(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Russia, which has the biggest budget surplus among major economies, will loosen its purse strings – but only very slightly. The government’s proposals to cautiously increase spending over the next three years are unlikely to solve President Vladimir Putin’s political problems.

Tight fiscal policies are falling out of fashion around the world. In Russia’s immediate neighborhood, budget surpluses are increasingly frowned upon. The European Central Bank is exhorting euro area governments to spend more to counteract a slowdown in growth. The Netherlands is clearly listening: It’s about to pass a stimulus budget for next year. The German government is under heavy pressure to spend more to ward off a recession. In eastern European countries that are not euro members, the ones with more expansionary fiscal policies appear to be enjoying stronger economic growth. The Czech Republic recently approved a draft 2020 budget that promises significant spending increases. On Russia’s eastern border, Japan is going for more stimulus next year. Financial resources are cheap and trade wars are creating risks for growth. Trying to boost domestic demand through increased government spending makes sense.

Based on economic data alone, Russia is even more overdue for a major spending boost than any of its neighbors. In January through August, its budget surplus reached 3.7% of gross domestic product; the government plans to bring it down to 1.7% GDP by the end of the year. Russia’s National Wellbeing Fund, which absorbs the additional revenues the government receives when the oil price is higher than $41.6 per barrel, now stands at almost $123 billion. Meanwhile, economic growth is slower than previously projected at a mere 0.9% in the second quarter. Russians’ real incomes keep dropping: In the first half of 2019, they went down 1.3% year on year. If this isn’t a case for unleashing more spending, it’s hard to say what would be.

Besides, there’s mounting political pressure for a fiscal stimulus. Putin’s popularity has sunk back to levels that preceded the annexation of Crimea, which sent his approval ratings soaring. Russians’ propensity to take part in protests stands at roughly twice the 2017 level. Moscow, the country’s capital and biggest city, is especially restive after a summer of protests that were put down with an unusual show of force. Putin is worried; in a meeting with economic officials in late August, he complained about declining incomes.

Yet the Russian government’s budget proposal for 2020 through 2022 doesn’t eliminate the budget surplus, it just lowers it to 0.8% GDP (rather than 1.2% as planned in June) and then to 0.2% in 2022. The government also has decided against tweaking the fiscal rule that diverts revenues to the National Wellbeing Fund and only allows spending from it after its size exceeds 7% GDP. That will likely happen next year, but the Russian Central Bank recommends that the government invest the excess in the global financial markets rather than inside Russia, warning that any other scenario would increase inflation risks and not necessarily lead to faster growth.

The government doesn’t appear to have much faith in its ability to spend effectively. One reason for the high budget surplus so far this year is that the funding of Putin’s 12 so-called “national projects,” aimed at delivering visible improvements to public services and infrastructure, is behind schedule. Russia’s economic managers, both in the cabinet and at the Central Bank, feel more secure supporting proven austerity policies than expansion. They’re understandably worried that any fiscal stimulus might be squandered and plundered given widespread corruption, the appetite for graft among state companies headed by Putin’s friends and the predatory behavior of Russia’s vast law enforcement apparatus.

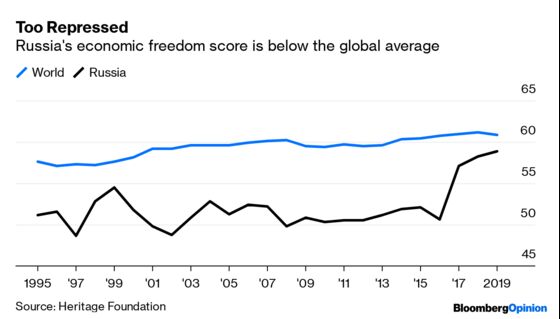

In a recent speech, Elvira Nabiullina, governor of the Central Bank, stressed that government spending, including on “national projects,” cannot lead to faster growth unless Russia’s economic climate becomes more conducive to private enterprise. “Business and not government create economic growth,” she said. Yet Russia’s level of economic freedom, as measured by the Heritage Foundation, remains below the global average.

Without oil revenues, the picture looks very different. Russia still runs a significant non-oil deficit – about 5.8% GDP this year; it’s down from 9.1% in 2016, but the government would like to reduce it to 5.5% in 2022. Russia’s oil and gas dependence continues to cast a shadow on any long-term development plans.

The caution of Russia’s economic and monetary authorities is in line with recommendations from the International Monetary Fund which said in a report published last month that “the neutral fiscal stance is appropriate, and the focus in the coming years should be on engineering a further growth-friendly shift in the composition of taxes and spending while boosting the credibility of the fiscal rule.”

Russia is just not a country where a spending boost could help the economy grow faster and make its citizens better off, despite its overflowing budget and low indebtedness (Russia’s government debt stands at about 14% of GDP, according to the IMF). Putin’s economic team continues to hold off action because it doesn’t believe in any of the available alternatives. Putin, despite his political worries, largely appears to agree: His demands for growth- and income-boosting solutions aren’t aggressive and he’s not making changes to the government lineup to signal his dissatisfaction.

This creates a window of opportunity for the anti-Putin opposition. Continued stagnation should lead to more protests; the Kremlin’s ability to suppress them will be tested more and more often in the near future.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Stephanie Baker at stebaker@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is Bloomberg Opinion's Europe columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.