The Meteoric Rise of Billionaire Len Blavatnik

The Meteoric Rise of Billionaire Len Blavatnik

(Bloomberg) -- There are billionaires, multi-billionaires and then there’s Len Blavatnik—a man whose net worth is so big, his network so broad and business goals so ambitious that, these days, he’s seemingly everywhere.

Scarcely a month goes by without news of a splashy purchase, major donation or black-tie appearance by the 61-year-old, who was born in Odessa, Ukraine.

Three weeks ago, he feted the honorees of the 2019 Blavatnik Awards for Young Scientists in Israel at a lavish ceremony in Jerusalem. In February, donning a purple paisley jacket, he presided over Warner Music’s Pre-Grammy Party, rubbing shoulders with pop stars Rita Ora and Lizzo. In November, he gifted $200 million to Harvard Medical School, and in June he bought London’s historic Theatre Royal Haymarket for a reported $59 million.

Such largesse isn’t unheard of for a billionaire, nor is the frequent hobnobbing. What’s remarkable is the speed at which his wealth has swelled and how quickly he’s expanded his influence across finance, entertainment and society.

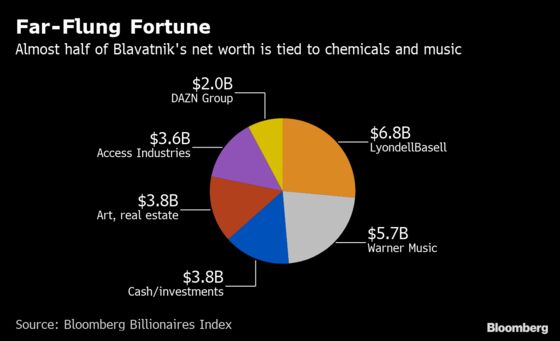

Also striking is how the components of his $25.7 billion fortune contrast with how and where he began to build it. Blavatnik, a citizen of the U.S. and U.K. (he has a knighthood and you can call him “Sir Leonard”), has pumped the billions he earned through privatized factories and oilfields into assets that are worlds removed from his early investments in post-Soviet Russia.

The boldest gambit in Blavatnik’s transformation, Warner Music, has paid off handsomely. The record label he bought in 2011 for $3.3 billion may be worth more than $6 billion today, thanks to a music-industry rebound.

Blavatnik’s purchase, seen as rich at the time, now looks downright canny.

Global recorded music sales were $15 billion when he made the deal, with just a tiny fraction of that coming from streaming. By 2018, total sales had jumped to $19.1 billion, and the share from streaming had soared more than 900 percent. That resurgence is boosting multiples in an industry that not long ago was struggling to convince investors of its viability.

Warner’s “revenue has grown the fastest in percentage terms for three years running,” said Mark Mulligan, managing director of London-based Midia Research. If that trend continues, it “could end up the second-biggest record label.”

Rival Universal, which is being shopped by owner Vivendi SA, has also seen its potential value jump. Universal, which controls 31 percent of the music market to Warner’s 18 percent, could be worth 29 billion euros ($32.3 billion), Deutsche Bank AG said in a January research note.

Blavatnik declined to be interviewed for this story, but he said through a spokeswoman that Warner is worth $3.3 billion. Equity compensation distributed to executives at the end of fiscal 2018 was based on a valuation of $3.2 billion, though it could easily be worth twice that much, said one industry analyst, who asked not to be identified discussing unpublished estimates. The spokeswoman wouldn’t elaborate on their valuation.

Warner’s resurgence is just one reason why Blavatnik’s fortune has soared 56 percent in the past five years, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index, a ranking of the world’s 500 richest people. He’s catapulted to No. 31, from 48, in that span.

Blavatnik’s property holdings, including a mansion on London’s Kensington Palace Gardens, the Grand-Hotel du Cap-Ferrat in the French Riviera and more than $275 million of Manhattan homes, have benefited from a decade-long surge in real estate prices that has only recently cooled. Through a New York-based holding company, he’s invested in designer Tory Burch, Dutch payments processor Adyen NV, Spotify Technology SA, Amazon.com Inc., Facebook Inc. and the Broadway hit “Hamilton”.

Even his wildest bets have turned to gold. Take LyondellBasell Industries NV, a chemical giant Blavatnik engineered when he bought Dutch chemicals maker Basell NV in 2005 and hitched it to Houston-based ethylene producer Lyondell Chemical Co. two years later, with the help of $20 billion of debt. Shortly after he completed the deal in December 2007, a succession of calamities—hurricane-related plant closures, a fatal crane collapse, the financial crisis—almost destroyed the business.

