Why It’s So Hard to Stop Amazon Deforestation, Starting With the Beef Industry

Why It’s So Hard to Stop Amazon Deforestation, Starting With the Beef Industry

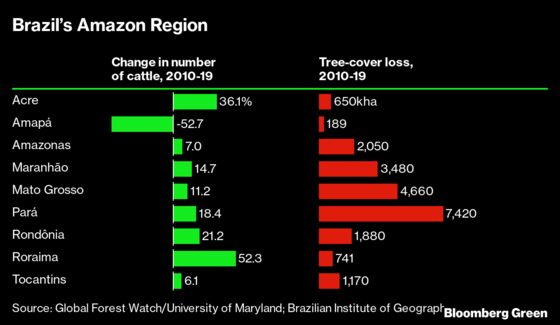

(Bloomberg) -- Brazil’s Amazon region has suffered more deforestation this year than any in the past decade. The lax environmental policies of President Jair Bolsonaro bear some of the blame; so, too, does climate change. But much can be laid at the feet of cattle farmers.

Most cows in Brazil, the world’s largest beef exporter, are grass-fed. Ranchers in the precious biome use bulldozers, machetes, and fire to make room for pastureland—a practice that’s illegal but so widespread that it’s almost impossible for strapped regulatory teams to root out. A study published in Science in July showed at least 17% of beef shipments to the European Union from the Amazon region and Cerrado, Brazil’s savanna, may be linked to illegal forest destruction.

The sheer size of the country’s beef industry—2.5 million ranchers, 2,500 slaughterhouses, and about 215 million heads of cattle spread across 3.3 million square miles (8.5 million square kilometers)—is one reason the big meatpackers say they’ve struggled to keep tabs on their suppliers. Another hurdle: Brazil’s government, which requires ranchers to file documents detailing the movements of their cattle, keeps that paperwork largely to itself.

JBS SA, the global beef industry leader, vowed in September to start monitoring its indirect suppliers—i.e., the farmers who raise the cattle to sell to the folks who sell it to JBS. That followed a similar announcement months earlier from rival Marfrig Global Foods SA. Both set the same five-year deadline to bring transparency to their supply chains. But they’ve made such promises before to little effect. This time around they’re pitching a blockchain-based system that some worry will be as easy to manipulate as the current system.

Here’s a rundown of where information gets lost.

1. The ranchers

Brazil’s cattle ranches come in all shapes and sizes, from mom and pop farms that ship out calves as soon as they’re born to one-stop shops that breed, fatten, and finish cows all on their own.

Cattle tagging (think of the microchip a veterinarian might slip under your dog’s skin) is already an established practice in large parts of the global food supply chain. For big farms it would be cheap to implement, costing about 0.5% of an animal’s revenue, according to a report from the Brazilian Coalition on Climate, Forests & Agriculture.

Uruguay, a direct competitor to Brazil, was an early adopter in the Americas, making it possible to trace a single cow from birth to plate, says Erasmus zu Ermgassen, a sustainable livestock and supply chain researcher at the Catholic University of Louvain in Belgium. “It’s not rocket science,” he says.

2. The pastures and Feedlots

Some cows spend their entire life on one ranch, but that’s pretty rare, says Holly Gibbs, an associate professor of geography and environmental studies at the University of Wisconsin. Cattle move two or three times on average, according to her research, and sometimes as many as six times before they’re slaughtered. That constant shuffling makes it all too easy to hide a cow’s real origin, a practice known as “cattle laundering.”

Each time a cow is moved from one property to another, the state issues a guide to animal transport, or GTA, which identifies the shipping farm, the receiving farm, the number of cattle being moved, and the date of transfer. This process helps ensure the safety of the overall herd in the case of a disease outbreak, but deforestation fighters have also latched on to the documents as a potential key to traceability.

Currently the only people who regularly get to see the GTAs are the ranchers, the drivers moving the cattle, and food sanitation officials. The government says making them more widely available would violate ranchers’ privacy rights, even as the secrecy helps bad actors evade the law.

3. The Direct Suppliers

When JBS, Marfrig, and smaller rival Minerva SA say they’re confident they’re not contributing to the destruction of the Amazon rainforest, what they really mean—and what they acknowledge in sustainability reports—is that the suppliers they get their cattle from aren’t themselves involved in deforestation. But almost no direct suppliers actually breed and raise all the cattle they sell, Gibbs says.

In its 2019 annual report, JBS announced that DNV-GL, a Norwegian social and environmental auditor, had confirmed that 100% of the cattle it acquired from the Amazon were compliant with zero-deforestation commitments made in 2009 among companies, public prosecutors, and groups such as Greenpeace. DNV-GL, which is no longer auditing JBS’s supply chain, later clarified in a letter to forest groups that it actually found “non-conformity” because the company didn’t have systems in place to trace its indirect suppliers. “JBS cannot use the assessment report as evidence of good practices throughout their total supply chain,” Brazil Area Manager Adriano Duarte wrote in the letter. JBS says it’s never claimed the audit referred to indirect suppliers, and that 100% of its direct cattle purchases are in line with environmental commitments.

4. The Slaughterhouses

Brazil is a beef-producing powerhouse, slaughtering almost 32 million cattle per year, according to national statistics institute IBGE. JBS, Marfrig, and Minerva are the best-known names, but there are as many as 2,500 smaller butchers and meatpackers, according to Neoway, a big data and artificial intelligence company based in São Paulo.

Relying on companies to police themselves and their suppliers is unrealistic; only the government can do that, through a universal monitoring system, says Raoni Rajão, a social sciences professor at the Federal University of Minas Gerais in Brazil. “There is no other actor able to solve this issue,” he says. Gilberto Tomazoni, JBS’s chief executive officer, holds a similar opinion. “If the entire sector isn’t engaged, Brazil will continue to have all the same problems,” he says.

5. The Consumers

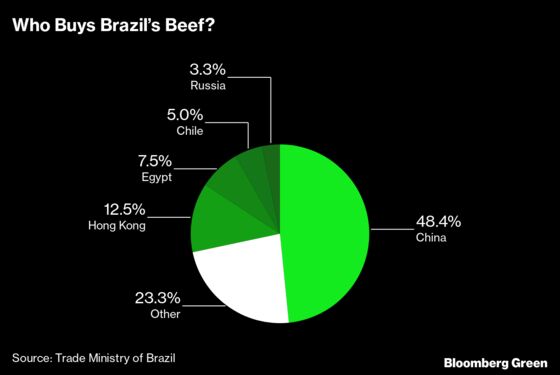

China—including the mainland and Hong Kong—is by far the biggest buyer of Brazilian beef, accounting for almost 60% of all foreign purchases from January to October, according to government data. Egypt, Chile, Russia, and Saudi Arabia round out the top five consumers. None of these has transparency requirements related to deforestation, Rajão says. Among the major importers, only the EU has talked about it.

Brazil may be the world’s biggest beef exporter, but the locals are big meat eaters, too. Four-fifths of the almost 11 million tons the country processes each year go to the domestic market, says Abiec, Brazil’s beef exporter group. Consumers inside and outside Brazil, including supermarkets and restaurants, need to show their outrage more and refuse to buy Brazil’s beef until the system is cleaned up, says Paulo Barreto, a senior researcher at Imazon, a nonprofit focused on the Amazon. “This step is missing,” he says.

Cattle cause more climate problems than deforestation. Methane—mostly released in burps—accounts for as much as 5% of total greenhouse gas emissions. If meatpackers can’t prove their steaks don’t come from cleared rainforest, their ability to account for supply chain emissions will remain a question mark.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.