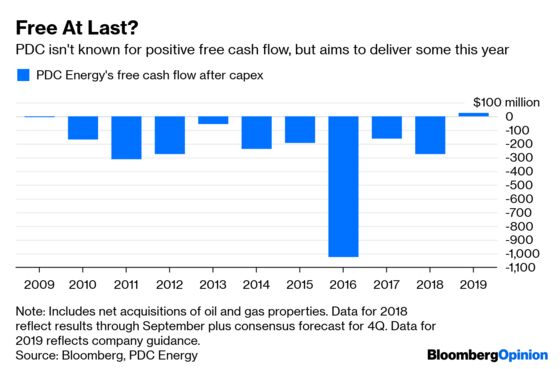

The industry has noticed. Earnings season so far has been less great-quarter-guys and more we-get-it-folks. Capex budgets are being cut, growth plans eased, and talk of free cash flow and dividends abounds. PDC itself announced preliminary guidance earlier this month, including a drop in capex and the prospect of positive free cash flow – which would be quite the novelty:

The stock has rallied 25 percent since then, taking its valuation to the giddy heights of … 3.8 times forward Ebitda (using enterprise value). Clearly, much work remains to be done. And while the new guidance is a good step, that free cash flow figure of $25 million is not only weighted to the back end of 2019, it also adds up to a yield of less than 1 percent. As a means of enticing the generalist back, this barely counts as a window display.

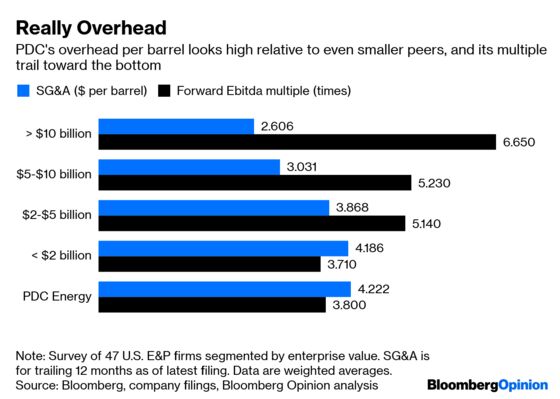

Kimmeridge clearly prioritizes big cuts in PDC’s overhead. The company’s trailing selling, general and administrative, or SG&A, expense in the 12 months ending September equated to $4.22 a barrel. This is high any way you look at it. I took a screen of 47 U.S. E&P companies off the Bloomberg Terminal with a market cap of $500 million or more, segmented them by enterprise value and calculated weighted average SG&A per barrel and Ebitda multiples for each group. PDC’s closest peers would be those with an enterprise value between $2-$5 billion:

PDC targets a 15 percent reduction in its combined lease operating expense and SG&A per barrel. Assuming that was equally applied and the full year figure for 2018 was the same as in the chart above, it would imply holding overall SG&A flat in 2019, based on production growth targets, coming out at about $3.60 per barrel. That would put PDC more in line with its peers – where they were last year, anyway.

Fellow Colorado operator SRC Energy Inc. reported results on Wednesday, with SG&A of just $2.09 per barrel. If PDC could capture just half the gap between that and its own level, the resulting saving of about $50 million would, taxed and paid out, provide a 1.5 percent yield – ahead of many peers and not far off the S&P 500’s 2 percent. Not a bad window display to start with.

The bigger picture here, though, concerns those “strategic alternatives.”

On Thursday, QEP Resources Inc., also targeted by an activist, was telling analysts about its plans to – you guessed it – cut costs and pursue strategic alternatives. As an objective, pushing SG&A below $3 a barrel by 2020 – cutting the absolute dollar figure by $70 million in the process – got a slide all to itself. Still, with Elliot Management Corp. having actually made a buyout offer, and the company saying “a number of companies” have expressed interest, I’m guessing QEP’s road to efficiency ultimately runs through a data room.

The whole reason to own smaller companies is that they tend to grow quickly. But if a decade of growth with not much to show for it has turned off investors, and talk of oil-price leverage prompts eye-rolls, then what do small E&P stocks really have to offer here? Efficiencies and cash yields are usually the preserve of bigger companies (look at ConocoPhillips). Look back at that chart and you can see a clear advantage to scale, with lower unit costs and higher multiples for the bigger companies. As a bonus, consolidation, by slowing U.S. output growth, would also tend to support oil prices, or at least moderate a sustained headwind.

Cutting costs, realigning oil bosses’ pay and pushing more cash out the door rather than down new wells offer the best way of luring investors back. For shale’s smaller players, that is now an imperative – and getting together or selling out may offer the fastest way of getting there.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Mark Gongloff at mgongloff1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.