Sparklines: Don’t Look for Disruption in a Porsche

Sparklines: Don’t Look for Disruption in a Porsche

In climate news today…

- Global temperatures are poised to break another heat record.

- Most of the U.K.’s banks and insurers are unprepared for climate risk.

- A leading environmental group is moving into sustainable finance.

- Texas and Iowa last year installed more wind turbines than ever.

(Bloomberg) -- Don’t look for disruption in a Porsche.

Global car production declined last year—and might not grow at all for another five years, according to an analysis by Robert Bosch GmbH, one of the world’s leading parts suppliers. At the same time, the internal combustion engine is undergoing a pincer attack, with the top end of German luxury sedans going electric on one side and the humble scooter getting more sophisticated on the other.

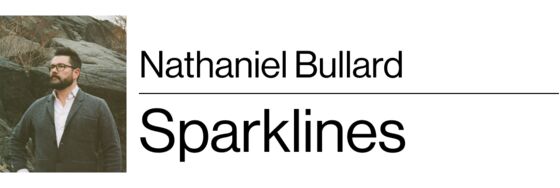

First, those German luxury sedans. Porsche AG had another year of record sales in 2019, as more than 280,000 buyers picked up its vehicles last year. Regular readers will know my enthusiasm for Porsche sales reports as an indicator for what well-heeled buyers want (mostly: SUVs). Last year, sales broke down to about one-third smaller SUVs (the Macan), one-third larger SUVs (The Cayenne), and one-third everything else (sedans, coupes, and supercars).

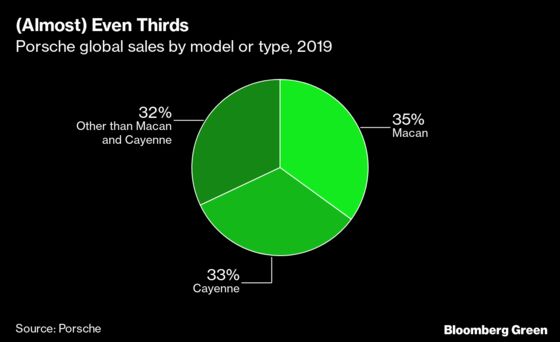

In North America, Porsche had its tenth consecutive year of growth. After two years in which its SUV share of total purchases slipped, sales of the new Cayenne model soared, and now the company sells more SUVs than ever in the region.

There’s something to notice on top of that SUV trend, though, in my chart above: Porsche sold 130 of its all-electric Taycan sedans in December. More interesting than that number, though, is who it represents.

In a Bloomberg TV interview last week, Porsche North America boss Klaus Zellmer said that “Fifty percent [of Taycan buyers] are new to the brand, so they have never owned a Porsche before. A conquest rate of 50% or more is a very good indication of having the right strategy, in our business model at least”.

What were those 50% of buyers going to buy if they didn’t buy a Porsche? It seems reasonable that some would buy a Model S, Tesla Inc’s flagship model, or perhaps a BMW 7-series, a Mercedes S-class, or an Audi A8 sedan. Perhaps some are coming in from sportscar territory—or perhaps not. As Bloomberg reported last year, the majority of Tesla’s Model 3 buyers are trading up from less expensive cars. Porsche’s well-reviewed presence could shake up the top end of the luxury sedan market, and perhaps even expand it.

I’m just as interested, though, in what’s happening at the entire other end of the global market for moving people around. Earlier this month, Skip Scooters published a lifecycle analysis of its new scooter models, noting 5- to 20-fold improvements in how often some scooter components need replacement. It’s made those improvements by custom-designing its latest model, rather than using “readily available and inexpensive”, but easily broken, consumer scooter models.

Clayton Christensen, the giant of business strategy who passed away this week, gave us a framework for thinking of technologies that seem inferior at first but result in new and major markets. Disruptive innovation, as Christensen called it, became such an influential idea that seemingly every company today has either a strategy for disruption, or a strategy for avoiding being disrupted.

Both electric Porsches and electric scooters fit different parts of Christensen’s theory. Porsche, one of the “established companies,” is a natural leader in “developing and commercializing new technologies … as long as those technologies address the next-generation performance needs of their customers.” Scooters, meanwhile, are “in the forefront of commercializing new technologies that don’t immediately meet the needs of mainstream companies and appeal only to small or emerging markets.”

An electric Porsche, with half of its buyers new to the brand, suggests that there’s an audience to play for at the top end of the auto market. That’s a business of experiences, refinement, brands and reputations. Porsche and its peers may electrify that segment, but they’re not going to be disruptive about it.

For that, Christensen’s work tells us to look at the bottom end where products are initially inferior, where incumbents generally ignore emerging opportunities, and where margins are low. There’s much in play at the bottom end of mobility, as well. That’s a business of moving people and things, at cost, conveniently, in ways that adapt and evolve quickly. It’s also where the real disruption lies.

What else you need to know in Green

Where to Invest $1 Million Right Now Five experts offer investment ideas that help fight climate change.

Big Central Banks Are Getting Louder on Climate Some of them are even starting to do something about it.

Electric Ferries Will Fight Bangkok’s Toxic Smog The next electric vehicles will ply Thailand’s waterways, not highways.

A Flight-Shame Cure in Jet Fuel Made From Water? Germany looks to green kerosene.

Arbitrage Won’t Stop Climate Change Kate Mackenzie argues that benefits of environmental investing can’t last.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jillian Goodman at jgoodman74@bloomberg.net, Adam Blenford

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.