Swedbank’s Estonian Unit Actively Sought Rich Russian Clients

Swedbank’s Estonian Unit Actively Sought Rich Russian Clients

(Bloomberg) -- The latest Nordic bank to be tainted by a Baltic money laundering scandal was actively involved in soliciting wealthy Russian clients at the height of the global financial crisis.

Swedbank AB, through its unit in Estonia, tried to recruit people to help build its international private banking unit by telling them they’d be involved in working to help “our Russian and CIS customers achieve their goals,” according to job postings at the time.

Stockholm-based Swedbank, which is the biggest lender operating in the Baltic region, last week acknowledged it handled suspicious flows after Sweden’s main broadcaster, SVT, found about 40 billion kronor ($4.3 billion) in questionable transactions linking the Swedish lender to the Danske Bank A/S money-laundering case. Swedbank has lost roughly a fifth of its market value, or about $5 billion, since allegations against it first surfaced last week, and its shares were trading down about 2 percent on Tuesday.

Swedbank responded to the SVT report by naming EY to investigate. But on Tuesday, just five days later, the bank dropped the accounting firm following revelations that EY was itself under investigation by Danish authorities over the Danske affair.

The Big Picture

The allegations add to a picture that suggests Nordic banks were the go-to firms to help people in the former Soviet Union channel billions of dollars into the West until as recently as 2015. Danske is being investigated by the U.S. Justice Department and the Securities and Exchange Commission after admitting that a large part of about $230 billion in money that flowed through its Estonian unit was probably illicit.

Swedbank has repeatedly distinguished itself from Danske, pointing to what it characterized as a business based on local clients with local operations. Spokesman Gabriel Francke Rodau declined to comment on questions about the lender’s international private banking operations.

‘A Lot of Questions’

In an emailed response, Francke Rodau said that the bank is currently “getting a lot of questions regarding our Baltic operations,” and that it wants to “provide the same facts to all external stakeholders at the same time. So I do not want to comment on specific details. But note that there is an interest regarding this detail.”

In an op-ed published in Estonia’s Postimees newspaper, the head of the country’s financial watchdog, Kilvar Kessler, said that “probably a majority of universal banks” doing business in Estonia “were offering services to non-residents in the past.”

“Some to a lesser extent or more passively, others more actively,” he said. “Suspicious activity by clients wasn’t analyzed, or there was no will to analyze, because it generated revenue, after all.”

Swedbank Held Yanukovych Linked Accounts in Estonia

‘Shoddy Controls, Dubious Business’

The media are “now publishing details shedding light on the banks non-resident business of the past, which is being judged in the light of present-day perceptions,” Kessler said. He also said the Estonian financial supervisor isn’t surprised by references “to shoddy risk controls and dubious business of the past” and “won’t be shocked if there will be further details about the past that now embarrasses the banks.”

On a Feb. 20 analyst call, Swedbank Chief Executive Officer Birgitte Bonnesen and spokesman Francke Rodau described the lender’s non-resident portfolio as negligible, also going back as far as 2007.

The International Private Banking department at Swedbank’s Estonian subsidiary started in 2006, when it still went under name of Hansabank, and continued to operate until at least 2009. At that point, the bank changed the unit’s name to Swedbank, according to archived copies of websites.

After 2015

According to a person familiar with the operations, who asked not to be identified by name given the sensitivity of the case, Swedbank’s international private banking unit was focused on non-resident customers. It was reorganized in 2009, but the non-resident business continued after that, the person said.

The same person also said that at least 75 non-resident clients of Danske Bank opened accounts at Swedbank after the Danish lender started closing its non-resident accounts in 2015.

Swedbank is now being investigated by the financial supervisory authorities of Sweden and Estonia.

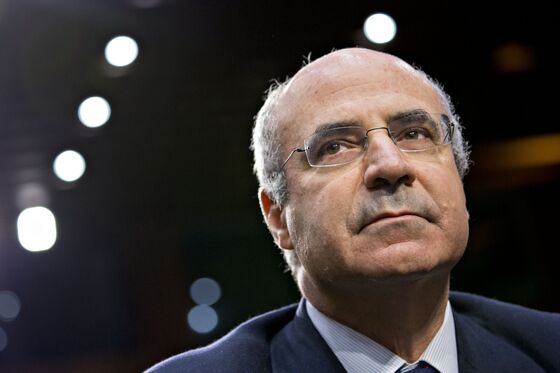

The development has raised serious questions about the extent to which the Nordic and Baltic regions became a central causeway in Europe for crooks to channel dirty money from the east. Bill Browder, an investor who’s made a career of chasing money launderers, says he has evidence suggesting that “a good part of the Nordic banking system has been used by Russian money launderers, and neither the regulators nor the banks did anything about it for many years.”

Handling money for wealthy non-resident Russian clients isn’t necessarily illegal. But Swedbank had made a point of presenting itself as a bank that focused on local residents.

Dirty money coming from Russia and the Commonwealth of Independent States threatens Europe’s financial system and risk undermining democracy in the region, according to a draft European Parliament report. It calls for the creation of a new European financial police.

--With assistance from Aaron Eglitis and Gregory L. White.

To contact the reporters on this story: Ott Ummelas in Tallinn at oummelas@bloomberg.net;Irina Reznik in Moscow at ireznik@bloomberg.net;Frances Schwartzkopff in Copenhagen at fschwartzko1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Paul Sillitoe at psillitoe@bloomberg.net, Tasneem Hanfi Brögger, Niklas Magnusson

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.