Why Is a Drug Banned in Europe, Canada Still Being Fed to U.S. Pork?

Stalemate at FDA Puts Pork With Toxic Risk in U.S. Food Supply

(Bloomberg) -- America’s hog farmers have been fattening up their pigs with an antibiotic added into animal feed that was deemed safe for nearly four decades. Then six years ago, regulators realized they might be wrong — and that cancer-causing chemicals could be making their way to consumers through pork chops and hot dogs.

With the threat of dangerous carcinogens entering the food supply, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration decided it would yank approval for the drug, called carbadox. But then, the agency quickly backed down.

At every junction, the drug’s maker, Phibro Animal Health Corp., has battled to keep selling carbadox. And so far, the FDA keeps conceding.

Carbadox is banned in Canada and Europe. But a huge share of pork products in the U.S. are made with the stuff, and it’s used by 90% of American feed producers today. As the saga drags on, the FDA will once again consider the safety of the product at a public hearing on March 10. Phibro is expected to sustain its fight to keep carbadox alive.

“It’s frustrating,” said Steven Roach, safe and healthy food program director at the nonprofit Food Animal Concerns Trust. “Even after they decided to withdraw it, almost six years later, it’s still on the market — people are still exposed to residues.”

“We shouldn’t intentionally be adding carcinogens to our food,” he said.

In an emailed response to questions from Bloomberg News, Phibro Chief Financial Officer Damian Finio said that the company “can ensure consumers that no residues of carcinogenic concern can be detected at the end” of the 42-day period that is required between giving a hog carbadox and when it is slaughtered.

Drawn-Out Battles

Consumers the world over are rethinking what they eat, sending demand surging for foods that are organic, free-range and pasture-raised. Meat, and what gets fed to livestock, has come under particular scrutiny, with even companies like McDonald’s Corp. pledging to move toward more antibiotic-free proteins. And while regulators in other countries, especially in Europe, have applied closer inspection to what they’ll allow to market, the FDA has sometimes failed to keep pace.

The agency has a history of getting tangled in long, drawn-out battles to get potentially dangerous animal drugs off the market. In the early 2000s, new research raised questions about an antibiotic used on chickens that contained arsenic, also a carcinogen. The FDA did some limited research that prompted Pfizer Inc. to stop selling one of the arsenic-containing drugs, roxarsone, in 2011, but the last of the arsenic-containing antibiotics didn’t come off the market until 2016.

“It’s often the case that action on animal drugs takes longer than it should,” said Keeve Nachman, director of the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future’s Food Production and Public Health Program. Nachman did extensive research on roxarsone.

Carbadox is also used to treat certain animal diseases, but the marketing brochure Phibro posts online is largely focused on weight gain. It touts a study that found pigs fed the drug were as much as 10 pounds heavier than ones that weren’t, depending on the dose.

The drug first won U.S. approval in 1972, when it was being produced by Pfizer, according to FDA documents. In 2000, Pfizer sold its animal-feed business to Phibro, which in turn took control of carbadox. The antibiotic, marketed under the brand name Mecadox, is sold in bags of tiny yellow crystals that are added to pig feed.

An exemption in U.S. law allows for cancer-causing drugs to be used to grow livestock as long as harmful residues can’t be passed from animal to human. The clause was named the DES Proviso after one of the drugs that was approved because of it, diethylstilbestrol. DES itself was later pulled from market in the 1970s after an increasing number of cows tested positive for carcinogenic residues. That ban, too, came only after another long battle with the industry.

Carbadox has benefitted from the DES Proviso for years.

Data presented in the early 2000s to an international committee that advises the World Health Organization and the United Nations showed that the testing method used to make the assumption that nothing carcinogenic would remain in the tissue of pigs was flawed. That prompted the international committee to declare there is no safe level of carbadox in feed use. The European Union and Canada had already banned carbadox simply because it was carcinogenic, even before it was revealed that the residue-testing method was inaccurate.

After the international committee’s findings, the FDA asked for data and information from Phibro, “which did take time to generate,” Veronika Pfaeffle, a spokeswoman, for the agency said.

In 2016, the agency finally gave notice it wanted to withdraw carbadox approval after a year of calls and meetings with the company hadn’t produced anything that would prove the drug is safe.

The FDA said at the time it had found “there could be potential risk to human health from ingesting pork” from animals treated with carbadox, adding that removing the product from the market would reduce lifetime cancer risk to consumers, according to a 2016 statement.

Rising Sales

Six years later, carbadox is still on the market. In that time, its sales have risen by 57% to $22 million in the year ending Dec. 31, according to Phibro filings.

Phibro says the data it provided to the FDA proves carbadox is safe. The company has also submitted an alternative test method for agency consideration, according to CFO Finio.

The company also often notes that carbadox isn’t used in humans, and therefore is important in efforts to prevent antibiotic resistance. The National Pork Producers Council made this argument in comments in September 2020 to the FDA and again in response to questions from Bloomberg News.

In July 2020, the FDA said that after the years of back and forth with Phibro, the company “failed to establish that carbadox is safe for use under the approved conditions.” At the same time, the agency filed a new notice saying it planned to revoke approval for the method Phibro used to test for the carcinogenic residues. Phibro once again challenged the agency, and this month’s FDA hearing comes more than a year and a half later.

If the testing method is finally revoked, the FDA said only then would it file a notice that it plans to withdraw approval of carbadox, likely setting off another months- or even years-long process to remove the drug from the market. Going after the testing method, the FDA determined, “is the most straightforward and least resource-intensive process for removing carbadox from the market,” the agency’s Pfaeffle said.

Phibro plans to continue its fight.

“In the event that, following the hearing, the FDA continues to assert that carbadox should be removed from the market, we will argue that we are entitled to and expect to have a full evidentiary hearing on the merits before an administrative law judge,” Phibro said in its financial report for the quarter ending Dec. 31.

Fatter Pigs

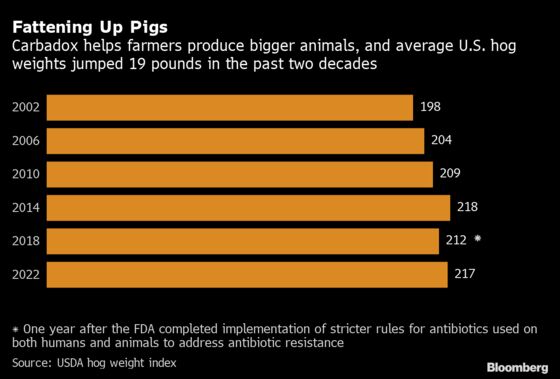

Carbadox’s use for animal weight gain has been in line with the direction of America’s hog industry.

“Bottom line, Mecadox can help you market more pork,” Phibro’s marketing brochure states, referring to the brand name.

American pork production has boomed in recent decades to keep pace with demand for exports. Pigs have grown to enormous sizes, allowing farmers to make more money per animal. The average U.S. hog weight has ballooned to about 216 pounds (98 kilograms), or roughly 10 pounds more than the 20-year average.

Carbadox sales have been so robust that Phibro announced in 2019 it completed a new, dedicated manufacturing operation to produce more of the drug.

Michael Hansen, a senior staff scientist at Consumer Reports, said he’s frustrated carbadox has grown in popularity while it’s been under this cloud.

“It’s like c’mon, they’ve known this for 20 years and done nothing about it,” he said.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.