Rivian’s Long, Messy Road to Its First Electric Truck

How R.J. Scaringe kicked his gas habit, wandered into desert and came back with what might be the next great, American car company

(Bloomberg) -- (This is the first story in a series examining Rivian’s origins and its future. Read the next installment here.)

Seth Moczydlowski approached a squat industrial building a few miles south of Florida’s Kennedy Space Center. It was Oct. 3, 2011, and he was reporting for his new job at the company that would become electric-car maker Rivian. His boss, R.J. Scaringe, emerged, limping badly.

Scaringe had a crush on a woman doing a half-marathon. He had run it with her.

“Did you train for it?” Moczydlowski asked.

“Not really.”

Cold-starting a 13-mile race with a romantic interest takes confidence, perseverance and a healthy dose of naivete. The same chemistry helps start a car company.

When he ran his race, Scaringe was about four years into building the company that would become Rivian. The Irvine, California-based startup, which an initial public offering around Thanksgiving may value as high as $80 billion, has a multibillion-dollar contract with Amazon.com Inc. to build delivery vans and this month has started delivering its first production vehicle, a $67,500 luxury pod, to customers. Dubbed R1T, the machine is aimed at rocky trailheads and Whole Foods parking lots, and resembles a traditional pickup worked over by a scrum of Apple designers.

Billion-dollar startups tend to share a triumphalist origin story: a neurotically focused founder with an unwavering vision. This isn’t what was happening in Florida the day that Moczydlowski showed up.

A Rivian started out as an affordable, tiny sports car, then an expensive supercar, then became an austere pickup aimed at Middle Eastern drivers scratching at life near the poverty line. None of those machines made headway and the company sputtered at the brink of insolvency. The only reason Rivian isn’t on the scrapheap of automotive history – the only reason its investment bankers are claiming it’s worth more than Ford Motor Co. – is its adaptability.

“One of the most important human characteristics … for progress, for creating improved environments, is humility and the ability to listen to others,” Scaringe said last month. His reactions to the wants of others resulted in Rivian’s 12-year gestation, which began at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

In the mid-2000s, the school’s Sloan Automotive Laboratory housed a silver 1976 Porsche 914 that graduate students were converting into an electric vehicle. Scaringe, a doctoral candidate from Rockledge, Florida, walked by the car nearly every day, but scarcely touched it.

Instead, Scaringe spent his time trying to perfect exhaust-gas recirculation and valve timing, and taking manufacturing courses. “He wasn’t an electric guy,” said classmate Emmanuel Kasseris. “He was a car guy.”

On Feb. 4, 2009, his final year, Scaringe showed up for a seminar by Daniel Roos and James Womack, faculty members and authors of a sweeping automotive history, “The Machine That Changed the World.” “It was at the end of the first class,” Womack said. “He walks up to me and says, ‘I’ve got a new idea for a car company. Let me tell you about it.’”

Degree in hand, Scaringe went home to Florida to start it. He may have learned manufacturing in a classroom, but his entrepreneurial model was close to home. His father, Robert, is also an engineer, with a scrappy shop called Mainstream Engineering. There, the elder Scaringe invents stuff largely for the Department of Defense: diesel engines, water-processing units and a system to make medical-grade oxygen from ambient air, to name a few.

R.J. Scaringe set up shop in the same cluster of buildings, naming his own endeavor Mainstream Motors. Scaringe has said he didn’t fully understand the complexities ahead. “A very low probability of success,” he admitted in an internal video last year.

“The only way to start was to start,” he said on a podcast in February 2020. “Lots of U-turns, lots of twists, lots of turns, lots of gut punches. Overall, just brute force built it.”

Scaringe recruited about 15 designers and engineers who bought into his vision: a sports car that combined high performance and fuel efficiency with a low price.

They were a fiercely committed bunch. Brian Gase, the fourth employee, said he left his job interview thinking “these people are crazy. They believe they can do something they don’t know how to do, and I was hooked.”

Scaringe didn’t think he could sell more than about 40,000 cars a year. With cagey manufacturing and lightweight materials, he wouldn’t charge more than $25,000.

Instead of a steel frame, he would use lightweight aluminum. Instead of steel body panels, Scaringe envisioned thermoplastic sheets. Mainstream would piece together its coupe in four modules, like a kid’s toy. There would be no metal-stamping machines and no paint shop — two of the most expensive parts of any conventional plant.

The team worked incessantly, once stringing together four consecutive all-nighters. Scaringe would take everybody to lunch on Fridays and every winter, they would decamp to Daytona to watch a 24-hour race, bleary-eyed amid the screaming engines.

“It truly was tribal,” said Renee Templeton, former head of human resources. “I’m not even sure everyone had job titles.”

After about a year, the tribe had plans for a prototype; the engine was an afterthought. Scaringe shipped the files to a contract manufacturer in Detroit, along with a Mini Cooper. The instructions, according to Chris Auerbach, a seminal employee, were to build the car, plop in the Mini’s engine and send back the whole package in a crate.

The prototype, dubbed “the Blue Thing,” rolled off the truck in Florida in fall 2010. A photo marking the occasion shows the team with wide grins that belie reality: The car was nowhere near ready for production, or even driving. It looked like a Honda hatchback in a gawky teenage phase.

