Why Sioux Falls Is Booming

South Dakota’s biggest city isn’t a college town or a state capital or in the Sun Belt. So how does it keep growing and growing?

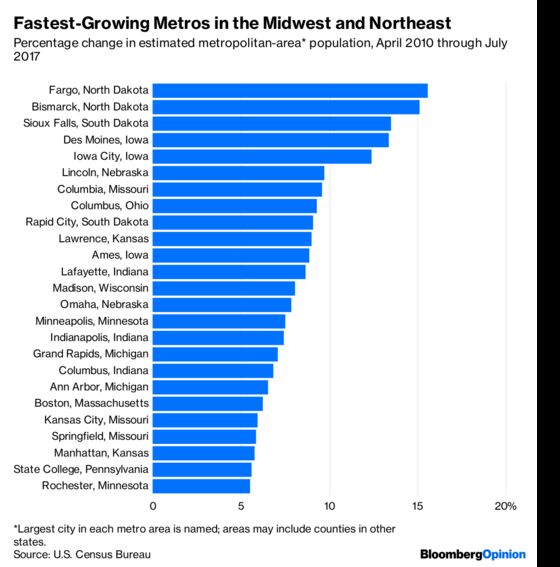

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- There are 63 metropolitan areas in the U.S. (out of 382 total) that saw their populations grow by 10 percent or more from 2010 through mid-2017, according to estimates compiled by the Census Bureau. That compares with an increase of 5.5 percent for the nation as a whole, and 6.5 percent for its metropolitan areas — which, just to be clear on what we’re talking about, are defined as “one or more counties that contain a city of 50,000 or more inhabitants, or contain a Census Bureau-defined urbanized area and have a total population of at least 100,000 (75,000 in New England).”

Thirty-nine of these fast-growing metros are in the South and 19 in the West. This should come as no big surprise, given that these two regions are estimated to have accounted for 86 percent of the country’s almost-17-million-person increase in population since 2010. None of the fast-growth areas is in the Northeast, but there are five in the slowest-growing of the four regions delineated by the Census Bureau: the Midwest.

One of these Midwestern standouts, Iowa City, Iowa, is home to a large research university, a frequent catalyst for local economic success. Another, Des Moines, Iowa, is a state capital with a metro-area population of 645,911, which is in keeping with urbanist Aaron Renn’s dictum that “If you want to be a successful Midwestern city, it helps to be a state capital with a metro area population of over 500,000.” Two, Bismarck and Fargo, North Dakota, have been beneficiaries of a big shale-oil boom in their state.

That leaves Sioux Falls, South Dakota, which has seen its metro-area population rise 13.5 percent since 2010 (and 68.8 percent since 1990), to 259,094. There’s no major university in town; local legend has it that city fathers were given the choice 150-plus years ago between the University of South Dakota and the South Dakota State Penitentiary, and they opted for the latter because they figured it would bring more jobs. The state capital, Pierre, is more than a three hours’ drive away. The signature local industry used to be meatpacking — and there’s still a big, exceptionally fragrant Smithfield Foods Inc. pork-processing plant along the Big Sioux River about a mile north of downtown.

This does not sound like a recipe for economic success in the early-21st-century U.S.! Yet Sioux Falls is undeniably booming. What’s up with that?

I am not the first to attempt to answer this question: James and Deborah Fallows devote the first chapter of their new book “Our Towns: A 100,000-Mile Journey into the Heart of America” to it, and if you want a detailed account complete with Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade balloons (manufactured in Sioux Falls by Raven Industries Inc.), that’s where you really need to go. Last year, meanwhile, the Wall Street Journal described how “As Many Midwest Cities Slump, Sioux Falls Soars,” while the New York Times, early to the topic and focused on what really matters, published “A Food Scene Grows in Sioux Falls, S.D.” in 2014.

Still, this is a subject worth repeated examination, given that lots of city leaders around the country must wonder how they can capture some of that Sioux Falls magic. And I have two possibly useful observations, one that occurred to me while visiting Sioux Falls recently and another that jumped out as I looked through the metro-area population data just now.

Let’s start with the latter: Remember how I said that none of the fastest-growing metros is in the Northeast and five are in the Midwest, even though the Midwest’s population is growing more slowly (1.9 percent since 2010) than the Northeast’s (2.1 percent)? Go further down the rankings of metropolitan-area growth, and this discrepancy stands out even more. There is not a single metropolitan area in the Northeast that has grown at or faster than the national metro-area rate of 6.5 percent since 2010, and only two (Boston and State College, Pennsylvania) have grown at or faster than the overall national rate of 5.5 percent. Yet there are 19 metro areas in the slower-growing Midwest that make the first cut, and 23 that make the second.

What the Midwest has been experiencing is a great reshuffling. On its eastern side, as I wrote about Ohio last month, older industrial cities and to a lesser extent rural areas have been shedding people and jobs. To the west, the story is almost entirely one of rural areas depopulating as, among other things, bigger, better agricultural equipment allows farmers to plant and harvest more acres with less labor. Some of these people have left the region entirely — the Midwest as a whole has been experiencing net domestic out-migration for decades — but many are flocking to the region’s growth hubs, a mix of college towns, state capitals and a few other cities. So the headline on that Wall Street Journal article, while not factually wrong, is misleading. Lots of Midwestern metro areas are soaring, or at least growing faster than the national average, even as the region as a whole plods along.

