South America’s Glaciers May Have a Bigger Problem Than Climate Change

Abundant glaciers that are the source of the precious commodity called fresh water reserves are melting fast.

(Bloomberg) -- Government geologist Gino Casassa steps down from the helicopter and looks around in dismay.

Casassa is standing at the foot of a glacier, 4,200 meters (13,800 feet) above sea level. The sky over the Andes is a deep blue, but something is not right: It’s July—mid-winter in South America—and yet it’s mild for the time of year, above 0 degrees Centigrade. He takes off his orange ski jacket and walks on the bare rock.

“This should all be covered by snow this time of year,” he says, pointing to Olivares Alfa, one of the largest glaciers in central Chile, just a few meters away. “There used to be one single glacier system covering this whole valley; now it’s pulled back so much that it’s divided into four or five smaller glaciers.”

Chile has one of the world’s largest reserves of fresh water outside the north and south poles, but the abundant glaciers that are the source of that precious commodity are melting fast. That’s not just an ecological disaster in the making, it’s rapidly becoming an economic and political dilemma for the government of Latin America’s richest nation.

A toxic cocktail of rising temperatures, the driest nine-year period on record and human activity, including mining, is proving lethal for the ice of Chile’s central region. Built up over thousands of years, the ice mass is now retreating one meter per year on average.

Less than two decades from now, some glaciers will have disappeared, while the total volume of all glaciers in Chile will have shrunk by half by the end of the century, says Casassa. That’s an acute problem since Chile, which has 80% of South America’s glaciers, is also the Americas country most at risk of extremely high water stress, according to the World Resources Institute. More than 7 million people living in and around the capital, Santiago, rely on the glaciers to feed most of their water supply in times of drought.

Chile’s government is well aware of the issue. A glacier unit was established in 2008 and tasked with producing an inventory of glaciers with the aim of protecting them and raising awareness of their importance. But its resources are limited: it had a staff of just seven last year—Casassa is the unit’s director—and has so far published a single register of glaciers, in 2014, using decade-old data. The unit is due to issue a second inventory later this year allowing the first ever comparison of all Chile’s glaciers.

Not everyone is content to wait. An opposition bill now before parliament aims to lock in legal protection for glaciers. But President Sebastian Pinera’s center-right government has come out against it, arguing that if implemented, the measures would harm Chile’s economic development, and specifically its lucrative mining industry.

Glaciers happen to cover some of the massive copper deposits that make Chile the world’s largest producer of the metal, with about a third of the world’s copper output coming from its mines each year. Mining is key to Chile’s economy, making up 10% of its gross domestic product and comprising just over half its exports.

That economic reality is at the heart of the government’s quandary, evaluating the trade-offs required to protect the environment while supporting an industry worth some $19 billion to the economy. Chile’s minister for mining, Baldo Prokurica, insists the twin aims are not mutually exclusive.

“Mining can be done without damaging the environment and that’s what we want to do,” Prokurica said in an interview in Santiago, pointing out that countries with similar challenges such as Canada, Norway and the U.S. have higher environmental standards and still manage to mine without a glacier law.

The bill proposes all glaciers and their surroundings become protected areas, bans non-scientific interventions and considers any violations of the rules to be crimes. That’s too broad brush for Chile’s government, which plans its own environmental legislation. “I believe in preserving the glaciers, but also in mining,” said Prokurica.

Pinera’s minority government is still on the back foot over the bill in the same year that it’s due to host the United Nations COP25 climate change summit, making it an easy target for charges of hypocrisy by opponents.

“If they don’t support the glacier bill, it will show their bid for COP was playing to the gallery,” says Guido Girardi, the opposition senator who sponsored the legislation. “We’re facing a catastrophe and not protecting glaciers is not an option anymore.”

Glaciers have long been the bane of the mining industry. During the 1970s, state-owned copper miner Codelco removed glaciers covering a rich deposit in the mountains northwest of the capital to allow development of its Andina mine. At a time when Chile had almost no environmental protections, the act was celebrated as a great feat of engineering.

Scientific advances mean that it’s now known glaciers help lower temperatures and increase air humidity for a 50-kilometer (30-mile) radius. They’re also the reason that rivers in central Chile carry about the same volume of water during the current extreme drought as in normal conditions. In a dry year, as much as two-thirds of the water in river systems feeding Santiago comes from the glaciers high up in the Andes.

