The Get-Rich-Quick Scheme That Almost Killed a German Soccer Team

An electrician’s odd plot to make $607,933.50.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The bombs were ready to detonate when the black-and-yellow bus pulled into L’Arrivée Hotel & Spa, on the outskirts of Dortmund, Germany, on April 11, 2017. The driver, Christian Schulz, had arrived to take the players of Borussia Dortmund, one of the country’s best soccer teams, to their Champions League tournament quarterfinal in nearby Signal Iduna Park. Dortmund was set to play AS Monaco and hoped to move a step closer to Europe’s most prestigious club trophy.

Shortly before 7 p.m., the players climbed aboard the bus. On schedule, Schulz set off on the 15-minute drive to the stadium near the center of Dortmund, a city of 600,000 that’s considered the faded capital of the German rust belt. Matthias Ginter, a soft-spoken 23-year-old center back, settled into a seat in the rear. Since joining the team in 2014, Ginter’s strong play has helped keep it near the top ranks of European soccer. He’d already lived through one of the most traumatic recent moments in the sport. Two years earlier, Ginter was playing in an exhibition match between the German and French national teams in Paris when three suicide bombers blew themselves up outside the stadium, marking the beginning of a terror attack that killed 130 people across the city. He rationalized it as the kind of thing that happens only once in a person’s life.

The three bombs in Dortmund were filled with metal pins and hidden on the side of the driveway, about midway between the hotel and the street. As the bus approached the road, the bombs exploded, sending a cloud of heat, dirt, and metal shooting through the air. One of the bus’s windows was punctured, and glass splinters flew through the interior. A pin shot into a headrest near center back Marc Bartra, barely missing his head. Schulz stepped on the gas and stopped a few hundred feet away. It seemed like a miracle: Aside from Bartra, who was put into an ambulance with an injured wrist, nobody was hurt. Most of the pins were scattered across the pavement.

No soccer team had ever been assaulted like this. In previous months in Germany, Islamic State terrorists had set off a suicide bomb at a music festival, killed nine people with a truck, and attacked train passengers with an ax. Two years earlier, a match between Germany and the Netherlands was called off after Israeli intelligence suggested an imminent bombing by Islamic extremists. Many in the German media assumed the same groups were behind this attack.

As police arrived, they had no way of knowing the bomber was in L’Arrivée’s restaurant, eating steak and sweet potatoes.

The lead investigator from the State Office of Criminal Investigation got to the scene a few hours later. “There were a lot of places where there might be clues, because everything had been launched far by the explosion,” he said later in courtroom testimony. They found remnants of an antenna and a cellphone. Each of the three bombs had consisted of a self-made explosive, 30 metal pins, and an electronic fuse that could be triggered from a distance—and which could have been assembled by an Islamic terrorist.

The search also uncovered three copies of a letter near the bomb site claiming the attack on behalf of Islamic State. But it perplexed investigators. It didn’t have an Islamic State logo. It was riddled with simple spelling errors yet used an advanced vocabulary, as if a native German speaker might have written it with the intention of sounding foreign.

A passerby came across a charred site in the nearby woods where the attacker had apparently assembled the bombs. The location was burned, seemingly to hide evidence, but the site was also oddly obvious. Another letter appeared on a far-left website claiming the attack had been carried out by “anti-fascist” activists. The Berlin newspaper Der Tagesspiegel got an email stating that the bombing had been a far-right attack on “multicultural” Germany. Police searched the apartment of an Iraqi man suspected of being an Islamic State follower and interrogated a Middle Eastern man with a L’Arrivée umbrella at home, but none of the leads went anywhere.

For Dortmund players, the period after the bombing was a blur of anxiety. Ginter said he considered giving up the sport altogether. “I was worried whether it would be worth going through this risk over and over again,” he said. Management told players that the quarterfinal could be delayed by only a day. “Nobody from the team wanted to play the next day,” Ginter recalled. But, he said, “it was a Champions League quarterfinal.” Dortmund lost 3-2.

