The Long Boom in Stocks and U.S. Economy Has a Slow-Lane Too

The Industries Propelling the S&P to Records Aren’t the Ones Driving the Economic Expansion

(Bloomberg) -- The record U.S. economic expansion and the accompanying bull market in stocks have a lot in common, being long lasting, slow burning -- and highly polarized.

Soaring values of technology companies have dominated stock gains but those businesses also embody some of the nation’s struggles over the past 10 years, including the concentration of wealth and rise of automation in the workforce. Meanwhile, some industries like energy that played a larger in economic production performed poorly.

“The polarization you’re seeing, whether it’s San Francisco house prices versus Kentucky’s, or the Average Joe’s wages versus a software engineer’s pay, is effectively reflected in the consistent out-performance of tech over broader market,” said Michael Purves, chief global strategist at Weeden & Co. “This is not 1999 -- these are earnings machines, not abstractions.”

Many of the corporate titans that have propelled the benchmark S&P 500 Index of U.S. stocks to record highs are multinational conglomerates such as Facebook Inc. and Alphabet Inc.’s Google with an ability to scale in both domestic and foreign markets. Apple Inc. shares soared more than 1,000% during this 10-year expansion, becoming the first company to hit a market value of $1 trillion.

“It’s a unique feature of American companies that they have been able to capitalize on globalization and global growth,” said Srinivas Thiruvadanthai, research director at the Jerome Levy Forecasting Center.

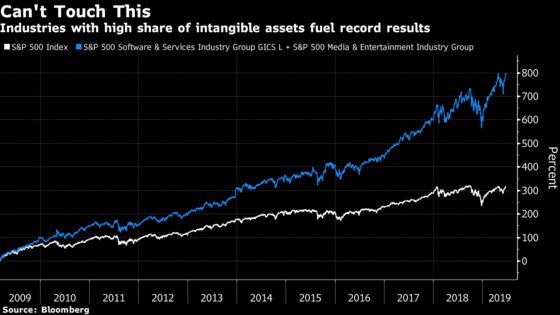

The market value of tech stocks -- software and services, plus the media and entertainment group that includes three of the FANG quartet -- has surged by nearly 800% since the bull market began in March 2009 while energy stocks have appreciated by about 50% over the time period.

The asset bases of America’s superstar market performers are more geared toward intangibles like intellectual property rather than property, plant, and physical equipment.

They’re also relatively employee scarce: the ratio of market capitalization to employment is roughly 60% higher for the software and services sector than the S&P 500 as a whole. That is, the extent to which market value is divorced from the jobs provided is particularly acute in these stocks.

Purves developed a profit measure for companies in the tech-heavy Nasdaq 100 Index, which shows that their earnings streams delivered on both quality and quantity over the past five years. Bottom-line growth has been superior and less volatile than in other industries, making the sector indispensable to generating market-beating returns.

Almost the opposite is true for sectors more linked to traditional production of tangible goods, like energy. Since the start of the expansion, U.S. oil production has grown by more than intellectual property and IP processing equipment combined -- but you wouldn’t guess that by looking at the equity market. As the U.S. became the largest energy producer in the world, the industry’s share of the S&P 500 Index by market capitalization tumbled.

That’s because the American shale revolution contributed to a glut of crude oil, which weighed on the value of energy companies the world over. The sector became a victim of its own success.

This inherent divide has led to the unthinkable, according to Karthik Sankaran, a senior strategist at Eurasia Group. It’s starting to bring together both sides of the country’s political spectrum.

“The sense that U.S. foreign and commercial policy needs to be more oriented toward protecting American workers is something that has become more bipartisan,” Sankaran said. “The biggest divide, aside from social and cultural issues, is the extent to which Democrats and Republicans want to see domestic regulation of American producers.”

For example, the parties have different approaches to prioritizing the environment over commercial interests, he said.

Fed Policy

Nonpartisan technocrats like those at the Federal Reserve may also be buying in, thanks to an “expanding palate” of reasons for dovish interest-rate policy, Sankaran added.

He pointed to recent arguments from Fed Vice Chairman Richard Clarida and Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari, who suggested that wage earners’ historically-depressed share of national income may be preventing companies from raising prices, even as labor costs are creeping up.

Companies may allow profit margins to decline from elevated levels instead of risking market share by increasing prices, which may explain why, despite tight labor markets, inflation has remained subdued. If that proves to be the case, it would turn Fed policy -- which over the last four decades has typically responded aggressively to tightening labor markets with the aim of preemptively stamping out higher inflation rates -- on its head.

Declining profit margins will add to concerns -- stoked by trade disputes -- that both stocks and the economy are running out of steam. But for now, with the stock market hitting record highs this week and a tariff truce between U.S. President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping, investors remain optimistic.

If signs of a slowdown don’t materialize and trade wars dissipate, the twin expansions may live on to fight another day, and policy makers will have gained the time needed to address the underlying challenges.

To contact the reporters on this story: Luke Kawa in New York at lkawa@bloomberg.net;Matthew Boesler in New York at mboesler1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Margaret Collins at mcollins45@bloomberg.net, Sarah McGregor

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.