The EU’s Carbon Market Is About to Enter Its Turbulent 20s

The EU’s Carbon Market Is About to Enter Its Turbulent 20s

(Bloomberg) --

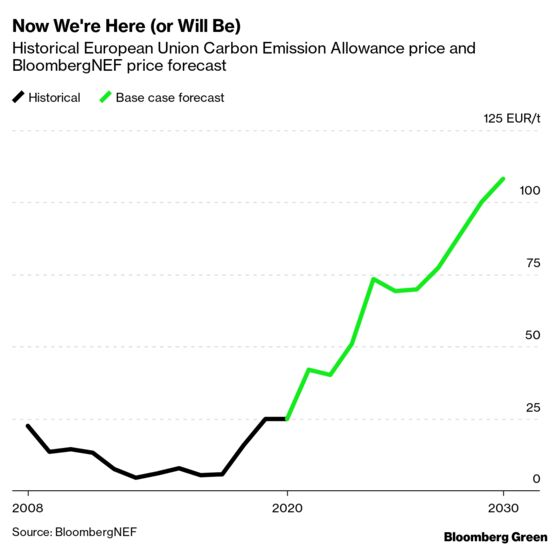

Europe has had a carbon market—the world's first—for more than 15 years. In its first decade, prices did what prices do in a young market filled with uncertainty: They fluctuated.

Traders entering the market in the early 2010s, however, were in for a snooze. For the first half of the last decade, the price of one EU emissions allowance, which represents one ton of carbon emissions, bounced around in a range between four and 10 euros. That’s a low price, in the sense that it cost emitters relatively little and therefore did little to change their behavior.

Today, as the Emissions Trading Scheme looks ahead to its third decade, prices are on the move again. With Europe planning to decarbonize its economies, prices will reach a level by 2030 that a mid-2010s trader couldn’t have possibly imagined.

Let’s look first at the past five years. With the European power sector in particular decreasing its emissions over time, there was ample supply of allowances to meet the demand of big emitters. As a result, prices were low. Since mid-2016, however, allowances have been on a tear, increasing by a factor of 10 from just above 4 euros to 42 euros last month. After years of oversupply, the market is entering a period of expected future scarcity, financial investors are piling in, and prices are rising.

Even higher prices are coming. BloombergNEF expects carbon prices to hit 100 euros by 2030. The reasons why matter for the world’s decarbonization prospects.

In the near term, the U.K.’s exit from the EU (and the emissions trading system) has removed a large, low-carbon power fleet from the market. That means that the average carbon intensity of the remaining EU power generators is higher. At the same time, the number of tradable allowances in the market is being steadily withdrawn into the so-called Market Stability Reserve, reducing supply and putting upward pressure on prices.

In the medium term, we’ll see even more withdrawing of allowances, plus the end of power sector fuel-switching, in which power fleet operators retire higher-emitting fuels such as coal in favor of lower- to zero-emissions options such as gas or renewable energy. Fuel-switching will end for a simple reason, really: There won’t be many higher-emitting plants to switch out of by the middle of the decade.

It’s the longer-term carbon market that’s most interesting—and not just for the carbon market. Last year, BNEF expected the industrial and power sectors covered by the EU carbon market to reduce their emissions by 50% by 2030. It now expects the sectors covered by the EU carbon market to reduce their emissions by 63% in the same period. That deeper decarbonization will be essential to meet Europe’s Green Deal goals. It also means that high-emitting industrial sectors will be forced to act on emissions or pay for the pleasure of emitting.

Where the power sector in particular has been able to decarbonize by fuel-switching, other sectors won’t find it so easy. Switching from coal-fired power to gas-fired power, or from either to renewables, still results in the same product: electrons. Things aren’t so easy for sectors like cement production or chemicals manufacturing, where processes inevitably emit greenhouse gases, with much of those emissions determined by physical and chemical rules.

That is where markets come in, though. While it’s hard to argue with chemistry and physics, it’s not impossible to encourage them to change, so to speak. Markets—and prices—can urge companies to challenge assumptions, test their boundaries, and seek substitutes. As Europe’s carbon price rises, it forces companies to be as emissions-efficient as possible. If the price is sufficiently high, it just might force the entire economy to decarbonize deeply. That will run through two channels: substitution of higher-carbon materials for lower-carbon, and where possible, innovations in production as well. Would either of those ever happen at a carbon price of 10 euros? No. But they just might at 100.

Nathaniel Bullard is BloombergNEF's Chief Content Officer.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.