It filed for bankruptcy in 2009, costing Blavatnik at least $1 billion and prompting a lawsuit from creditors that would drag on for almost a decade before he prevailed.

Blavatnik teamed with private equity firm Apollo Global Management LLC to resurrect the company. He bought back the shares he’d lost during bankruptcy, and when the company returned to the market in mid-2010 his stake was about $900 million. Over the next three years, he picked up an additional $1.5 billion of shares. A steep drop in natural gas prices, fueled by the U.S. shale revolution, helped the stock more than quadruple since the company relisted. Blavatnik’s total investment of roughly $3 billion is now worth $6.8 billion. He’s also pocketed $3.8 billion from share sales and dividends.

“Len has a natural gift for zeroing in on complex problems, distilling them down to their essence and hammering out creative solutions,” said Apollo co-founder Josh Harris, who worked closely with Blavatnik through the restructuring. “What emerged was an exceptional investment for our investors, and a much stronger company.”

The brush with bankruptcy hasn’t dimmed Blavatnik’s appetite for big bets. He’s spent hundreds of millions of dollars building video streaming service DAZN into one of the world’s largest sports broadcasters. Last year, he hired former ESPN President John Skipper as chairman, signed a $1 billion, eight-year deal with promoter Matchroom Boxing and awarded Mexican pugilist Canelo Alvarez what was then the richest contract for an athlete in sports history: $365 million for 11 fights.

Shiny media companies are a far cry from where his money was minted.

The foundation of Blavatnik’s fortune was mostly laid in the “aluminum wars” in 1990s Russia. After attending Moscow State University, he emigrated to the U.S. shortly before his professor parents and received a master’s degree in computer science from Columbia University. He worked at Arthur Andersen and General Atlantic Partners and got an MBA from Harvard. But the opportunities for enrichment in post-Soviet Russia soon lured him back.

After setting up a holding company in New York, Access Industries, he partnered with Viktor Vekselberg and began buying newly privatized aluminum plants. Competition was ferocious, with motley investors like Blavatnik and Vekselberg scrapping alongside criminal groups and contending with intimidation and violence. Years later, Roman Abramovich testified in court that he had to be persuaded to invest because “every three days someone was murdered in that business.”

Blavatnik and Vekselberg emerged victorious. Their company, Sual, was later combined to form United Co. Rusal, today the world’s second-largest aluminum producer.

Blavatnik bristles at being called an oligarch, as he often is in news reports. The “highly offensive” term doesn’t apply to him, said his spokeswoman, citing his absence from a list of designated oligarchs published by the U.S. Treasury Department in January 2018. A refusenik, he was stripped of his citizenship after leaving the Soviet Union in 1978, and he’s never been involved in Russian politics, she said.

In 1997, Blavatnik and Vekselberg teamed with Ukraine-born billionaire Mikhail Fridman to buy a 40 percent stake in TNK, a former state-owned oil company with interests in Siberian oilfields. Two years later, on the cheap, TNK acquired a productive subsidiary of a competitor, partly owned by BP Plc, that a local court had declared bankrupt. BP fought to block the purchase, failed and ultimately paid almost $7 billion for 50 percent of TNK, which was renamed TNK-BP. The partnership was contentious, and in 2013 the company was sold to state oil giant Rosneft in a record $55 billion deal heralded by President Vladimir Putin. Blavatnik, Vekselberg, and Fridman and his other partners reaped a total of $27.7 billion.

Flush with cash, Blavatnik turned his focus more fully on his budding media empire. The industry was high-profile and miles removed from post-Soviet industry.

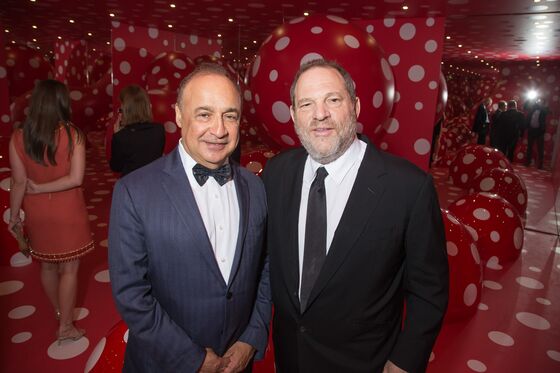

Keenly interested in the movie business, he strengthened his business ties with Harvey Weinstein, lending $45 million to Weinstein Co. in 2016. (Access later sued the company and Weinstein personally for breach of contract after allegations against the co-founder surfaced.) Blavatnik was also behind the taking private of Perform Group, a U.K. sports and entertainment rights company, and led an unsuccessful bid for Time Inc.

