Private Equity Titans Quietly Discover How to Get Richer

Private Equity Titans Quietly Discover How to Get Even Richer

(Bloomberg) -- Robert Smith built Vista Equity Partners into a money machine.

The private equity firm has racked up more than $120 billion of deals since its 2000 inception, mostly in technology companies, and produced some of the highest returns in the industry.

That has made Smith one of the world’s richest people with a $6 billion fortune. But like many private equity tycoons his wealth is largely illiquid, with the bulk of it locked up in Vista’s investment funds.

Smith, 56, pioneered an increasingly popular way to free up some of that treasure. He sold about 30% of the company he founded, helping him to become one of the most prominent philanthropists in the U.S. and buy at least $100 million of real estate, while also adding $500 million to the firm’s balance sheet.

Since cutting his first deal with Dyal Capital Partners in 2015, Smith has stepped up his philanthropy, signing Warren Buffett’s Giving Pledge in 2017. In May, he went viral with a promise to wipe out the student debt of an entire college class. He also reportedly bought two homes in Malibu, California, for about $40 million and plunked down almost $60 million on a three-story Manhattan penthouse.

Vista’s 2015 deal helped popularize sales of minority stakes, upending the conventional wisdom that only weaker businesses would sell a piece of themselves and at a time when more money than ever was pouring into private equity.

“It’s ironic that the industry has been one of the last to take private equity money,” said Daniel Adamson, senior managing director of Wafra, which was among the first to buy minority stakes in buyout firms. “It’s like a shoemaker’s family going barefoot.”

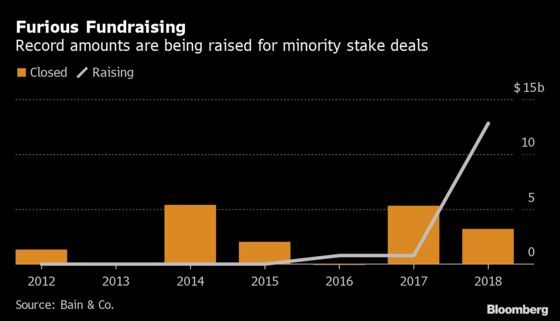

They’re making up for lost time. At least 39 buyout shops sold minority stakes from 2014 through 2018, according to a February report by Bain & Co. That’s more than triple the number from the previous five years as bulk buyers including Dyal, Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and Blackstone Group Inc. jostle for deals for established firms like Tom Gores’s Platinum Equity, Barry Sternlicht’s Starwood Capital Group and Steven Klinsky’s New Mountain Capital.

Demand is such that some are even seeding new firms, with Wafra backing a joint venture called Capital Constellation to fund promising private equity managers.

Funds targeting equity stakes raised $17 billion from 2012 through 2018 and are currently raising $17 billion more, according to Bain. Dyal’s fourth fund had raised more than $8 billion by September and already allocated most of that capital.

Meanwhile, the industry’s biggest names have been tapping some of that newfound liquidity for a variety of uses.

In 2016, Vista co-founder Brian Sheth reportedly dropped $38 million on a Los Angeles mansion and two years later spent $16 million on a neighboring property. He also has become a leading wildlife conservationist with his foundation committing $60 million largely to environmental initiatives, according to its website. He pledged more than $13 million to a youth club in Austin, Texas. David Miller, co-founder of Houston-based EnCap Investments, donated $19 million to his foundation in 2016, months after Dyal acquired 20% of his firm.

Owners and buyers stress that such deals are more about providing capital to bolster investing lines, helping general partners meet their commitments in funds they’re raising and enabling succession planning -- and typically have little to do with rewarding founders.

Typically more than 75% of the money from these investments goes back into the firms, according to a person familiar with the transactions. Vista’s Dyal deal helped it scale and boost its fund offerings without going public while Platinum Equity is using proceeds from its 2017 sale to build out a credit platform and grow its operational capabilities.

Still, the practice can generate uneasiness.

“Investors are now bracing for this kind of news,” said Andrea Auerbach, head of private investments at Cambridge Associates, which manages portfolios for endowments, foundations, pensions and family offices. “The capital can be used for lots of different things -- monetizing wealth, opening new lines of business -- and the concern is that can also take focus away from existing funds.”

Lofty Valuations

A 2018 Dyal investor presentation obtained by Bloomberg shows that seven of the 10 deals featured as case studies included some proportion of secondary sales.

No matter where the proceeds of such deals flow, the lofty valuations they bestow upon buyout shops reveal a fresh cohort of billionaires in an industry where such riches have accrued most visibly to the founders of publicly traded firms like Blackstone, KKR & Co. and Carlyle Group LP. They include Vista’s Smith and Sheth, and Starwood’s Sternlicht, according to calculations by Bloomberg.

Some scoff at such paper valuations.

“I don’t care what our firm is theoretically worth -- if I’m not going to sell the rest of it, it isn’t worth anything,” Doug Kimmelman, whose Energy Capital Partners sold a stake to Dyal in a 2017 deal, said in an interview. “It was an effective way to give us a balance sheet and strengthen the financial aspects of our firm.”

Rich Returns

Those acquiring stakes have reaped rich returns thus far. Dyal’s $5.3 billion third fund has posted annualized returns of 26% as of June 30, according to a report by the Minnesota State Board of Investment, which committed $175 million in 2016. The deals offer prized access to the economics of buyout firms at a time when private equity is steadily infiltrating just about every corner of the economy. From 24 Hour Fitness to Cinnabon to Vivid Seats, more than 20 million people are employed by the 15,000 companies backed by private equity.

“I cannot replace this kind of cash flow, predictability and downside protection,” said Christopher Zook, chairman and chief investment officer of CAZ Investments who has invested in some of Dyal’s funds. “I’ve told my wife and son that if I get hit by a bus they’re never allowed to sell this investment.”

Such optimism is well-founded. Vista’s assets have grown by more than a third to $56 billion since the second Dyal investment, making it one of the world’s biggest buyout firms. Miami-based H.I.G. Capital has added about $10 billion of assets since Dyal first invested in 2016.

Still, the market may have peaked. There’s a finite supply of top-tier firms even as the money chasing stakes in these entities grows with recent entrants including Stonyrock Partners, backed by an arm of Jefferies Financial Group Inc., and Investcorp.

“The first generation of these funds have done nicely,” said Graham Elton, Chairman of Bain’s EMEA private equity business. “They were bought well during a good period for private equity. At the time, value drivers were pointing in the right direction, but now they may no longer be doing so.”

For now, it’s giving the latest generation of private equity owners the resources that are traditionally the preserve of more liquid fortunes. That was on dramatic display earlier this year when Smith stunned students at Morehouse College’s graduation ceremony with his promise to pay off the student loans of every member of the Class of 2019, a $34 million act of largesse.

“On behalf of the eight generations of my family that have been in this country, we’re gonna put a little fuel in your bus,” he told the graduates.

--With assistance from Kiel Porter.

To contact the reporters on this story: Tom Metcalf in London at tmetcalf7@bloomberg.net;Gillian Tan in New York at gtan129@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Pierre Paulden at ppaulden@bloomberg.net, Peter Eichenbaum

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.