Strength in Weakness: Why Iran Fights the Way It Does

Strength in Weakness: Why Iran Fights the Way It Does

(Bloomberg) -- Whether eventually it proves a strategic triumph, disaster or just another bloody chapter in Middle East history, U.S. President Donald Trump’s order to kill one of the most senior figures in Iran is exposing the strengths and weaknesses that make the Islamic Republic fight the way it does.

The pinpoint accuracy of Iran’s immediate response to the Jan. 3 killing of Al Quds commander Qassem Soleimani, striking two U.S. bases in Iraq while avoiding causing casualties that could have led to war, has clearly signaled Iran’s capacity to harm American assets and personnel if it chooses -- as well as the limitations on Iran’s freedom to openly do so.

That dilemma in turn appeared to confirm what many military analysts have long assumed: Iran resorts to asymmetric warfare — the use of unconventional weapons and tactics to take on a far greater military might — because it cannot afford to provoke a conventional conflict it would lose.

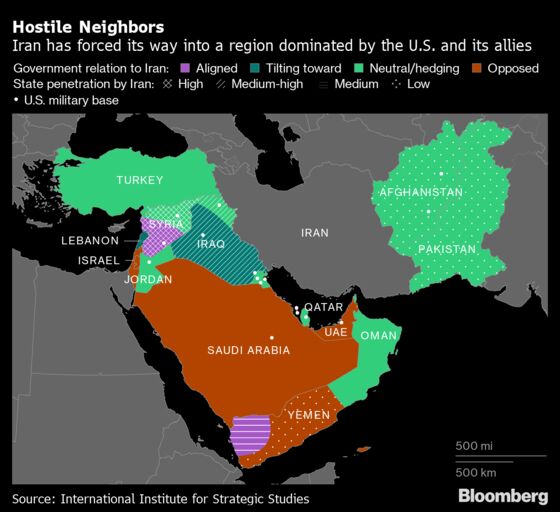

Weaknesses in Iran’s regular air, land and sea forces are the result of decades of economic sanctions and constrained budgets, as the U.S., its Sunni Gulf allies and Israel sought to isolate and weaken the Shiite Islamist regime from its revolutionary birth in 1979.

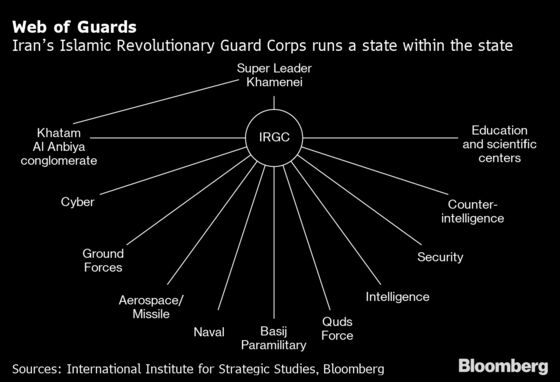

Those shortcomings help explain the prominence achieved by Soleimani’s Al Quds force, a unit of the elite Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps that works with a stable of mainly fellow Shiite proxy militias across the region to challenge the U.S. and its allies.

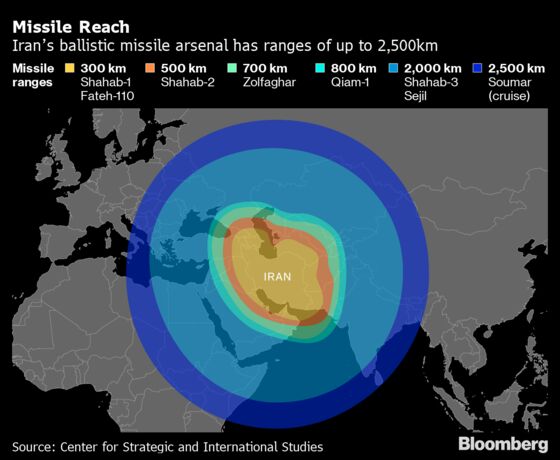

It explains, too, the decision of Iran’s leaders to invest in ballistic missiles, submarines and — most controversially — a nuclear fuel program that could enable Tehran to build atomic weapons, and has propelled the West’s confrontation with the Islamic Republic for much of the past two decades.

The Trump administration is now seeking to rein in all of the asymmetric capabilities Iran has built to compensate for its conventional weakness. Last year, Iran became the first state to have its military forces designated by the U.S. as a terrorist organization.

