(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It’s a status thing. Rising Asian superpowers must have their stock connects. China has a pipe going with Hong Kong, so India also has to have one – with Singapore.

But while the People’s Republic has allowed two-way capital flows between Shanghai and Shenzhen on one side and the special administrative region on the other, New Delhi wants one-way traffic. Money will travel only into India under a stock-trading link to be established by Singapore Exchange Ltd. with the so-called GIFT City, a new international financial center in Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s home state of Gujarat.

The pipe is a peace offering from SGX to end an 18-month-long skirmish with the National Stock Exchange of India Ltd., one of its most important partners. However, the Tuesday evening announcement from the two exchanges creates new uncertainties for investors.

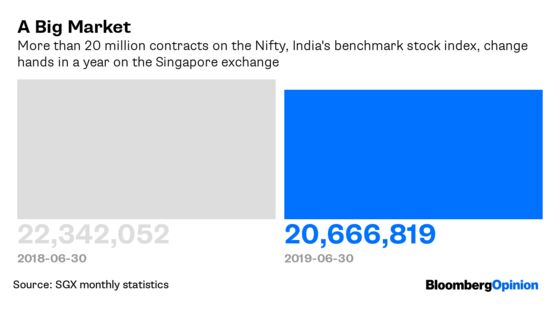

The biggest is what happens to SGX futures now that the exchange has decided to channel liquidity into a dollar-denominated contract on India’s Nifty stock-market benchmark traded in GIFT City. That’s a $450 billion question, based on the current index value and the more than 20 million futures that changed hands in the 12 months through June. It’s very likely that the Singapore contract, operated under a license granted by the NSE, will cease to exist once the pipe starts gurgling before the end of 2020.

Winding up an overseas market that’s existed for 19 years is the latest manifestation of New Delhi’s zeal to bring all trading in Indian risk back home, a nationalist project that has often backfired in the past. But if the Singapore contract stays alive, why would any foreign investor want to go to a joyless ghost town?

Forget Gujarat’s prohibition on alcohol. So far, there isn’t even a dedicated regulator in place for the international financial center, which will operate in a very different legal environment from the domestic rupee-denominated market. A recent dispute in which an Indian broker allegedly stole a client's securities and pledged them as collateral for its own trade has been so badly handled that global banks are worried if the new market will function any better. And while New Delhi announced a slew of liberal fiscal incentives last month to lure brokers and funds to set up in GIFT City, investors can’t be certain that tax laws won’t suddenly become less favorable in future. That happens a lot in India.

The dread of the Indian taxman is a showstopper. Most overseas hedge-fund managers in Singapore want to go nowhere near the local Indian market, especially if they can’t prove to Indian authorities that their fund isn’t a tax dodge. They’re happy to be left alone with uninterrupted access to the SGX Nifty in a city-state that imposes no capital gains tax.

As for specific Indian shares, the present arrangement works just fine: The investor enters into a swap contract with a global bank referencing an Indian single-stock future listed on the SGX. Unlike the SGX Nifty, single-stock Indian futures in Singapore have no liquidity. But none is needed. The bank selling the swap will use its foreign institutional investor account in India to manage its risk in the more liquid market in Mumbai. The downside from the Indian perspective is that regulators don’t know who’s actually behind the trades.

None of the big global banks like to talk about this trade because of India’s penchant to dismantle well-functioning markets wherever it can find them. Two years ago, the regulator’s decision to disallow offshore trades using onshore Indian stock derivatives created the need for Singapore-listed alternatives. When the SGX announced those products, the Indian side wasn’t amused. The spat got ugly as NSE sued SGX. The case went into arbitration.

SGX investors are happy that the stock connect will break the legal deadlock. But the whole conflict offers a sharp contrast with China. SGX started the first internationally available, dollar-denominated futures on mainland stocks in 2006, on the FTSE China A50 Index. China has never felt threatened by that contract. Beijing has instead used the time to deepen local markets, broaden foreign access, and seek higher weightings in global indexes.

If India had given the same pragmatic care to its local-currency stock market in Mumbai, there would have been no need to force foreign investors to a dollar-denominated exchange in Modi’s boondocks.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Matthew Brooker at mbrooker1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Andy Mukherjee is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies and financial services. He previously was a columnist for Reuters Breakingviews. He has also worked for the Straits Times, ET NOW and Bloomberg News.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.