Roche Turns to App in Fight Against Multiple Sclerosis

Sneaking Into Patients’ Pockets, One Medical App at a Time

(Bloomberg) -- Most afternoons, Stephanie Buxhoeveden takes a few moments to march back and forth, making at least five U-turns, stand at attention and pinch a digital tomato on her phone.

The unusual ritual is intended to help Buxhoeveden track an unpredictable neurological disorder that largely strikes young women: multiple sclerosis. She’s playing games in an app called Floodlight, which logs her activity and sends it to the servers of drugs giant Roche Holding AG.

“One of the frustrations of having MS is that it’s different from day to day,” said Buxhoeveden, 31, who is a paid consultant for Roche. Even if a doctor’s appointment falls on the one good day in a series of tough ones -- which inevitably happens -- with the app “you can track your symptoms over time,” she said.

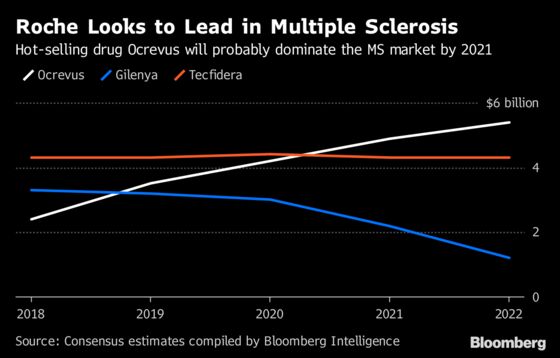

The Swiss drugmaker has had success in the multiple sclerosis market with a new medicine called Ocrevus, which is on track to exceed $2 billion in sales this year and will probably lead the $23 billion global market for branded MS therapies by 2021, according to Bloomberg Intelligence. At the same time, Roche is trying to get 10,000 patients to start using Floodlight in an ambitious attempt to better understand the debilitating disease -- but also to get patients to give companies a front seat to intimate details of their day-to-day lives.

There’s much to gain from being in a patient’s pocket every day. Pharmaceutical companies get direct access to their clients, and to a trove of data that they can hope to ultimately monetize. Rivals from Pfizer Inc. to Novartis AG are thinking along the same lines, with a range of apps for everything from quitting smoking to eye disease. Multiple sclerosis lends itself to this kind of exercise better than some because a smartphone’s sensors can objectively observe how patients move, which is one of the best ways to track the disease’s development.

Doctors usually only see MS patients twice a year, making it difficult to pin down small changes as they occur, said Jennifer Graves, director of neuro-immunology research at the University of California, San Diego, who helped lead the pilot study for Roche’s app.

“For years, I’ve had some patients, particularly those who come from engineering fields, come to the office with Excel spreadsheets where they’ve tried to do this type of self-monitoring,” Graves said.

Floodlight intends to keep participants anonymous, identifying each user only by a unique number. Participants don’t need to be on Ocrevus or even disclose what medicine they’re taking. Once they start using the free app, they can share their results with their doctors, possibly improving their own care.

The resulting data are available to anyone on Floodlight’s website. The point is to help scientists and physicians around the world “complete a more holistic picture with the hope to one day help improve care," the website says. The app can track users’ movements throughout the day, even when it’s not in use, something Roche describes as “passive monitoring.”

The project’s methods for keeping people anonymous raise some concerns about privacy. The company says it’s taking “every precaution” to ensure that Floodlight data stays anonymous.

Drugmakers are drawn to technology that gives them a rare opportunity to interact directly with patients. Roche’s chief executive officer points to data as the single biggest catalyst for change in the pharma industry in coming years.

“It’s an experiment,” CEO Severin Schwan said in a Sept. 13 interview. “The idea is to get access to real-world data, which then again results in better R&D. If this works well, we could try this in different diseases.”

Digital tools can help “identify patterns in what seems like chaos,” said Katherine Heller, an assistant professor of statistical science at Duke University, which started a similar open-to-all-comers multiple sclerosis app study last year. “That wasn’t possible until fairly recently. Smartphones give us this amazing capability with minimal intrusion into people’s lives.”

MS destroys the insulation that protects the nerves in the brain and spinal cord, disrupting signals. There is no cure, and patients, on average, have a slightly shorter life expectancy.

The games that Buxhoeveden plays on Floodlight mirror the tests that, as a nurse practitioner who also treats people with multiple sclerosis, she gives patients when they visit her clinic. Originally in training to be a nurse for anesthesiology, she switched her specialty after being diagnosed almost seven years ago.

“I foresee replacing the testing I do in the office with actually going onto my patient’s profile and looking at their Floodlight data,” said Buxhoeveden. “You log on, you play a couple games, and then you move on with your day.”

Roche started out with a pilot trial to show that results from Floodlight’s games match up to standard measures for following the progression of multiple sclerosis, such as asking patients to do a timed 25-foot walk or put pegs into holes on a board.

After the pilot study showed a correlation, the drugmaker started working to recruit for a bigger trial this year. The research will run for five years and is open to people without MS, who will function as a control group of sorts. Roche wouldn’t say how much it’s spending on the project.

There are some challenges: Roche needs to convince people to download the app and engage with it. In the five months since the open Floodlight trial started in the U.S., only 400 users have signed up. The company plans to boost recruitment efforts this fall and make the app available in Europe by the end of the year.

And then there’s the privacy issue. While users remain anonymous, Roche provides partial information such as country of residence, year of birth, height and weight that may be enough for a third party to figure out who the participants are in the confined world of people with multiple sclerosis, according to David Choffnes, a computer and information science professor at Northeastern University in Boston. That could ultimately impact insurance rates, a job application or something else that’s hard to foresee at this time, he said.

“We have to think of risks that are not only out there today, but that might happen in the future,” Choffnes said. "That’s why, as a privacy researcher, I see this and get very concerned.”

In the long term, Floodlight and its ilk could be used to draw a detailed picture of how much a treatment is helping a patient, giving drugmakers a better negotiating position with payers, said Peter Pitts, a former FDA associate commissioner and president of the Center for Medicine in the Public Interest. “It’s a pocketbook issue,” Pitts said.

Novartis this year gave up on an effort to use video-based machine learning analysis to help doctors see how patients’ disease was progressing -- a tool that unlike Roche’s Floodlight was mostly aimed at doctors.

Roche rival Biogen Inc. designed a digital journal for patients. Its app Cleo -- called Aby in the U.S. -- has already been downloaded more than 72,000 times in the five months since its launch, said Thibaud Guymard, who heads product and strategy at Biogen’s digital-focused Healthcare Solutions group.

After three months of using Roche’s app, Buxhoeveden said Floodlight had proven one of her suspicions to be true: her MS symptoms act up more on hot and humid days. Seeing the objective evidence in a graph forced the Virginia resident to change her ways, she said. “I do now take a little bit of extra time and effort to combat the heat fatigue, that’s for sure.”

--With assistance from James Paton.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Benedikt Kammel at bkammel@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.