Privatize Petrobras? Check With Bolsonaro's Generals First

Privatize Petrobras? Best Check With Bolsonaro's Generals First

(Bloomberg) -- Brazil’s right-wing front-runner Jair Bolsonaro became a market darling in part by promoting massive energy privatizations. But investors shouldn’t hold their breath.

Those plans are getting watered down as Bolsonaro, a former army captain who has a history of supporting economic nationalism, brings into his campaign more military officers who view oil extraction and power generation through the lens of national security. The congressman has promised to name as many as five generals to his cabinet and give the security forces their biggest public role in decades.

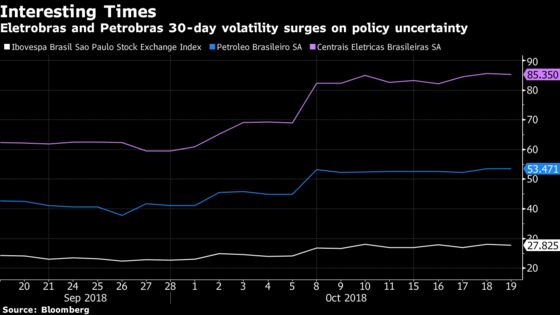

The risk for financial markets is if these generals gain the upper hand in an eventual Bolsonaro administration and sideline his top economic adviser who has pushed for privatizations of state-controlled oil producer Petrobras and power generator Eletrobras. Conflicting signals from the campaign have made shares of both companies much more volatile than Brazil’s benchmark stock index in the run-up to elections on Oct. 28.

A rupture in Bolsonaro’s relationship with Paulo Guedes, a University of Chicago-educated investor who has been the campaign’s sole voice on economic policy for the past six months, could spark a market backlash, Fitch Solutions said in a report. Shares were down 1.2 percent at 26.22 reais at 4:45 p.m. in Sao Paulo.

“Bolsonaro’s Congressional voting history displayed a clear preference for nationalist, protectionist policies that could reassert itself,” Fitch said. “A break from his market-oriented advisers could lead to a substantial shift in policy direction.”

Guedes started sharing policy objectives with these generals, who report directly to Bolsonaro, after his stronger-than-expected victory in the first round on Oct. 7. It didn’t take long for the candidate to start backtracking.

Changing Course

On Oct. 9 Bolsonaro, whose incendiary comments on race and crime draw parallels to Donald Trump, shifted course on Centrais Eletricas Brasileiras SA, as Eletrobras is known. In a televised interview, he cited concern that China would buy the company and expand its influence in Latin America’s largest economy.

He has also said the “core” of Petrobras should be preserved, a shift from Guedes’ talk of a full privatization.

“Let’s say you have a chicken coop in your backyard and live off it. When you privatize, you aren’t guaranteed a boiled egg to eat. Will we leave energy in the hands of third parties?” Bolsonaro said.

Bolsonaro’s campaign didn’t respond to an email and phone calls seeking comment.

Guedes has been calling for the privatization of almost 150 state-controlled companies including Petrobras -- a radical proposal in a country where Brazilians are emotionally attached to the oil producer as a symbol of industrial might and technological prowess.

Fernando Haddad, the left-wing contender who trails Bolsonaro in the polls, supports reversing recent industry-friendly oil legislation and is viewed as a greater risk to financial markets. Privatizations can require congressional approval and are often challenged in Brazil’s courts.

Military Administration

The Brazilian military has more experience in public administration than warfare. The army hasn’t gone to battle with another country since the 19th century and had minimal participation in World Wars I and II. General Ernesto Geisel headed Petrobras from 1969 to 1973, and then left the company to become president until 1979. The period was defined by heavy state economic intervention and widespread graft.

The military’s presence in Petroleo Brasileiro SA, as it is formally known, lasted more than 30 years after the end of dictatorship, with a general sitting on its board until 2012.

Brazil’s military has historically been divided on the state’s role in the economy, said Pedro Campos, a scholar specializing in Brazil’s dictatorship at the Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro, or UFRRJ. After being excluded from politics since democracy was restored in 1985, it is hard to predict the approach the generals will take on privatizations in the oil and power industries.

“There is no clear government program yet, and little has been put on paper. It’s a blank check,” Campos said in a telephone interview.

To contact the reporter on this story: Sabrina Valle in Rio de Janeiro at svalle@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Simon Casey at scasey4@bloomberg.net, Peter Millard

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.