The German media debated who would deign to attack such a German institution as soccer. Founded in Dortmund in 1962, the German Bundesliga is among the most popular and profitable leagues in the world. The team, known as BVB in Dortmund, is the city’s most cherished icon and one of its few bright spots. Almost the entire city center was obliterated during World War II. On Westenhellweg, Dortmund’s pedestrian shopping street, it’s impossible to walk more than a few feet without seeing the BVB logo.

The city loves soccer so much that in 2009 it was selected to become the home of the German Football Museum. Its four floors hold hundreds of items and one unlikely clue to what motivated the attack: a display showing BVB’s publicly traded shares, with a green line tied to the team’s wins and losses that zigs up and mostly down from 2000 to 2015.

In 2000, Dortmund became the first and only club in Germany to list itself on the stock exchange, in an effort to compete with top-tier teams in signing expensive players. From 1995 to 2017, average player salaries in the Bundesliga almost tripled. BVB’s chief executive officer, Hans-Joachim Watzke, told Business Insider in 2013 that the team was like a factory that churns out victories and “the players are the equivalent of the machines. The only problem is that other teams are constantly trying to buy away the machinery.” Going public gave Dortmund about €140 million ($152 million) to secure its roster.

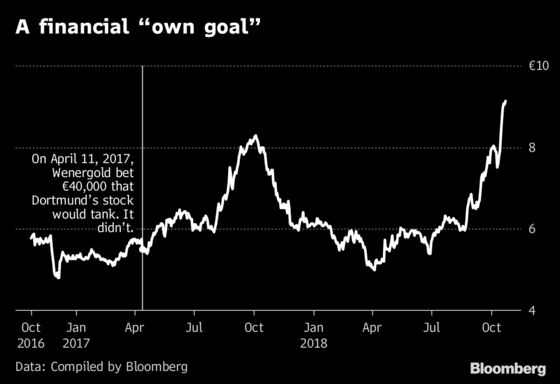

Shortly after the attack, BVB’s lawyer got an email from a man named Rudolf, a Dortmund fan and sports stock trader in the Austrian town of Bad Ischl. “Yesterday, strange ‘certificate option’ purchases took place on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange,” it began. On the day of the attack, he wrote, someone had purchased 60,000 BVB put options—a wager that the shares would fall below a certain price by a certain date. “A purchase like this is only rationally explainable,” he wrote, “if the buyer was expecting the stock value to go down very rapidly.” This kind of drop, he pointed out, wouldn’t happen if Dortmund lost a game. It would require something more serious, like losing players, or the entire team, in a terror attack.

Most short sellers are just looking for shares they expect to fall and trying to profit from the downward spiral. The classic example is Jim Chanos, founder of Kynikos Associates Ltd. (“cynic” is derived from the Greek word kynikos), who shorted Enron Corp. stock before the company collapsed in 2001. But it’s not unheard of for someone to try to create a catalyst to sink stocks. Earlier this year, hedge fund manager Bill Ackman exited a $1 billion bet against Herbalife Nutrition Ltd. after he spent years unsuccessfully trying to convince regulators that it was a pyramid scheme that should be shut down. More recently, Tesla Inc. founder Elon Musk alleged that short sellers had hired people to sabotage robots at the company’s Fremont, Calif., plant, though there’s no proof. There may not be a direct parallel to bombing a soccer team, but in February 2017 a Florida man was charged with attempting to blow up Target stores. He planned to tank the company’s stock by putting explosives disguised as food items on shelves.

Investigators contacted Commerzbank AG, the German bank whose subsidiary, Comdirect, processed the options. Dortmund wasn’t a commonly traded stock, so purchasing €40,000 worth of BVB derivatives was unheard of. Put options are high-risk. They decrease in value as they approach their expiration date, in this case in June, and can depreciate dramatically if the stock price rises. Even more suspicious, one of the purchases had been made online only a few hours before the bombing, using an IP address at L’Arrivée Hotel.