In April 2017, he bought a controlling stake in film finance company Ratpac-Dune Entertainment from Australian billionaire James Packer for an undisclosed sum. The deal briefly made Blavatnik a partner of Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin and producer Brett Ratner. Mnuchin divested his interest shortly thereafter to avoid potential conflicts of interest.

Despite their importance in building his fortune, Russian assets make up just a sliver of Blavatnik’s current holdings. The biggest is a $400 million stake in Rusal, which he owns through a joint venture with Vekselberg. The value of the stake has climbed 6 percent since the U.S. lifted sanctions imposed on the company last year in response to Russia’s “malign activities.”

A political donor for years, Blavatnik has given $4.5 million to various U.S. candidates and committees from both parties, including $1 million to President Donald Trump’s inaugural committee, according to Federal Election Commission records dating back to 1996.

Blavatnik’s spokeswoman said his donations have been solely aimed at furthering “a pro-business, pro-Israel agenda.”

Even so, his name has been sucked into the media maelstrom that focused on Russian influence in the Trump campaign, highlighting his connection to Vekselberg, whose cousin Andrew Intrater also donated to the inaugural committee. Vekselberg was personally sanctioned by the U.S. last year and lost $2.2 billion in the wake of the penalty.

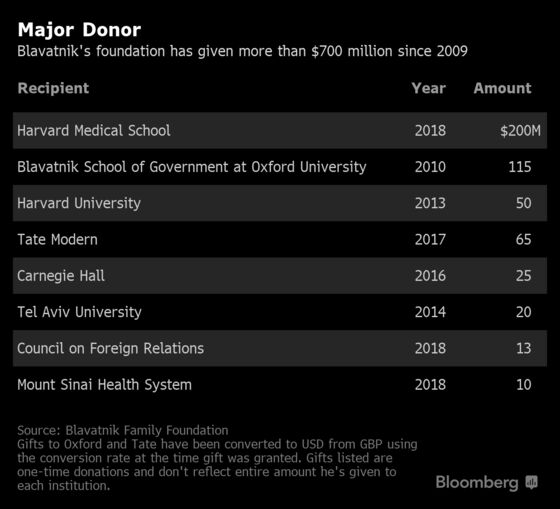

Around the time of his cash-out from TNK-BP, Blavatnik accelerated his philanthropic giving. Since 2009, he has donated more than $700 million through his Blavatnik Family Foundation, mainly to elite institutions supporting medical and scientific research.

Even that has exposed him to criticism. Charles Davidson, the director of the Kleptocracy Initiative at the Hudson Institute, a Washington think tank, resigned in protest late last year after Blavatnik sponsored a table at its annual gala.

“Kleptocracy has entered the donor pool of Hudson Institute,” Davidson told the New York Post.

A spokesman for Blavatnik said the Hudson Institute specifically thanked his foundation for the gift and informed him in writing that Davidson’s departure was "planned and overdue" and that he had used the donation and gala as a "convenient way to create a spectacle." Davidson and the Hudson Institute declined to comment.

Blavatnik’s giving has also caused discomfort in his adoptive Britain. Two years ago, a professor of government and public policy at the University of Oxford’s Blavatnik School of Government, established through a 75 million pound gift ($115 million at the time), quit in protest of the patron’s support for Trump’s inaugural committee.

The controversies have stung Blavatnik and stymied attempts to distance himself from the political entanglements of old colleagues. He was bothered that lawmakers were probing Mnuchin’s decision to lift sanctions against Rusal and his connections to Blavatnik, according to a person who asked not to be identified sharing private information. Mnuchin has stated he didn’t sell his stake to Blavatnik or any of his firms. There’s no indication Blavatnik himself was investigated.

Blavatnik finds the insinuations hurtful and he’s proud of his heritage, the person said. He even named his super-yacht Odessa, after his place of birth.

—With Robert Lafranco, Alex Sazonov, Lucas Shaw, Anders Melin, and Stephanie Baker

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Pierre Paulden at ppaulden@bloomberg.net, Peter Eichenbaum

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.