Iran’s missile response to Soleimani’s killing was an exception, according to Anniseh Bassiri Tabrizi, a research fellow at the Royal United Services Institute, or RUSI, a London security think-tank.

“What you are likely to see now is a reprisal of low-level conflict,” pursued under a cloak of deniability, she said. She recalled a series of attacks on shipping and oil facilities in the Gulf last year for which Iran denied responsibility, as well as more far-flung undeclared operations, such as the 2012 suicide bombing of an Israeli tourist bus in Bulgaria.

Both Washington and Tehran have made it clear that for now they are taking a step back from further military confrontation. But Soleimani’s killing — which followed actions by Iranian proxies in Iraq that killed a U.S. contractor — will leave leaders in Tehran less certain of where the U.S. threshold for escalation now lies.

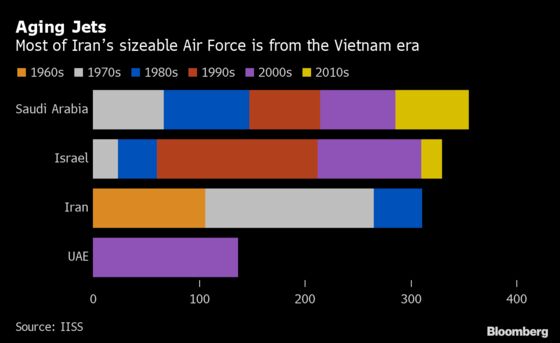

Air Force

For Western militaries, air forces provide a first line of defense and attack. Not so Iran, where decades of sanctions and limited spending power have restricted the purchase of new planes, as well as of spare parts, modern electronics and weaponry.

Iran on paper has 300-plus combat aircraft — more than the U.K. — but the vast majority were bought before the 1979 fall of the Shah and are obsolete, if not grounded. Most, such as Vietnam-era F-4 Phantom IIs and Soviet MiG-29s, couldn’t compete in any contest with the U.S., its Gulf allies, or Israel.

The “slight wild card,” according to Justin Bronk, an aviation specialist also at RUSI, is that Iran claims to have updated versions of the long-range Phoenix air-to-air missiles carried by its 43 F-14 Tomcats, a plane retired by the U.S. Navy in 2006. Though a limited resource, that could make them able to stand back while putting an opponent at risk.

Ground Forces

Iran’s regular army, at 350,000, is considerable, especially once you add the IRGC’s 100,000 ground troops. Yet it has been starved of investment, especially since the U.S. toppled Saddam Hussein in Iraq in 2003, removing the only credible threat of a ground invasion across Iran’s expansive and difficult terrain. Iranian analysts, like those abroad, believe any eventual U.S. attack would come from the air. As Saddam discovered, aging battle tanks and artillery are just target practice for an adversary that establishes air superiority.

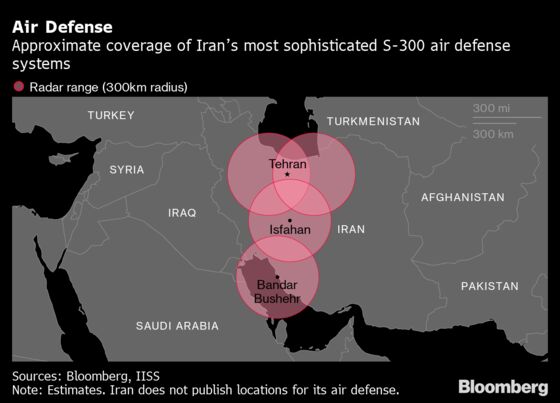

Air Defense

After more than a decade of trying to buy highly capable S-300 anti-aircraft systems from Russia, Iran received its first shipments in 2016 and now has 32 launchers, organized in groups of eight around four 300-kilometer radars. Yet this number falls far short of the blanket protection Iran would want.

While the Iranian military also deploys an impressive array of other surface-to-air systems, many are old and pose little threat to new generation aircraft. The capabilities of domestically made or upgraded systems are largely unknown. Adding to this patchwork effect is that air defense networks are complex, combining layers of systems to defend against anything from high-altitude bombers to low-flying cruise missiles and helicopters. These need to be fully integrated to work efficiently, but in Iran responsibility is split between the regular armed forces and the IRGC.