Interviews with employees revealed that a twentysomething man with a Russian accent had checked in two days before the attack and insisted on a room with a view of the entryway. It wasn’t the man’s first visit to the hotel: He’d spent the night at L’Arrivée in early March, more than a month before the attack. Investigators soon identified the man as Sergej Wenergold, a 28-year-old German citizen living in the southern city of Rottenburg am Neckar.

For a week, investigators hid outside Wenergold’s apartment. He worked as an electrician at a biofuel heating plant in the nearby city of Tübingen and didn’t fit the terrorist profile. He had no criminal past and no connection to far-right, far-left, or Islamic extremists. In his free time, he crossbred plants and tinkered with drones. He wasn’t a soccer fan, and he didn’t seem to need money. He had a stable income and no apparent gambling problem or debts. Still, he was the only suspect. On April 21, 10 days after the attack, police surrounded his car as he arrived at work and arrested him.

Wenergold was a Russlanddeutscher, as Russia’s German ethnic minority is called. Before World War I, more than 2 million ethnic Germans lived in the Russian empire, and several hundred thousand remain in its former territory today. Growing up in the Russian city of Chelyabinsk, Wenergold was bullied for his ethnic background, and a teacher taunted him with Nazi jokes. In 2003 the family joined the large number of Russlanddeutsche returning to Germany.

They moved to the southern state of Baden-Württemberg, part of a region known as Swabia, often mocked in Germany as obsessed with order and fiscal stability. His father was a welder, and his mother, who spoke broken German, worked as a hotel cleaner. Despite having been in Germany half of his life, Wenergold had a strong accent that made him self-conscious in groups of Germans.

In interviews, mental health professionals testified, Wenergold was withdrawn. At first he answered questions with only a few words, leading them to question his intellect. But as the conversations continued, they saw that his reticence camouflaged intelligence. He displayed a remarkable level of self-control, too. For the past several months, he had been self-medicating with the opioid Tramadol to control anxiety.

A psychological assessment concluded that he’d struggled with mild depression for much of his adult life. Sometimes he drove recklessly on country roads, as if daring himself to get into an accident. In 2013 he made a halfhearted suicide attempt by crashing his hang glider into some trees.

Initially, Wenergold denied that he carried out the attacks. But as time dragged on, he admitted that he’d built and set off the bombs and purchased the put options. He claimed he hadn’t wanted to kill anybody, but merely to create the illusion of an Islamist terror attack. The idea for the plot, he later testified, came to him while watching coverage of the 2015 Paris spree. After the killings, he looked at the valuations of French companies. “I saw that the share prices had gone down, even though the attack didn’t target anything economic,” he later testified. “I thought if there was an attack that explicitly targets a company or something like that, then its stock value would go down as well.”

If Wenergold shorted Dortmund and simulated an Islamic terror raid against the team, he figured, he could make money. Losing one game might not have a dramatic effect on it, but if “the team lost in the Champions League, and many people thought players were traumatized and couldn’t keep playing so well,” he recalled, “then a negative trend could establish itself.”

For the past several months, Wenergold’s trial has been taking place on the top floor of Dortmund’s 19th century state courthouse. Wenergold is charged with 28 counts of attempted murder, and the proceedings have centered on whether he intended to kill the players or merely scare them. Wenergold’s lawyers have argued the latter. Because jury trials don’t exist in Germany, the case will be decided by a team of five judges. A verdict is expected in the next few months with a maximum sentence of life imprisonment.

Throughout the trial, Wenergold has maintained an eerie composure. Even during emotionally fraught testimony, including tearful descriptions of the attack by Ginter and other players, he has sat silently, staring at his hands, dressed in his collared shirt and dark blue cardigan.

