Risky Company Debt Is Getting Riskier

Risky Company Debt Is Getting Riskier

(Bloomberg Markets) -- One night in 1982, a group of bankers from Drexel Burnham Lambert gathered at the Quilted Giraffe, a nouvelle cuisine restaurant in New York frequented by Warren Beatty and Jackie Onassis.

The financiers were there to celebrate a junk-bond deal that got away. They’d worked with Sparkman Energy Corp. for months, but the natural gas pipeline company had stopped returning their calls. Contractual terms that Drexel was proposing for the bond, particularly investor protections known as covenants, had been deemed too strict, says Vince Pisano, an attorney who worked on the deal.

At the dinner, Pisano recalls, some bankers wore custom-made belt buckles that featured Sparkman’s logo—crossed out with a slash. They were luckier than they realized at the time. Five years later, Chairman Wallace Sparkman would reach a settlement with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, neither confirming nor denying participating in an alleged kickback scheme.

Few at the dinner recognized that Sparkman’s decision to insist on looser bond terms was a sign of what would come decades later. The legal framework that Pisano and his colleagues were creating in the 1980s helped fortify what would become a more than $2 trillion market in junk bonds and loans. But in the last few years, that framework of covenants, once routine for the riskiest borrowers, has come under severe attack.

Private equity firms such as Apollo Global Management and KKR & Co. have fought to make it easier for the companies they own to take on more debt soon after borrowing, and for debtors to sell off assets and pay the proceeds to shareholders. For a decade they had already chipped away at other provisions in loans known as “maintenance covenants”—requirements that a corporate borrower meet specific performance hurdles or else be forced to renegotiate terms or even repay debt.

Private equity firms “began to select their investment banks based in part on who could get the loosest high-yield covenants,” says Kirk Davenport, a former partner at law firm Latham & Watkins who also worked for Drexel on early junk-bond deals. “And once they figured that out, the race to the bottom was on.”

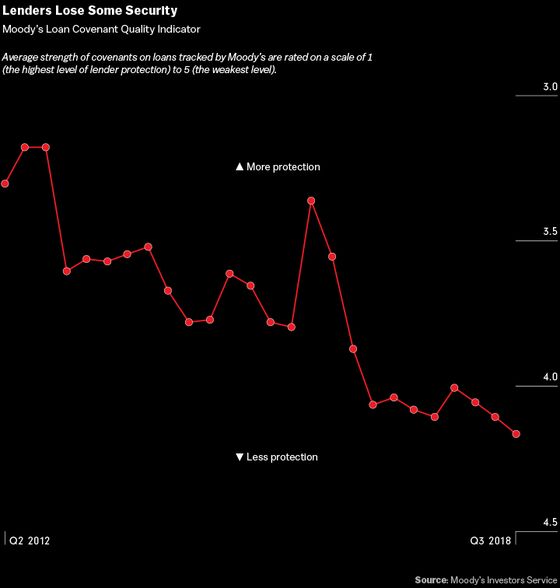

Moody’s Investors Service says covenants for bonds and loans generally are at or near their weakest levels since the ratings firm started tracking them nearly a decade ago. When the economy slows, lenders could suffer much bigger losses than in previous downturns, say strategists at UBS Group AG, who estimate that lenders might recover less than half their money instead of 75 percent to 80 percent because of eroded protections.

Lenders to Caesars Entertainment Operating Co., the casino company that filed for bankruptcy in 2015, are familiar with this problem. The company changed its covenants in 2014 when it took out a $1.75 billion loan, raising the limit on how much debt it could take on that would give lenders a first claim on assets if the company went under. The new covenants helped allow Apollo and TPG Capital LP, the private equity firms that bought Caesars in 2008, to strip assets from creditors’ reach before the casino company went under, a court-appointed bankruptcy firm found in 2016. A spokesman for Apollo declined to comment.

Investors complained about the terms on a series of bond and loan sales last year, but they still bought the debt. In one September sale, KKR & Co. helped finance its buyout of Envision Healthcare Corp. with debt that contained provisions making it easy for KKR to sell the most profitable portion of the company’s business, leaving lenders with the less attractive part. KKR declined to comment.

Private equity firms and their lawyers often note that not having maintenance covenants gives a company more leeway to survive a stumble. Otherwise lenders, entitled to demand higher interest at the first sign of weakness, might push the borrower into bankruptcy in the rush to recover their money.

“A number of companies have gone from being a high-yield issuer and back to investment grade because they have been allowed to operate their business in a way that an inflexible covenant package would have prohibited them from doing,” says William Hartnett, a partner at law firm Cahill Gordon & Reindel LLP who also represented Drexel on its early deals.

Covenants were once required mainly by banks’ loan departments, which were armed with workout teams that specialized in squeezing more money out of troubled companies to ensure the lenders got paid back as much as possible. Strong covenants can be a real advantage in those situations. Institutional investors, which today account for most of the loan market, are more likely to sell out fast instead of sticking with a distressed borrower. According to S&P Global Market Intelligence’s LCD unit, almost 80 percent of the outstanding loans in the market lack maintenance covenants, in deals dubbed “covenant lite.”

“No one wants a company to default,” says Thomas Majewski, managing partner and founder of Eagle Point Credit Management, which manages $2.6 billion. “With covenant lite, we believe there will be fewer defaults and we expect those to happen later, so we will still receive our interest.”

Still, weaker covenants have emboldened companies to take steps that aren’t purely about survival. Some strip away collateral before a default to benefit equity investors at the expense of lenders. In 2017, preppy clothing retailer J.Crew Group Inc. moved its valuable trademarks out of the reach of creditors when it restructured debt. As decades-long norms that were once spelled out in contracts are eroded, lenders and equity investors increasingly find themselves clashing in courts. “Lenders may need to resort to the courts more and more in the next downturn,” says Michael Nechamkin of Octagon Credit Investors. —With Davide Scigliuzzo

Bakewell and Lee cover corporate finance and leveraged lending for Bloomberg News in New York.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Christine Harper at charper@bloomberg.net, Dan Wilchins

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.