Stock Market Strains Send Message the Fed Doesn't Want to Hear

Signs of Fed-fomented stress are everywhere, from slumping bank stocks to the 33 percent plunge in home builders since January.

(Bloomberg) -- Donald Trump loves to bash Jerome Powell, blaming him for the market meltdown. And while people can debate if the hectoring is a good idea and whether the Federal Reserve cares about stocks, it’s getting harder to argue the president is totally wrong.

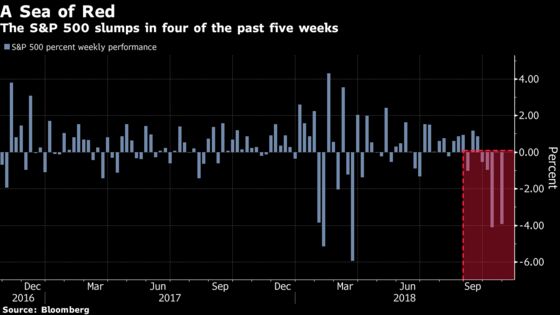

Signs of Fed-fomented stress are everywhere, from slumping bank stocks to the 33 percent plunge in home builders since January. They’re in the market’s newfound willingness to differentiate between defensive and cyclical stocks, a bias absent from past meltdowns. They’re in the giant yawn greeting stellar earnings, evidence investors have something else on their mind.

The fundamentals are strong, goes the refrain, and the economy can absorb some tightening. But with eight rate hikes in the book already and more to come, it’s obvious many investors are feeling otherwise.

“This sell-off shows that the markets are pricing in slower growth and more risk,” said Ilya Feygin, senior strategist at WallachBeth Capital LLC. “The Fed may not necessarily see that.”

Whether or not they see it, policy makers say they don’t mind it. Up and down volatility “is typical” of stocks, Fed Bank of Dallas President Robert Kaplan said Friday during an interview on Bloomberg Television. A day earlier, Cleveland Fed chief Loretta Mester said “we are far” from the turbulence that would lead to a big pullback in spending.

The Volatility Ramp: Bloomberg Reporters Talk Markets

“I don’t think they’re nervous now,” said Roberto Perli, a partner at Cornerstone Macro LLC in Washington and a former Fed economist. “Their view is that stocks went up a lot the past many years, and adjustment at some point is going to happen.”

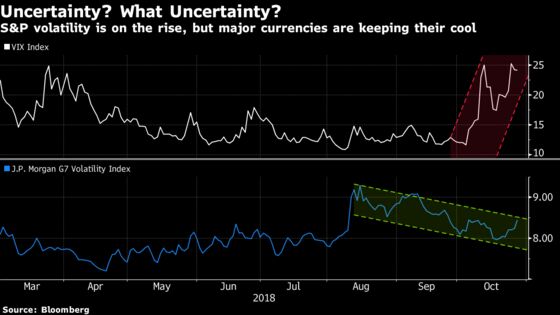

None of that helps if you’ve watched $10 trillion lopped from U.S. equity prices in a month, even as bonds and currency remained calm. And while stocks are clearly their own animal, all hair-trigger volatility and bloated valuations, the possibility they are acting as a warning signal for the rest of the economy shouldn’t be discounted.

The most straightforward evidence that tighter conditions are at the center of the tempest is in rate-sensitive groups like homebuilders and banks. Building companies have tumbled in nine of the past 10 weeks as higher borrowing costs contributed to disappointing housing data. Banks, normally beneficiaries of higher rates, have slumped 15 percent on concern rising financing costs have crimped loans.

A related sign is the brighter distinctions investors are making among sectors, favoring those with less exposure to the economy. While February’s sell-off crushed everything, this time defensive sectors are holding up. It’s a sign to some that investors are adjusting their stance on the path of expansion.

“Certainly interest rates are impacting the economy, I don’t think there’s any doubt about that," Peter Jankovskis, co-chief investment officer at Oakbrook Investments. “It makes perfect sense in the context of what’s happening in the economy that those particular industries have been hard hit in this market.”