The biggest question looming over the case has been the hardest to answer: Why would Wenergold attempt to pull off such an act? It may have had less to do with proving himself a financial whiz than proving himself to a woman.

On April 18, just more than a year after the bombing, his ex-girlfriend, Rebecca, testified. The 22-year-old spoke with a youthful bubbliness and a heavy Swabian accent. Wenergold had loved her, she said, but the relationship was largely an arrangement of convenience for her.

They started dating in 2014 after meeting at church in the city of Freudenstadt, where Wenergold’s parents lived. Rebecca was struggling at home. Her mother was mentally ill and prone to fits of rage, she testified, and she focused many of her outbursts on Rebecca. “I couldn’t take it anymore,” she said. A few weeks after meeting Wenergold, Rebecca moved in with him and his family.

As time went by, she felt isolated. “He had difficulties with German people. He was afraid people wouldn’t understand him because of his accent or that he wasn’t good enough,” she said. When she considered breaking up with him, she testified, he told her that he might kill himself. On several occasions she got into her car with plans of never coming back, but then she realized that she didn’t want to return to her mother.

Wenergold had looked into buying a house for them and his parents to live in, a chivalrous idea that was also a sound financial investment. In speeches extolling the virtues of austerity policies, German Chancellor Angela Merkel sometimes summoned the image of the “Swabian housewife,” a mythical embodiment of the region’s financially prudent mindset. The money he hoped to make from his plan might have allowed them to start a new life. Wenergold said they had talked about getting married and having children and supposedly set a tentative date for 2019.

But in early 2016, she figured out how to make a clean break: a program starting in January 2017 at a Bible school on Australia’s east coast. “So I wouldn’t hear about it if he did something to himself,” she testified. In the fall of 2016, Wenergold began acting strangely, staying later at work and telling Rebecca that she would “soon be seeing a surprise.”

Rebecca dumped him via text on Feb. 13, 2017, the day before Valentine’s Day, and then blocked him on social media.

It was around this time that Wenergold firmed up his plans. He took out a loan to pay for the options and made two 300-mile trips to Dortmund to determine a location for the bombs and observe the team’s movements. From his online research, he knew the dimensions of the bus, which allowed him to calculate the spacing for the explosives. He also settled on an event—the Champions League quarterfinal—to maximize potential impact on BVB stock and wrote a fake Islamic State letter based on what he found online.

He claimed to have modeled the bombs on a Soviet explosive device with only a few instructions from the internet. He was familiar with the mines, he later said, from his service in the German army. Most of the ingredients were purchased at hardware stores or online and stored in ventilation spaces at work or in a nearby forest. He made his final preparations the night before the attack in the wooded area near the hotel. After setting the site on fire, he affixed the bombs.

The day of the bombing, Wenergold’s determination wavered—he was nervous. He checked on the explosives. He went on walks. He spent part of the afternoon at a local brothel. Before the bus arrived, he bought the options on his laptop, and at 7:16 he set off the remote detonators as the bus drove away. As traumatized players left the bomb site, he made his way to L’Arrivée’s restaurant.

Wenergold drove home, but apparently he continued thinking about his novel strategy for gaming stock prices. “The question,” he testified, “was whether I should try it one more time, bet it all on one card.” When investigators examined his computer, they found searches for “cableway stock” and several Alpine cable-car lines, including one carrying passengers to Hitler’s former mountain retreat southeast of Munich.

According to investigators, Wenergold could have made as much as €570,000 ($607,933.50) in the unlikely event that BVB stock hit zero in the immediate aftermath of the attack. But his scheme didn’t pan out. By the time the German stock exchange opened the next day, April 12, the limited injuries had been widely reported and management had already announced a new date for the quarterfinal. BVB stock briefly dropped 2 percent, then more than recovered by the end of trading, leading Wenergold to sell most of his options the next day at a loss.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Bret Begun at bbegun@bloomberg.net, Jim Aley

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.