Steeper Yield Curve Proves No Boon for Banks in Zero-Rates World

Steeper Yield Curve Proves No Boon for Banks in Zero-Rates World

(Bloomberg) -- The Treasury yield curve has steepened this year, offering some relief for banks that borrow cheaply in the short term and lend in the long term. At least that’s what the finance textbooks say.

In reality, the benefits for banks have diminished the closer rates get to zero. That runs against recent optimism from some fund managers and traders that earnings would be aided by a wider gap between short-term and long-term interest rates.

What’s more important to banks is how far rates are above zero. The higher the rates, the bigger the spreads charged on loans. Large lenders like Bank of America Corp. and JPMorgan Chase & Co. benefit more when short-term rates are high -- even if that means a flat or inverted curve -- because most loans are priced at spreads to Libor or similar short-term benchmarks.

“The problem is we’ve had very low rates for a very long time now,” said Moorad Choudhry, author of more than a dozen books on finance. “The existential crisis for many banks is the very, very low interest rates.”

With the Fed slashing rates to near zero and signaling they will remain there until at least the end of 2023, yields on government debt with up to five years to maturity have been pinned. Yields on five-year Treasuries hover near the top of the central bank’s zero to 0.25% target range and those on securities with less time to maturity are even lower. Traders see this yield regime remaining for the foreseeable future, given that Fed Chair Jerome Powell has said the central bank is “not even thinking about thinking about raising rates.”

The KBW Bank Index is down about 25% since the fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic forced the first of two Fed rate cuts in early March. It’s 37% lower for the year, while the S&P 500 is up about 2.6% in 2020.

While the front of the yield curve is very flat, the Fed has been foreshadowing a move to a monetary policy framework that allows inflation to run hot for some period of time. That has been steepening the curve beyond five years. The gap between 5- and 30-year yields in June reached its steepest in almost four years and is not far from those levels now - trading at about 116 basis points.

The Fed followed through and last week fully locked in the new policy.

Mortgages

Thirty-year mortgage rates do follow yields on Treasuries of the same tenor, however U.S. banks don’t typically hold many mortgages on their balance sheets. They make fees on them and sell most of them to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The government-backed finance companies then package them into mortgage-backed securities, which are sold to investors worldwide. U.S. banks buy some of those securities, but the amount of MBS on their balance sheets is very small relative to other assets.

Meanwhile, most corporate and consumer loan rates are based on benchmarks such as Libor or its intended replacement -- the secured overnight financing rate. Banks would typically charge a spread over three-month Libor for a five-year loan, yet they’re forced to reduce that spread as rates decline. Regardless of where Libor is, there’s a psychological barrier that prevents customers from accepting a 3% loan rate when short-term rates hover at 0% even though they didn’t balk at 6% loans when short-term rates were 3%.

“Theoretically, at low rates you can get the same spread as a bank,” said Brendan Browne, an analyst at S&P Global Ratings. “But in reality, as rates go so low, then you can’t charge the same spread. Spreads come down as rates get close to zero.”

That’s why banks’ interest income relies more on how high rates are than the curve’s steepness. A steeper curve helps on the margins because of the MBS portfolios, but its impact is limited.

BofA, JPMorgan Chase

Bank of America Corp., which has the biggest holdings of MBS among U.S. banks, said its net interest income would rise by $3.3 billion a year if long-term rates rose by 1 percentage point, without a change to short-term rates. Yet the bank’s interest income would surge by $8.8 billion if both short- and long-term rates went up by the same amount. And even a flatter curve -- the short-end moving up by 1 percentage point while the long-end stays the same -- would be more beneficial than a steep curve close to zero, boosting its interest income by $5.5 billion. That’s because its $348 billion MBS portfolio pales in comparison to the $1 trillion loan book.

JPMorgan Chase & Co., in its latest quarterly filing, said a steeper yield curve would boost interest income by $1.7 billion while a flatter one would lead to a $2 billion increase.

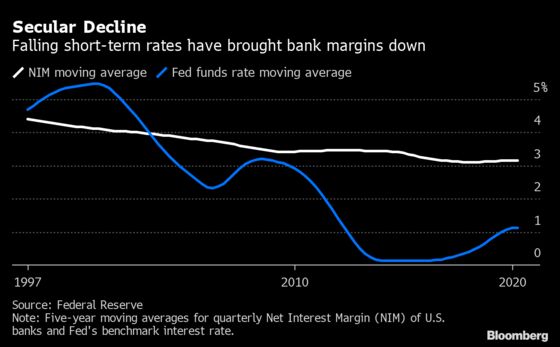

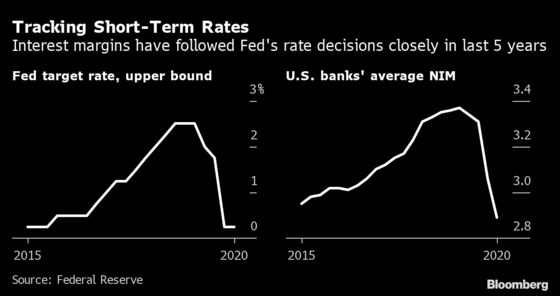

This explains why U.S. banks’ net interest margin has consistently declined in the last three decades as rates have fallen. The peak NIM for the past five years occurred when the curve was actually inverted in 2019 as the Fed’s rate increases pushed short-term rates to 2.5%. That was the first inversion, which has historically flagged a recession coming in 12 to 18 months, since 2007. Of course, a recession ultimately is bad for banks because their loan losses jump during a downturn when consumers and companies can’t pay their debts.

Other wrinkles in the equation for bank profits include a decades-long shift away from interest to fee income, along with hedging more of their interest rate risks. Both have made their earnings less sensitive to rate moves.

As the pandemic-induced recession cost U.S. banks billions of dollars in loan losses in the first half of this year, fee income was a savior. The largest firms have been propped up by trading revenue as surging market volatility helped that business. Smaller banks could reap the benefit of rising mortgage origination fees as falling rates lead to a re-financing boom. The largest banks’ net interest income was roughly the same as their fee income in the first half. The ratio was a bit lower for the regional banks, but not that far off.

“Banks have worked to protect themselves and manage the risks of changes in the yield curve,” said James McAndrews, a former Fed research director. “They have lived in an environment of a relatively flat yield curve for years and they are quite well-situated to withstand movement in the yield curve.”

Downtrodden shares of European banks, which have struggled with ultra-low and even negative interest rates for years, provide a cautionary tale. While U.S. lenders as a group may be in a better position to weather the environment, analysts still caution that headwinds won’t abate until rates are rising again.

“Of course the best of both worlds is higher absolute level of short-term rates and a steep curve,” said Brian Kleinhanzl, an analyst at Keefe, Bruyette & Woods. “But we haven’t seen that ideal scenario since 2005. The continuing low-rate environment we’re in now is a slow grind on bank profits over time.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.