Facing Drought, Southern California Has More Water Than Ever

Facing Drought, Southern California Has More Water Than Ever

(Bloomberg) -- The cracked and desiccated shoreline of Lake Mendocino made a telling backdrop for California Governor Gavin Newsom’s message at a news conference last week: Drought conditions are here, and climate change makes the situation graver.

But water supplies vary across regions, which is why the governor limited a drought emergency declaration to just two northern counties. In fact, highly urbanized Southern California has a record 3.2 million acre-feet of water in reserve, enough to quench the population’s needs this year and into the next.

That’s thanks in large part to tremendous gains in storage infrastructure and steady declines in water use — driven by mandates, messaging, and incentive programs — belied by the region’s storied reputation for thirst.

Brad Coffey leads water resource management at the Metropolitan Water District, the wholesale water cooperative that serves about half the state’s population via 26 member agencies in Southern California. Talking about the state’s drought cycles, he invoked John Steinbeck, who once wrote: “It never failed that during the dry years the people forgot about the rich years, and during the wet years they lost all memory of the dry years.”

“Our job is to not lose memory of the dry years,” Coffey said. “And we’ve planned for them.”

Since the early 2000s, the region has invested more than $1 billion in new storage infrastructure, including a nearly trillion-liter reservoir at Diamond Valley Lake and the Inland Feeder Pipeline, a 44-mile network of tunnels and pipes that more than doubled capacity for deliveries from the State Water Project, California’s massive system for water storage and delivery that serves many its cities.

These, as well as expansions in groundwater storage, allow more resources to be stashed during flush years like 2017, when a record-wet winter dumped more than 100 inches of precipitation on the Sierra Nevada mountains and prompted the official end of California’s last drought. Conditions held in 2019, producing spectacular “superbloom” displays that drew flower-peepers from around the world.

Now snowpack in the Sierra Nevada is about 40% below average levels, and allocations from the State Water Project have been cut to just 5% of requested supplies. The return of dry conditions — for the second year in a row — brings a sense of déja vu from just a few years ago.

But the last drought triggered changes in how Californians consume their precious resource. At the press conference last week, Newsom praised the 16% reduction in water use the state has made since 2013.

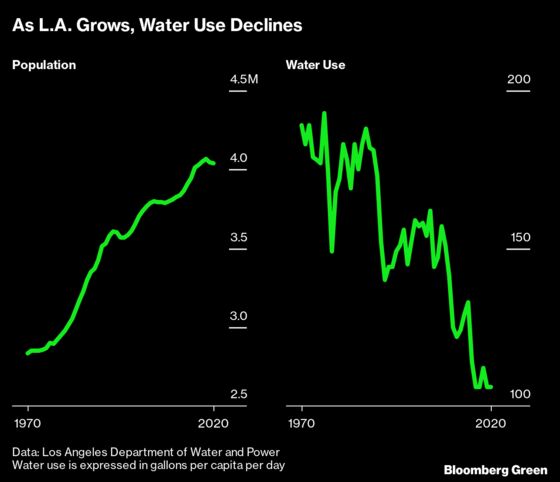

Southern California has been a leader in that trend. L.A. now uses less water now than it did in the 1970s, despite adding 1 million residents. While total and per capita water use crept up in the early 2000s, the 2012–16 drought set off another major drop in demand. That’s because state conservation mandates, intense media coverage and city-sponsored incentives for lawn tear outs and low-flow fixtures spurred changes in household behavior.

Gone are L.A.’s days of dribbling sprinkler heads and hosing down driveways, both banned under city ordinance. Since 2009, nearly 52 million square feet of lawn have been replaced through rebates and outreach programs boosting drought-tolerant succulents, flowers and chaparrals. Even the iconic grassy expanse that fronts Westwood’s Mormon Temple is now edged with low-water plants (though there’s still a lot of grass).

In other words, the land of swimming pools, lush backyards and the historic thirst for growth that inspired the movie Chinatown has seen its conservation ethic outlast previous droughts.

“On the conservation side, we never lifted the foot off the pedal, which helps the region and city get into a good place with respect to the dry years we’ve had before and are having again,” said Delon Kwan, assistant director of water resources at the L.A. Department of Water and Power. “There’s a very direct correlation between demand going down and reserves going up.”

Investments in water recycling, desalination and stormwater capture have also made a difference. The city does not expect to ask residents to ration supplies this year or the next, Kwan said.

Such efforts have won praise — though with caveats — from water policy experts like Newsha Ajami, the director of urban water policy at Stanford University's Water in the West program.

“People often focus on southern California as a group that uses a lot of water and is unsustainable, and some of that is true,” she said, comparing the 106 gallons per capita per day used in Los Angeles in 2020 to the 72 gpcd used in San Francisco, where greater density means a lot less outdoor landscaping. (Ajami sits on the S.F. Public Utilities Commission, the city’s water agency.) Because population outweighs local water resources, L.A. and other nearby cities rely heavily on imports from the Sierra Nevada and Colorado River — a system that stems from early 20th-century water rights agreements and feats of human engineering.

Yet the recent storage expansion in the south is unmatched in the historically wetter north, Ajami said. “They’ve done a lot more to diversify and save water compared to some other communities across the state,” she said. “It shows that when you're under constant stress, you respond.”

That doesn’t mean Northern California has neglected to store and conserve. But many communities that depend more on local rainfall — rather than state and federal water systems — are facing rationing this year. In Marin County, the Marin Municipal Water District has mandated limits on outdoor watering, car washing, and other water-intensive activities for its 191,000 customers, as have the towns of St. Helena and Calistoga in neighboring Napa County. The city of San Francisco plans to ask irrigation customers — such as parks and golf courses — to voluntarily cut use 10%.

Meanwhile, thousands of California farmers are expecting to receive tiny fractions of needed supplies as they face forecasts for an intensely hot, dry summer with elevated wildfire risk. Environmentalists are sounding alarms about threats to the vulnerable species and ecosystems that rely on the same precious flows that feed agricultural and urban supplies throughout the state. As climate change brings higher temperatures, longer droughts, and more conflicts over those resources, they are set to dwindle, and with them, California’s potential supplies.

That’s why L.A. hopes to wean itself off of imports and expand its capacity for self-sustenance. Mayor Eric Garcetti has pledged to source 70% of the city’s water locally by 2035, while L.A.’s latest urban water management plan calls to reduce per capita water use to 100 gpcd by 2035.

Going beyond that would require a majority of customers to stop watering yards, which makes up the majority of L.A.’s water use, Kwan said, and may not be cost-effective. Still, many researchers say L.A. should aim higher. A recent UCLA sustainability report called for L.A. to set a goal of 75 gpcd.

“Demand management is the best and cheapest way we can approach water security,” Ajami said. “There is no supply in California that is not vulnerable.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.