Riskiest CLO Pieces Signal Years of Corporate Pain Ahead

Riskiest CLO Pieces Signal Years of Corporate Pain Ahead

(Bloomberg) -- The riskiest parts of the $700 billion collateralized loan obligation market are signaling a tough road ahead for U.S. companies, with a wave of bankruptcies potentially spanning years.

Investments known as CLO equity have lost a quarter of their value this year, and asset managers including Oaktree Capital Management and Gateway Credit Partners are skeptical that they will turn around anytime soon. The instruments are the first to sustain losses when the debt backing CLOs -- risky loans to highly leveraged companies -- starts going bad.

If a surge in bankruptcies lasts for just a year or two, as in the last crisis, CLO equity can perform well. The money managers overseeing CLO loan portfolios can sell bad assets and buy better ones that bounce back as the economy recovers. In 2010, the equity returns averaged around 20%.

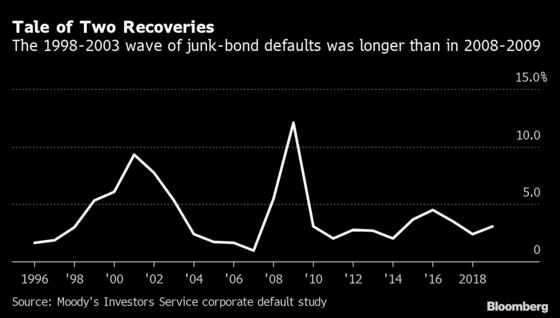

But the big drop in CLO equity this year signals investor fear that this downturn will be more like the 1998 to 2003 period, where company defaults rise and stay elevated over the course of years, and profiting from improving prices in loans is hard. That’s why many money managers are shifting into safer CLO debt, which is later in line to take a hit when companies fail. Bankruptcies are already jumping, and a key quarterly CLO payout date this month will tell investors how bad the damage has been.

“Dislocations are not always a great opportunity for CLOs,” said Brendan Beer, an Oaktree portfolio manager. “If things don’t go well, losses pile up.”

Looming Pain

There are other signs that more trouble is looming for U.S. companies. JPMorgan Chase & Co., Wells Fargo & Co. and Citigroup Inc. said this week they put aside a total of around $28 billion in the second quarter to cover expected future losses in corporate and consumer debt, an eye-popping figure. Edward Altman, who created the widely-used Z-score model for predicting corporate bankruptcies, said this week that the spate of “mega” insolvencies that started this year is just getting started.

CLO equity has always been high risk, and typically also came with high rewards. Instruments originally sold in 2007, for example, generated internal rates of return of 22% in 2008, 5.5% in 2009, and 20% in 2010, according to Morgan Stanley. In 2016, equity dating from 2011 gained 62%.

But a series of stars have to align to generate those kinds of returns. CLOs are designed to ensure that the holders of their safest debt, the notes rated AAA, are protected when the loans in the underlying portfolio start deteriorating. When too many loans get downgraded into the CCC tier, the CLO often has to stop making payments to equity holders and shunt that money to holders of their safest obligations.

About 30% of CLOs are forecast to have faced enough loan downgrades by July, or failed some other performance test, to potentially trip that safeguard, according to Deutsche Bank AG research. But the CLOs can sell off their CCC rated loans to avoid skipping payments to equity, so only about 18% of the deals have cut off payments, the bank wrote.

Down, Then Up

CLO portfolios that have more than 7.5% of their loans rated in the CCC tier have to start writing down the value of some investments. If an asset manager gets rid of enough CCC loans trading below 80 cents on the dollar or so -- especially ones that are unlikely to rebound in price -- and buys more debt above that price, it can potentially bring a deal back into compliance with performance tests, thanks to a quirk in CLO accounting. Loans that are priced at about 80 cents on the dollar or higher can usually be recorded on the asset manager’s books as being worth 100 cents on the dollar, for the purposes of satisfying compliance tests.

That means CLO managers are hopeful that economic conditions remain strong enough for relatively weak companies to continue paying their obligations. In the near term they also want loan prices to stay depressed, or even fall further, to create more potential bargains. Over time, the investors profit if more and more loans recover.

“Every loan will either default or pay off at par,” said Tom Majewski, a partner and founder at Eagle Point Credit Management. “We hope that they will trade down for awhile and then pay off at par. That’s the best situation, and that’s what happened in 2008.”

Despite the uncertainty, some investors believe there are bargains to be found in CLO equity. Olga Chernova, chief investment officer at Sancus Capital Management, forecasts a huge range of possible internal rates of return for CLO equity, from -15% to 39.75%, with a middle ground ranging from 3.89% to 17.4%.

“Equity is trading with a huge dispersion and generalizing deals is completely impossible,” Chernova said. “You have to do the bottom-up work and figure out the value.”

Numerous asset managers, including Napier Park Global Capital, Neuberger Berman, Octagon Credit Investors and DFG Investment Advisers have been focusing on buying so-called mezzanine CLO debt, in the BBB, BB, and B tiers, which they believe has a better chance of rebounding in price and delivering long-term value. In fact, a Credit Suisse Asset Management CLO equity fund established late last year expanded its scope earlier this year to buy BB rated debt.

CLO managers will probably have widely varying outcomes, based on how well they can navigate the recession and trade their portfolios, said Serhan Secmen, a portfolio manager and head of U.S. CLO investments at Napier Park.

“A lot depends on the manager,” Secmen said.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.