Rejoining Paris Would Be Easy for Biden. The Hard Part Is Averting Climate Disaster

Rejoining Paris Would Be Easy for Biden. The Hard Part Is Averting Climate Disaster

(Bloomberg) -- For a President Joe Biden, rejoining the Paris Agreement would be almost as simple as signing an autograph. The hard part would be everything else.

With global warming already fueling wildfires, hurricanes and mass migrations, Biden would face the monumental task of decarbonizing the world’s biggest economy. And he would have to do it quickly at a time when China, the biggest emitter of greenhouse gases, is recasting itself as a climate leader and as the European Union ramps up its environmental ambitions. The stakes are high: Failure would not only erode global confidence in the U.S. but contribute further to the destabilization of the climate, with grave consequences for people and planet.

It’s a far cry from where things stood in 2015, when President Barack Obama signed the pact and climate leaders were hopeful that it could stem a catastrophic rise in global temperatures. Since then, President Donald Trump has pulled out of the agreement – a move that will become official on Nov. 4 – and dismantled many of his predecessor’s climate policies.

That would put Biden, who on Tuesday faced Trump in their first presidential debate, in the position of both having to win back international support and build a climate policy infrastructure from the ground up if he’s elected.

“There is a question of what do you bring back to the table and how do you establish trust,” said Joseph Majkut, director of climate policy at the Niskanen Center, a Washington-based think tank. “To buy back into the game might require more ambition or maybe some more domestic policy changes.”

The Paris Agreement, a landmark accord with 195 signatories, allows members to set their own emissions targets. Under Obama, the U.S. pledged to curb greenhouse gas emissions by 26-28% below 2005 levels by 2025. Under Trump, the U.S. discarded that commitment and is no longer on track to meet those goals, according to David Victor, a professor of international relations at the University of California at San Diego.

Biden has said he would rejoin the pact if elected. That would only require the U.S. to notify the United Nations, with re-entry active 30 days later. The U.S. also would need to submit a specific pledge to reduce emissions, known as a Nationally Determined Contribution.

The stark divide over the agreement was highlighted during Tuesday’s debate. Biden reiterated his plan to rejoin the accord, saying it’s “all falling apart” without the U.S. Trump, meanwhile, called the Paris plan a “disaster” and said people were happy being out of it.

Biden has already proposed a sweeping climate plan that could lay the foundation for a new emissions pledge. The $2 trillion, clean-energy and infrastructure proposal calls for an emissions-free electric grid in 15 years, and includes a target of net-zero emissions across the entire economy by 2050. It’s one of the most ambitious climate proposals in the world, surpassing China’s recently announced goal of being carbon neutral by 2060.

Achieving it would be challenging, but Biden could quickly build a domestic climate program by spinning forward Obama-era rules, such as fuel efficiency standards that would accelerate the adoption of electric vehicles, and by crafting federal versions of existing state policies governing clean power. He’s also pledged to “fully integrate climate change into our foreign policy and national security strategies, as well as our approach to trade,” according to his campaign website.

How exactly he would do so remains an open question. U.S. policy to date has largely been “shallow decarbonization,” with modest achievements that won’t be enough to head off the worst impact of climate change, said Victor. “Deep decarbonization will require an economy-wide effort.”

Biden’s most obvious options for doing that rest in Washington, where much is currently up in the air. Creating a national carbon-pricing market or adopting clean-energy tax incentives could begin cleaning up swathes of the economy, but both would require congressional approval. That may prove difficult, even impossible, if Republicans retain control of the Senate after the election.

The U.S.’s commitment to the UN’s Green Climate Fund, which is key to helping developing nations cut emissions, faces the same challenge. While Biden could call on State Department funds to fulfill a sliver of the $3 billion U.S. pledge, according to Alice Hill, senior fellow for energy and the environment at the Council on Foreign Relations, meeting the full commitment would require getting an appropriation through a divided Congress at a time when lawmakers are focused on domestic priorities such as support for jobs and Covid-19 relief.

Like Obama, Biden could pursue his priorities by flexing the power of the executive branch. To do that, he’ll need an “entire policy apparatus that puts climate concerns at the forefront” of agencies including the Environmental Protection Agency and the departments of Energy, Interior and Treasury, said Jeff Hauser, director of the Revolving Door Project.

But any rules his administration imposes or rewrites could be challenged in federal courts that have been reshaped with the addition of more than 200 Trump-appointed judges. Amy Coney Barrett, Trump’s pick to replace liberal Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, is expected to move the court further right on environmental and other issues if she’s confirmed.

That doesn’t mean the task is unachievable. When Trump left the Paris agreement in 2017, states and businesses stepped up their own climate efforts. At least 16 states now have 100% zero-carbon or carbon-neutral electricity goals.

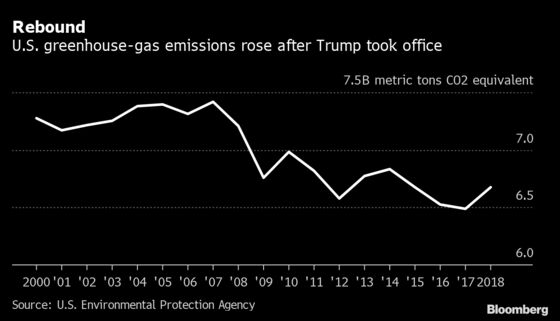

Those moves have helped to mitigate the impact of Trump’s policies. According to a report from Rhodium Group, U.S. emissions were on track to decline 4% over Trump’s first term, before the coronavirus lockdowns slowed the economy. But that’s not enough to meet even the Obama-era Paris commitments.

Still, the long-term decarbonization of the U.S. electricity and transportation sectors look feasible, said Majkut. Now, it’s a question of scale and durability, which can be encouraged at the federal level.

“Public policy allows capital to flow, secure commitments and keep things from backsliding if corporate valiance changes,” he said.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.