The accidental downing of Ukrainian International Airlines Flight 752 on Jan. 8, killing all 176 on board, could be in part a product of this lack of a fully integrated air defense. The Russian-made TOR-M1 launcher used against the airliner was a mobile system under the control of the IRGC, and not hardwired into wider communications and radar networks under regular army control, creating more scope for error.

“The command and control process in the Iranian military is often tangled and overlapping, and that’s especially problematic for air defense,” says Henry Boyd, research fellow for defense and military analysis at the International Institute for Strategic Studies.

Navy

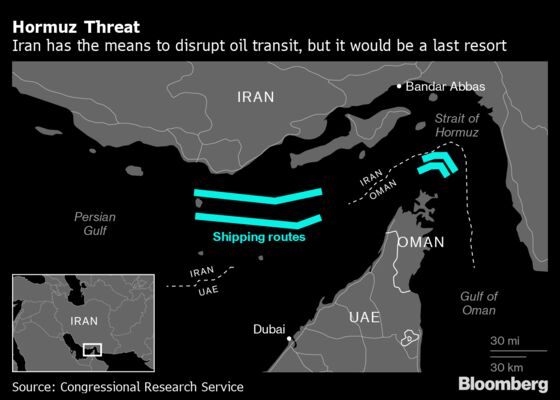

Iran’s navy is similarly split between the regular armed forces and the IRGC, with the latter having full control of assets in the Gulf. Unable to buy or build cruisers and destroyers to compete with U.S. 5th Fleet, Iran has again looked for low cost ways of leveling the battlefield. It has invested in underwater mines, submarines, and about 200 small speed boats armed with missiles and designed to swarm a potential enemy. That might be enough to close the Strait of Hormuz, the world’s foremost chokepoint for oil shipping, for a time but doing so would represent a nuclear option for Iran.

More than the U.S., Saudi Arabia or the United Arab Emirates, closing the route would damage Iran’s biggest trade and investment partner, China, as well as friendly Gulf States such as Qatar and Oman. The U.S. now relies less on Gulf oil imports than China, which gets more that 40% of its crude via the strait; the Saudis and Emiratis can pipe oil out by land if need be. Closure could also invite the massive retaliation Iran seeks to avoid, making it valuable mainly as a threat that Iran’s mini-navy is there to make.

Ballistic Missiles

Iran has developed a cheaper tool to perform many of the functions of an air force: surface-launched missiles. Had the U.S., for example, wanted to carry out a similar precision strike to the one Iran made in Iraq earlier this month after Soleimani’s killing, it probably would have used a combination of attack aircraft and cruise missiles, according to Boyd at the IISS.

Iran used its suite of land-based ballistic missiles, and not for the first time. In 2017, it launched six surface-to-surface missiles against Islamic State positions in Syria, retaliating against attacks by the extremist group in Tehran. In 2018, it struck the Iraq bases of Kurdish groups running insurgencies in Iran. Proliferation to proxies in Lebanon, Yemen and Iraq has allowed Iran to attack Saudi Arabia, Israel and the U.S. at arm’s length. The missiles by now also form Iran’s most important deterrent, creating a retaliatory threat from southeastern Europe to India, an area that’s home to more than 70,000 U.S. troops.

The Revolutionary Guard and Its Proxies

The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps remains the bedrock of the Iranian leadership’s defense — more ideologically aligned, and better equipped and trained than the regular army. It also has huge commercial and financial interests embedded in the economy.

Abroad, the network of proxies that Soleimani operated, from Hezbollah in Lebanon to Kataeb Hezbollah in Iraq, remains one of the most potent, deniable and therefore usable weapons in Iran’s armory. Deploying affiliates carries two other advantages: they are cheaper to operate and any casualties incurred are less likely to stir anger at home. The new Al Quds commander was Soleimani’s deputy and has pledged to continue his strategy unchanged. It remains to be seen whether he can maintain the same level of control.

Cyber

Iran is widely seen to have become serious about its cyber-security program only after the 2010 Stuxnet virus attack attributed to the U.S. and Israel, which infected controllers for centrifuges used in Iran’s uranium enrichment program, tearing them apart. Iran’s cyber capabilities have lately become a major focus for discussion, as their low profile and deniability make them a potentially ideal weapon for striking back at the U.S. over the long term. However, for now, Iran isn’t considered to pose the same level of cyber threat as Russia, China, or even North Korea.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Mark Williams at mwilliams108@bloomberg.net, Karl Maier

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.