Fannie and Freddie Changes Could Lower Housing Costs for Millions of Americans

The U.S. is making the biggest change in a generation to the roughly $4.4 trillion market in mortgage-backed securities.

(Bloomberg) -- Starting Monday, the U.S. government is making what’s widely described as the biggest change in a generation to the inner workings of the roughly $4.4 trillion market in mortgage-backed securities issued by the country’s two housing market giants, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. This change could mean lower housing costs for millions of Americans – or higher ones, depending on whom you ask.

1. What do Fannie and Freddie do?

They package lenders’ mortgages into bonds known as mortgage-backed securities and guarantee the underlying loans. The bonds essentially shunt monthly principal and interest payments from a multitude of homeowners over to investors. The process lets lenders free up their balance sheets to issue new mortgages, while offering the market large quantities of what for years were seen as extremely safe investments. The system melted down in the 2007-2008 financial crisis, forcing the government to take direct control over the pair. Fannie and Freddie quickly rebounded, and their so-called agency MBS fuel the deepest and most liquid U.S. debt market after Treasuries.

2. What’s changing?

Fannie and Freddie’s MBS are becoming more standardized at the behest of the Federal Housing Finance Agency, the regulator that was created in 2008 to oversee Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. It’s the overseer of the two agencies, which are known as government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) because they were created by Congress. One of the changes the FHFA is enacting is making Freddie Mac give homeowners’ mortgage payments to investors in 55 days, instead of its current 45 days, to mimic Fannie Mae’s timeline. From now on, both GSEs mortgage pools will be wrapped into what will be known as UMBS – uniform mortgage-backed securities.

3. Why would that be a good thing?

Liquidity. Putting both kinds of MBS into a single pot (along with any older MBS that are exchanged into UMBS) should increase the amount traded per day. That can cut their yields, because investors will accept lower returns on a bond that they know they can more easily offload. Lower MBS yields should translate into lower interest rates for home buyers.

4. Is there a problem with that now?

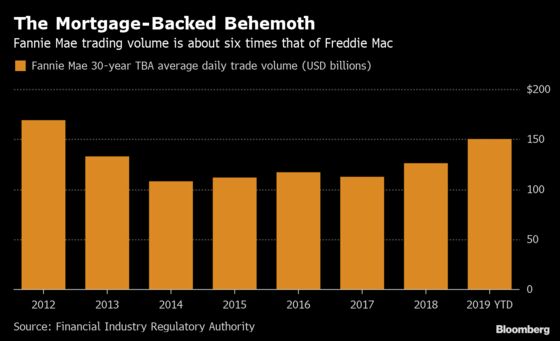

Not for Fannie Mae, whose agency MBS are already tremendously liquid. New mortgage bonds are first sold in what is referred to as the "to-be-announced" (TBA) market. That’s the most liquid part of the MBS universe, in which issuers can bundle any mortgage loans that meet established criteria into bonds. Daily trading for Fannie Mae 30-year TBA averaged about $150 billion this spring, which is second only to the volume of trading in Treasuries, and dwarfs that of corporate bonds, municipal debt or other asset-backed securities. But there is an imbalance in trading volumes between Fannie and Freddie.

5. What’s the difference between them?

Since mid-2011, Fannie Mae has accounted for well over 80% of the trading volume in 15- and 30-year mortgage pools, according to data compiled by Oppenheimer & Co. The relative lack of liquidity in Freddie Mac bonds has meant that they have traditionally traded at a discount to comparable Fannie Mae securities, and Freddie Mac has long paid a subsidy to mortgage originators to push for market share. That could come to an end as both Fannie and Freddie MBS will now trade at one price in the UMBS.

6. So what’s the biggest change?

Historically, two of the biggest differences between Fannie and Freddie’s products are the 55 versus 45 day delays on payments to investors, which are being standardized, and what’s known as prepayment speeds. Most home buyers pay off a mortgage years before it matures, either because they’ve refinanced, they move, or they pay down their loan early. The rate at which loans within an MBS are likely to be prepaid is one of the main variables mortgage traders must forecast to properly value their investment. Two securities with broadly similar characteristics, such as the same coupon, average credit score and maturity, may be valued at vastly different prices if the prepayment speeds on the underlying mortgages turn out to be dissimilar.

7. Why is that an issue?

Traditionally, there’s been a gap between the Conditional Prepayment Rate -- a number which gives the annualized percentage of the mortgage pool that’s expected to prepay-- between the two agencies’ bonds. The Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac pools of mortgages underlying UMBS must prepay at similar speeds, or else traders might be reluctant to treat the two GSEs’ bundles of mortgages as interchangeable. The FHFA has been pushing the two in recent years to keep their speeds in line with each other -- and it seems to be working. Freddie Mac 30-year 4.5% MBS prepayment speeds have averaged 1.6 CPR less than their Fannie Mae counterparts over the past half decade. Over the past year? 0.4 CPR. That is well within the 2 CPR band the FHFA says it will consider acceptable for UMBS.

8. What could go wrong?

Most analysts think the change will likely work as planned, but there are concerns, primarily about prepayment speeds. Should they diverge between the Fannie and Freddie pools that are wrapped into the UMBS, investors may start to favor one GSE’s mortgages over the other and begin trading them separately again, resulting in a three-way split of the market among Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and uniform securities -- reducing overall liquidity in the process. In order to nip such a problem in the bud, the FHFA can require the GSEs to adjust or terminate policies that are thought to be causing prepayment speeds to stray, and impose monetary fines for non-compliance.

9. What are the other worries?

Some observers foresee a potential “race to the bottom” in asset quality. That would occur if the GSEs begin to package loans exhibiting the most undesirable prepayment characteristics into the new securities, because a UMBS has just one price, and investors wouldn’t be able to account for speed differentials between the two GSEs. That would likely lead to lower prices for UMBS reflecting the deterioration in asset quality, meaning higher interest rates for borrowers.

10. What do proponents say?

They think the FHFA has the tools it needs to keep prepayment speeds aligned. That means the reform should result in a larger, more liquid and safer mortgage-backed securities market. In addition, the change to UMBS should, in the words of the FHFA, “reduce or eliminate the cost to Freddie Mac and taxpayers that has resulted from the historical difference in the liquidity” between the two. Taken together, these should reduce homeowners’ interest costs for mortgages.

The Reference Shelf

- Bloomberg Help on Issuance of Uniform MBS

- FHFA Single Security Initiative and Common Securitization Platform

- Fannie Mae Single Security Initiative and Common Securitization Platform

- Freddie Mac Single Security Initiative and Common Securitization Platform

--With assistance from Jackie Jozefek.

To contact the reporters on this story: Allan Lopez in New York at alopez11@bloomberg.net;Christopher Maloney in New York at cmaloney16@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Nikolaj Gammeltoft at ngammeltoft@bloomberg.net, John O'Neil, Dan Wilchins

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.