The rotation was on display on Wednesday, when consumer discretionary firms, the top gainers of the bull market, trailed consumer staples by the most since 2009. Utilities, one of the least crowded groups in the S&P, outperformed industrials by the most since the financial crisis. The trend is here to stay, according to Aidan Garrib.

For the week, consumer discretionary stocks slid 1.4 percent, pushing the S&P 500 toward a 3.9 percent slump. The Dow Jones fell 3 percent and the Cboe Volatility Index rose to 24.40 after closing above 25 on Wednesday for the first time since the February rout.

A more abstract concern relates to the reception corporate earnings received this season. In short, there wasn’t one. Companies that beat estimates didn’t rise, and companies that didn’t fell only moderately. Correlations, which usually loosen as corporate results cause individual stocks to chart their own course, never unwound, and in fact got tighter as the month progressed.

It smacks to some of a market with more pressing concerns.

“One interpretation of this is that the stock market is correctly anticipating weakness in earnings and in the economy going forward,” said Ethan Harris, head of global economics at Bank of America. “When the Fed goes into a tightening cycle, which we’ve been in for the past two years of consistent movements, investors don’t expect this to be painless.”

Is any of this likely to matter to the Fed? Investors surveyed by Bank of America think the S&P would need to fall to 2,500 or lower to alter its pace. That means the strike price on any so-called Powell put would require further downside of at least 6 percent.

At the same time, bond traders are now barely pricing in two rate hikes between year-end 2018 and year-end 2020, eurodollar futures data show. The Fed projections, released a month ago with stocks near records, call for twice as many over that period.

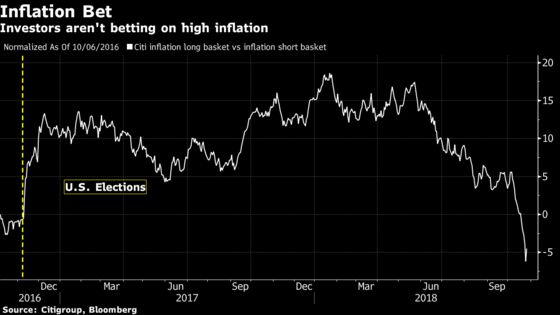

While signs abound that investors are paying a price for Fed hawkishness, other parts of the market are saying the hawkishness is misplaced. Indexes compiled by Citigroup group stocks by whether they do well or badly when inflation rises. Right now, the ones that do well are plunging, arguably a sign the market doesn’t think there’s much inflation to fight.

Volatility in major developed-nation currencies remains well below its highs for the year, according to a JPMorgan Chase & Co. gauge. In the government bond market, 10-year Treasury yields just had their biggest weekly decline in two years. An indicator that plots expectations for price pressures in that market by via rates on inflation-protected bonds is starting to show that Fed policy is becoming too tight.

Government reports don’t show the economy overheating. Existing home sales fell to the lowest since 2015, core inflation is steady near the Fed’s goal, and manufacturers’ new orders were below expectations. That doesn’t signal a recession is looming, according Neil Dutta, Renassaince Macro Research head of U.S. Economics. Rather, weakening data signals that that the pace of further rate hikes should be consistent with the economic conditions.

“They’ve weaned the markets off of forward guidance, which implicitly means that data is going to drive the boat,” Dutta said on Bloomberg Television. “So lets focus on the data! I don’t think inflation is going to go back to like 1 percent or something like that on a year over year basis, but is it going to accelerate? I am skeptical of that, and remember, that’s what the Fed has in its forecast.”

--With assistance from Katherine Greifeld, Sarah Ponczek, Vildana Hajric and Lu Wang.

To contact the reporter on this story: Elena Popina in New York at epopina@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Chris Nagi at chrisnagi@bloomberg.net, Jeremy Herron

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.