The upshot is that as drought conditions become more prevalent from Cape Town to Chennai in India, Chile remains relatively sheltered. Some 70% of the country’s population of 18 million lives in areas where glaciers make the difference.

But that natural safety net is coming under increasing strain. While most mines in Chile are in the country’s northern Atacama desert, miners are moving south in search of newer and richer deposits—and encountering glaciers on the way.

“Requests to explore and mine in areas with a large presence of glaciers are only increasing,” said Francisco Ferrando, a glaciologist and professor at Universidad de Chile in Santiago.

Most of Chile’s glaciers are in the southern Patagonia region, and while a few are located inside national parks and hence protected, the majority aren’t, meaning that any intervention is treated on a case-by-case basis. White glaciers, where the ice is in direct contact with air, enjoy wider protection than less well-known rock glaciers—masses of frozen water that have sat beneath layers of rock for millennia.

An academic paper from 2010 found that a third of all rock glaciers in central Chile had been directly impacted by mining activities such as road building, drilling platforms and depositing waste on top of the ice. In addition, dust from trucks and explosions in pits as well as vibrations from heavy machinery accelerate the melting. Mining itself is water intensive since it’s needed in each step to produce copper, with usage forecast to rise.

Almost every large mining company operating in Chile has impacted glaciers, including Anglo American Plc. at its Los Bronces mine and Antofagasta Plc. at Los Pelambres, according to the paper.

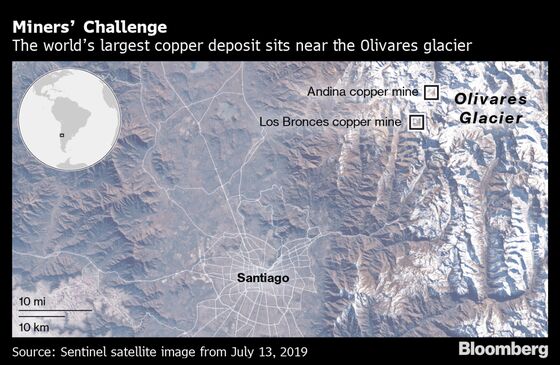

Anglo American’s Los Bronces operation and Codelco’s Andina mine are exploiting the world’s largest copper deposit in the Andes, about 40 miles from Santiago. Only a rock ridge separates them from the Olivares Alfa glacier. The two giant pits, the mining trucks and dust from the explosions are clearly visible from a helicopter.

With both companies planning new billion-dollar projects to maintain production at current levels, alarm bells have been set off among environmentalists, who say that mining is hastening the process of desertification.

It’s a charge miners reject. Joaquin Villarino, the president of industry group, Mining Council, has said that glaciers are shrinking because of climate change, and that pollution from transport and other industrial activities in Santiago are also having an impact. The glacier bill contains “serious errors,” he said.

All the same, miners are taking action. While Codelco is doing early engineering work on an expansion of its open-cast Andina mine, its sister mine, Los Bronces, will go partly underground in a $3 billion plan to avoid impact on the surface.

Owner Anglo American “acknowledges the importance of glaciers and has the conviction that mining activity and the preservation of the environment can coexist,” the company said in an emailed response to questions. Codelco declined to comment on its plans for Andina.

Pinera’s administration is going on the offensive. Approval of the glacier bill would force four mines including Andina and Los Bronces to halt operations, costing billions of dollars and more than 34,500 jobs, according to a report by the government’s copper commission Cochilco. Copper output would fall by 11% through 2030, impacting global metals markets, it said.

Casassa, the geologist, sees the impact of climate change accelerating but shares the government’s assessment that there is no need for specific glacier legislation.

The government may be powerless to stop the bill, however, since it lacks a majority in either chamber of parliament. Lawmaker Girardi says it could clear both the senate and chamber of deputies by early next year, an outcome he sees as of global significance.

“All the changes we are seeing, all the climate catastrophes across the world are just the beginning,” Girardi said. “Chile’s glaciers are strategic, not just for our country, but for all humanity.”

--With assistance from Maria Jose Campano and Samuel Dodge.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Alan Crawford at acrawford6@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.