Still, it cannot be denied that the Dakotas trio of Fargo, Bismarck and Sioux Falls has soared the highest since 2010. While I dismissed the former pair earlier as beneficiaries of North Dakota’s oil boom, in Fargo’s case that’s not really fair, given that it is all the way at the other end of the state from the oil wells (Bismarck, the state capital, is much closer); plus, it was growing at a healthy clip before all the fracking started. Its success raises many of the same questions that Sioux Falls’s does, and they probably have some quite similar answers. But it is Sioux Falls that I happened to visit recently, and the Sioux Falls metro area’s growth has outpaced Fargo’s if you measure from 2000 or 1990.

What did Sioux Falls do to encourage such rapid growth? Most famously, it persuaded Citibank to move its entire credit-card operation to town in the early 1980s after the South Dakota Legislature voted to repeal the state’s usury laws, which limited the interest rates banks could charge. Other card issuers followed, attracted not only by the ability to charge as much interest as they pleased but also by very low taxes. South Dakota has no corporate or personal income tax, and when the Tax Foundation last measured overall state and local tax burdens in 2012, South Dakota’s ranked second-lowest, just behind oil-rich Alaska.

This isn’t just the story, though, of a state luring industry with low taxes and deregulation. South Dakota’s workforce happens to be pretty solid, too. College graduates make up a smaller share of the adult population there than nationwide, but the state ranks near the top in the percentage of adults with high school diplomas and associate degrees, as well as in literacy rate, and it has among the highest labor-force participation rates and lowest unemployment rates.

Also, the financial sector ceased being the big economic growth story in Sioux Falls a while ago. The area still has the nation’s third-highest location quotient for financial employment, a measure of how concentrated the industry is in the area relative to the nation as a whole, trailing only the metropolitan areas of Bloomington, Illinois (home of State Farm), and Des Moines (another big insurance center). But metro Sioux Falls has fewer financial-sector jobs now than it did in 2008, even as other payroll employment has risen 20 percent.

It can’t have hurt that, before it started shedding jobs, the credit-card industry provided Sioux Falls with a billionaire sugar daddy. Minnesotan T. Denny Sanford had founded and sold a company representing manufacturers of construction materials and was trying and failing to enjoy retirement when, according to Forbes, he bought a 10-branch South Dakota bank in 1986 from a friend who needed to unload it because he was going through a divorce. A few years later, Sanford hired a young executive from Citibank’s Sioux Falls operation to see if there was a credit-card niche that his First Premier Bank could exploit. What they settled on was high-interest-rate cards for people with terrible credit. First Premier is now a major national card issuer, and while its practices sometimes garner bad media coverage, they also bring in tons of money — money that Sanford, now 82, has pledged to give away fast enough that he can die broke.

Sanford has reportedly donated nearly $1 billion to one of the two Sioux Falls-area hospital systems, which is now called Sanford Health and bills itself as “the largest rural, not-for-profit health care system in the nation.” One of its affiliates, Sanford Research, employs 200 medical researchers in Sioux Falls. Regional centralization of health care has made it a key source of jobs in lots of mid-sized cities, but Sanford’s gifts have helped make those jobs even more plentiful and well-remunerated in Sioux Falls than is the norm. Sanford has also helped fund the Sanford Underground Research Facility, a state-managed physics lab in a former gold mine in the Black Hills at the western edge of the state; the new Madison Cyber Labs at Dakota State University about an hour’s drive northwest of Sioux Falls;and the Sanford School of Medicine at the University of South Dakota about an hour’s drive to the south.

No one else in Sioux Falls has amassed anything like Sanford’s fortune, but other businesspeople in the city feel similarly compelled to chip in. The new mayor, Paul Ten Haken, is the founder and former chief executive of a Sioux Falls-based marketing technology company who decided it was time to “pivot” to public service, while his predecessor had been a Citibank and First Premier executive before taking charge at City Hall. Since 1987, an initiative called Forward Sioux Falls has been relying on donations from local businesses to finance most of the area’s economic development efforts, which at the moment include a giant new industrial park at the north end of town and a nearby “corporate and academic research park” affiliated with the University of South Dakota. “The business community recognizes that we’re in a low-tax state,” Dave Rozenboom, president of First Premier Bank (overseeing the local community bank, not the national credit-card operation) and co-chairman of the current Forward Sioux Falls fundraising campaign, told me. “So in essence we’re taxing ourselves. And we get to choose what to spend it on.”

This mixing of private and public interest may make you cringe, but as the Fallowses recount in their book, such public-private partnerships can be found again and again in successful cities and regions. And while cutting state taxes to spur growth doesn’t always work, combining low taxes with high investment seems like a pretty potent recipe for economic success, if you can find a way to sustain it.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Brooke Sample at bsample1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.