Syria Shows Risks of U.S. Withdrawal for Europe: Irrelevance

Syria Shows Risks of U.S. Withdrawal for Europe: Irrelevance

(Bloomberg) -- Asked if the European Union hadn’t exposed its impotence during Turkey’s recent military offensive inside Syria, French President Emmanuel Macron was blunt in his response: “I share your outrage.”

More than any other recent foreign policy challenge, the way that Turkey’s “Operation Peace Spring” against the Kurds unfolded has exposed the potential reality of a post-transatlantic world: The EU’s near irrelevance in events that shape security in its own back yard.

“I understood that we were together in NATO, that the U.S. and Turkey were in NATO,” Macron said on Friday after a meeting of EU leaders in Brussels. “And I found out via a tweet that the U.S. had decided to withdraw their troops.”

The EU was absent, too, for the agreement to pause hostilities in Syria in order for the Kurdish allies of the U.S.-led coalition against Islamic State to retreat. Russia, the Syrian government and the U.S. were all involved in some fashion, but not Europe, where administrations were rocked in 2015 by an influx of refugees from Syria’s battlefields.

On Monday, Turkey gave Kurdish fighters until 10 p.m. Tuesday to retreat from a 120-kilometer (75-mile) strip of territory along Syria’s northern border, or face attack when the truce Recep Tayyip Erdogan negotiated with the U.S. expires. That demand appeared to defuse, for now, tension over the wider 444-km “safe zone” that Turkey wants to carve from Kurdish controlled northern Syria.

Macron, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and others have repeatedly urged Europe to do more on its own since Donald Trump entered the White House with a world view that sees no need for alliances, including NATO, and reduces international relations to deal-making and trade balances.

Yet it isn’t clear how Europe could achieve what it calls “strategic autonomy” in practice.

“I appreciate Macron’s frustration,” said Heather Conley, a former U.S. diplomat who heads the Europe program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. “But the simple matter of fact is that Europe cannot substitute for the U.S. militarily, so when that withdrawal happened it changed the calculation for the French troops that were on the ground too.”

Conley was referring to Trump’s initial decision to pull U.S. troops out of the area, effectively giving a green light for Erdogan to move against the Kurdish People’s Protection Units, or YPG, which Turkey considers a terrorist organization.

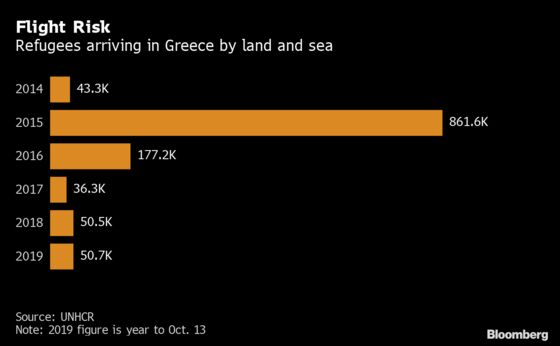

Ahead of Friday’s summit, meanwhile, the EU had struggled even to agree on language to condemn the Turkish military action. Countries such as Hungary worried that Turkey might be provoked into carrying through with a threat to push 3.6 million refugees toward Europe.

A proposed EU arms embargo against Turkey had to be made voluntary to win acceptance.

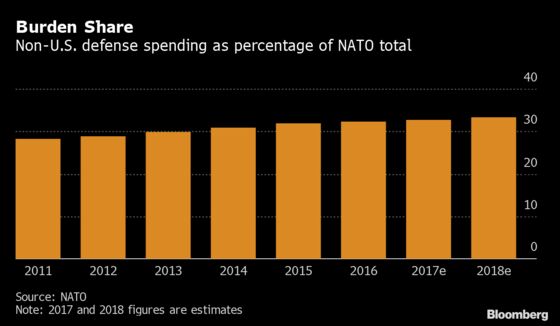

In recent years, France has led the charge to rationalize Europe’s defense spending and build forces that could translate the bloc’s economic heft into strategic strength. Yet only six EU nations – Estonia, Greece, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and the U.K. – met NATO’s 2% of gross domestic product defense spending target in 2018. France fell just shy. The U.S. spent 3.5%.

In 2017, Macron led in creating a new European security program called Pesco, or Permanent Structured Cooperation, which has so far produced 34 joint projects – from the development of an armored infantry fighting vehicle to a cyber rapid reaction force. A European Defense Fund to help pay for these is also being developed.

To address the lack of a European rapid response force, Macron also launched the European Intervention Initiative, which was built outside EU structures and includes the U.K. It’s designed to create a decision-making forum for militarily-capable and willing countries to defend common security interests.

“I believe, and I have so for the past two years, that Europe needs a real autonomy, a real European defense,” Macron said on Friday. “That’s what it means to become a strategic force again.”

Europe does have economic leverage when it is willing to use it. The EU, for example, buys about about half of all Turkish exports. At $85.3 billion worth in 2018, the EU market is almost 10 times as important to Turkey as the U.S., and more than 25 times as large as Russia’s or China’s.

The trouble with all these measures, according to Conley, is that they will at best take years to bear fruit, at a time when dizzying changes in regional security patterns -- including U.S. withdrawal and Turkish realignment away from the West -- are leaving the EU with “an increasingly irrelevant voice” on issues such as Syria. Instability there could hit Europe hard, through returning Islamic State fighters and further waves of refugee migration, she said.

According to a European Parliament report published in June, the EU is collectively the second-biggest military spender in the world, but wastes 26.4 billion euros ($29.5 billion) a year, largely through duplication. The EU operates six times as many different defense systems as the U.S.

The level of waste is even bigger given the EU spends more than half of its budget on staff, compared with 19% on procurement and R&D; the U.S. spends 33% and 29%, respectively.

The Pesco program aims to reduce that duplication and build combat-capable capacity for the bloc to protect its interests without looking first to the U.S. for help. But according to a recent paper from the U.K. parliament, Pesco’s projects are too small to be game changing, “unless the very largest capability projects, such as satellites or combat aircraft, are included in the initiative.”

Asked if they had discussed the question of U.S. reliability at Friday’s summit, Denmark’s Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen said they hadn’t.

“No, we did not and I don’t think we should spend much energy on it,” Frederiksen told reporters. “I think we should spend some energy on the coalition around ISIS, in which the U.S. is the most important partner.”

--With assistance from Lyubov Pronina and Morten Buttler.

To contact the reporters on this story: Marc Champion in London at mchampion7@bloomberg.net;Helene Fouquet in Paris at hfouquet1@bloomberg.net;John Ainger in Brussels at jainger@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rosalind Mathieson at rmathieson3@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.