Nevertheless, a car is a car, and the Blue Thing would serve for pitching investors.

Scaringe organized a brain trust including Jim Thomas, a former chief finance officer at MapQuest, and Rick Wagoner, a former chief executive officer of General Motors Co.

Doors were opened, the calendar was scattered with meetings, but nothing was taking hold. Scaringe and his father mortgaged their homes and rounded up $3.5 million in state funding. Employees agreed to house interns who’d gone to work for the startup. Raises were out of the question and the weekly snack budget was about $35.

“We didn’t have money,” Templeton recalls. “We just didn’t have it.”

The machine Scaringe had so confidently conceived began to buckle under the financial pressure. “Week to week, month to month, the whole plan would change,” Moczydlowski said. “It was really just a circular pattern: Let’s design something, pitch it to an investor and, you know, kind of rinse and repeat.”

At one point, the team was working on a spartan race car to woo a Brazilian investor. Then, they shifted to a higher-performance, higher-price version of their original idea.

“Pivots didn’t cost much money,” Womack said.

Moczydlowski was laid off in February 2012, shortly before several co-workers. Auerbach decamped to culinary school.

In the tumult, two words seldom arose: “electric” and “truck.”

Scaringe had set out to build a performance vehicle, and “if you’re looking at a sports car market, people were so afraid to lose the sound and smell of exhaust,” Auerbach said.

But Scaringe just wanted to build something — it didn’t much matter what it looked like, or even what it was called. Mainstream became Averra became Rivian, inspired by the Indian River near Rockledge.

Ultimately, that MIT seminar paid off. Roos, the professor, was good friends with Mohammed Abdul Latif Jameel, an MIT alumnus and CEO of Abdul Latif Jameel, which owns car dealerships from Europe to Japan. Scaringe called in a favor.

A few months later, he was sitting on a rug in the Saudi Arabian desert, surrounded by smoky hookahs and dusty Toyotas. Over tea and sweets, Jameel’s son, Hassan, gave Scaringe homework: Design an efficient, rugged pickup — the lovechild of a Ford F-150, a Toyota Prius and a dune buggy.

Around year-end, Scaringe sent ALJ rough plans, and the company agreed to invest a nominal amount, but nevertheless a lifeline for the frantic Florida skunkworks. By the time Rivian decamped to Detroit a few months later, there were fewer than 10 employees.

Spartan and stamped out in high volume, the desert machine would be at odds with Scaringe’s original concept: a precious piece of engineering for automotive savants. The truck part, however, was Scaringe’s long-shot chance.

“Shifting from the coupe to the truck space was our darkest moment,” Gase said.

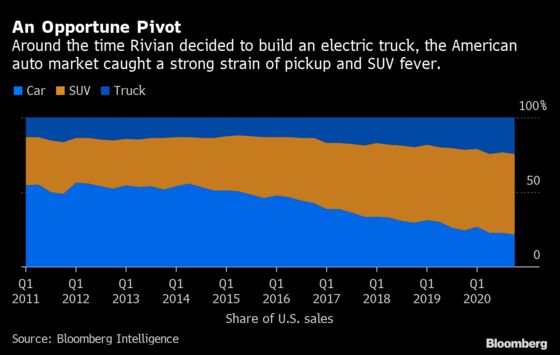

Ever-plusher pickups had long been the U.S. auto industry’s most profitable slice, with General Motors, Ford and the former Chrysler Group netting more than $10,000 in profit per machine. American tastes were spreading across the globe.

ALJ, by then a major investor, shelved the desert truck idea and agreed to a more opulent pickup. Still, Scaringe needed something to make Rivian’s machines drastically different — sexier — than the other rigs coming out of Detroit.

“He announced it at a board meeting one day,” Womack said. “No one was expecting it: ‘I’ve made the decision this will be an all-electric vehicle. We don’t need to discuss this further.’”

By November 2018, Rivian had two prototypes to reveal, a pickup and an SUV. The singer Rihanna, then Hassan’s girlfriend, did the honors at an annual Los Angeles auto show.

“My first impressions were that it looks really cool,” said IHS Markit analyst Stephanie Brinley. “It looks like a truck, but it’s different; it does a really good job of communicating its technology.”

Orders began pouring in. They have since climbed to over 48,000, according to the company’s S-1 filing.

The woman Scaringe was chasing in that long-ago race is now his wife. His marathon with Rivian, in many ways, has just begun, and it won’t be easy.

The startup may do for pickup trucks and SUVs what Tesla did for the family sedan. But the market for electric trucks and SUVs has steadily shrunk as the incumbent auto giants have fast-tracked plans for their own battery-powered workhorses. General Motor’s GMC Hummer EV, an $80,000 rival, has already been spotted in the wild. And Ford recently doubled production plans for its electric F-150 Lightning, due out next year, saying it has surpassed 150,000 reservations.

To succeed, Rivian’s vehicles will have to not just be novel, but great. The first iterations rolling into the world have won praise, but also display technical gremlins, including rogue windshield wipers and an adaptive cruise control system on the blink. The company is barreling towards Wall Street with almost $1 billion in net losses in the first half of the year, according to the SEC filing. Meanwhile, the ranks of expectant customers are getting restless.

But Scaringe is beginning to find his footing and, true to form, he's running at full speed. He's also limping a little bit, too.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.