Saudi Attacks Aren't Bullish for One Energy Market

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- There’s one energy market that won’t feast on renewed fear of conflict in the Middle East. The windfall accruing to oil producers after the weekend’s attacks in Saudi Arabia is a bad sign for U.S. natural gas.

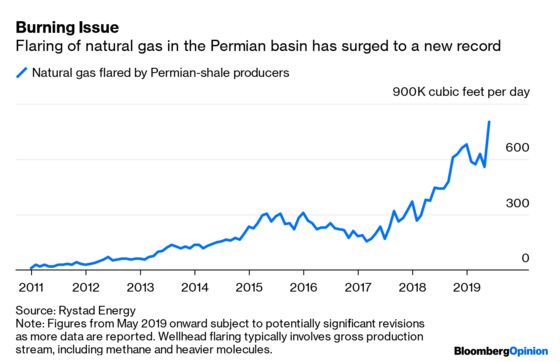

Far from scrambling for supplies, production of freedom molecules just hit a new record. Ordinarily, that would be cause for celebration. And it is for customers. Producers, meanwhile, are drowning in the stuff – or, rather, burning it off. Flaring of natural gas, when producers burn the excess that they can’t use or sell, is also hitting records. Preliminary data from Rystad Energy show producers in the Permian shale basin flared more than 800 million cubic feet per day in June. On a trailing 12-month basis, they burned off almost enough to supply the entirety of Texas residential gas demand.

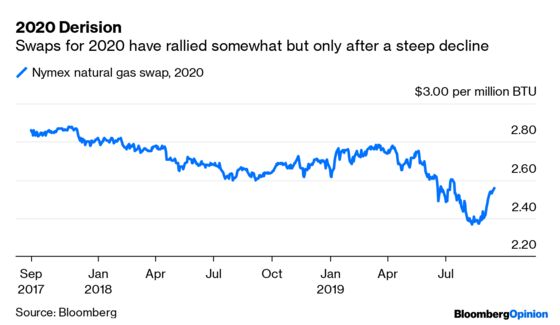

This is why even though the benchmark Nymex gas futures price has risen almost 30% over the past five weeks, it still trades below $2.70 per million BTU. Average swaps for 2020 are back merely to where they stood in mid-July.

We’re dealing with a broken market here, and the re-emergence of oil’s geopolitical premium exacerbates that.

This is because a significant portion of the growth in U.S. gas supply is effectively de-linked from the price. So much gas is being flared in the Permian basin because it’s a mere by-product of oil output. Associated gas comes out of the ground alongside oil. Producers care more about the latter, since it’s worth much more and easier to transport (oil can be trucked out if need be; not so with gas).

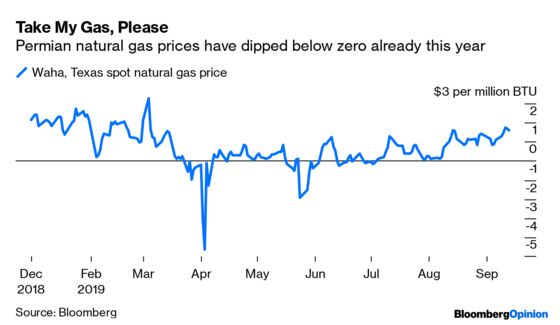

That means gas prices can fall very low and still not persuade frackers to ease off. How low? Speaking at a forum organized last week by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, Rusty Braziel of RBN Energy estimated that if oil is trading at $55 a barrel, a typical Permian well could break even with gas priced as low as negative $4. That’s right, they could pay customers to take the gas and still do OK – which happened in West Texas already this year.

As it is, after the Saudi attacks, West Texas Intermediate crude is trading back above $60. At $65, Braziel estimates the breakeven gas price would be negative $8.

The renewed geopolitical premium in oil is like a windfall for U.S. frackers, adding dollars to the price they get and displacing competing supply from the market. It’s no accident that the strongest-performing E&P stocks on Monday morning are walking wounded such as Whiting Petroleum Corp. and California Resources Corp. Chesapeake Energy Corp., a company that exemplifies the shale-gas boom and bust, is up more than 10% as I write this.

Besides adding to earnings, higher futures prices offer producers a chance to lock in revenue for next year via hedging. As of now, 2020 swaps are up by less than $3 a barrel, to just over $55, reflecting the concentration of fear in the near end of the curve. But if Saudi Arabia takes longer to fully restore output or, more ominously, we enter a cycle of retaliation and escalation, then that fear would spread further out. Anything that encourages more rather than less fracking adds to the glut weighing on gas prices.

In theory, even if pricing isn’t affecting gas production, all that flaring should ultimately cause another mechanism to kick in and limit supply. Flaring requires waivers from the Railroad Commission of Texas, which regulates the state’s oil and gas industry. And the fact that a swathe of the state is now lit up like a Christmas tree most nights suggests some sort of limit ought to be near.

Hopefully you’re sitting down when I tell you the Railroad Commission seems to be just fine with all that potentially salable fuel (and greenhouse gas) just being vented or burned off into the atmosphere. Remarkably, they ruled in a recent case in favor of a producer who wanted to flare gas even though its wells were connected to pipelines that could have taken it away. This was a function of cost, not physical necessity.

Such actions could ultimately prove harmful to the industry, and not just in terms of provoking an environmental backlash. Gabriel Collins of Rice University’s Baker Institute points out that if pipeline operators must now contend with the possibility that producers can just flare even if pipelines are there, then those operators may demand more-stringent contract terms or just think twice about building new capacity at all.

If we are entering a prolonged period of upheaval in the global oil market, however, then what is the likelihood regulators in a state exemplifying U.S. energy dominance will choose now to take a more restrictive approach? Yet, absent that, as Collins says, “ultimately, you’re putting all the optionality in the hands of the producers.” And those peculiarly Texan torches and that moribund gas market tell you exactly what producers like to do best.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Mark Gongloff at mgongloff1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.