Powell Planted Clue to Policy Switch With 2017 Inflation Pledge

Secret behind Powell’s surprise U-turn on monetary policy can be found in comments he made in New York a year and a half ago.

(Bloomberg) -- The secret behind Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell’s surprise U-turn on monetary policy can possibly be found in comments he made in New York a year and a half ago.

Asked how he’d respond to what was then a hypothetical scenario of below target price rises and low unemployment, Powell replied: “My own view would be that we have to be committed to our 2 percent inflation mandate and we’d need to conduct monetary policy in a way that supported inflation going up.’’

And now it has -- and Powell has reacted accordingly. In a move that caught investors off-guard, he signaled last week that the Fed is done raising interest rates for at least a while. The abrupt shift left economists wondering whether muted inflation pressures will keep Fed rates on hold into the second half of 2019, even if the crosscurrents of weaker global economic growth and tighter financial conditions buffeting the U.S. subside before then.

“I would want to see a need for further rate increases and, for me, a big part of that would be inflation,’’ Powell told a Jan. 30 press conference.

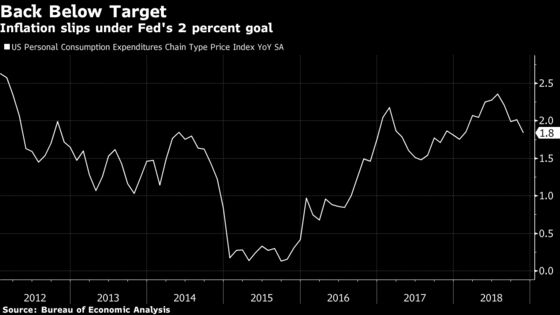

What’s unclear is how much -- and how persistent -- of an increase in inflation Powell would like to see. The Fed’s favorite inflation gauge rose 1.8 percent in November from a year earlier, down from 2.4 percent in July. Powell said it’s likely to fall further in coming months due to a drop in oil prices.

“The increased emphasis on inflation has raised the bar, but not to the point of being a prerequisite’’ for another hike, probably in the second half of the year, Goldman Sachs Group Chief Economist Jan Hatzius said in an email.

It was Hatzius who asked then-Governor Powell at a 2017 Economic Club of New York meeting how he’d respond to a late 1990s style scenario of subdued inflation and low unemployment, noting that the Fed at the time plowed ahead with rate increases.

To be sure, there are differences between then and now. Core inflation averaged 1.4 percent in 1999 versus 1.9 percent now. And the stock market back then was in bubble territory.

Today’s heightened focus on fostering faster price increases comes as the Fed is about to launch a wide-ranging public review of its practices, including how best to achieve its inflation goal.

Allianz SE chief economic adviser Mohamed El-Erian sees the Fed on hold for the entire year, restrained from raising rates by economic weakness overseas, the absence of an inflation threat and hesitation to re-ignite financial market volatility that followed its December hike.

That “gives investors more confidence to re-engage in the market,” the Bloomberg Opinion columnist said.

Fed policy makers have been puzzled for a while about why inflation hasn’t risen given how far unemployment has fallen. Joblessness was 4 percent in January, below officials’ 4.4 percent median estimate in December of the non-inflationary natural level.

This “has confounded economists and policy makers over the past several years,’’ Kansas City Fed President Esther George said Jan. 15. It raises questions about “whether the economy can operate at a lower unemployment rate today than in the past without sparking inflationary pressures.’’

Ethan Harris, head of global economics research at Bank of America Merrill Lynch, said that wages are rising in response to low unemployment. But so far at least, that hasn’t led to faster inflation.

“Wage increases do not need to be inflationary,’’ Powell told a Dec. 19 press conference, pointing to the late 1990s experience as an example.

Former Fed Chair Janet Yellen though cautioned that policy makers should not forget a lesson of the past: Very low unemployment can spur higher inflation. But with interest rates now in neutral territory where they neither spur nor restrain growth, the central bank can afford to be patient, she said.

“We’re not seeing strong inflationary pressures, if any,’’ Powell’s predecessor told CNBC on Feb. 6.

In fact, Fed policy makers have voiced concern that years of below target price rises may have lowered inflation expectations beneath 2 percent. That gives them an added incentive to seek stepped-up price rises.

“Some measures of longer-term inflation expectations in the U.S. have edged lower in recent years,’’ Powell said last year in Portugal, adding, “We haven’t really seen inflation expectations get up to 2 percent yet.’’

That matters a lot. If consumers and companies think inflation will stay low, they will act accordingly, turning that belief into a self-fulfilling prophecy.

“Because expectations of future inflation are such an important determinant of actual inflation, central banks are as much in the business of anchoring inflation expectations as they are of managing actual inflation,’’ Fed Vice Chairman Richard Clarida said in a Jan. 10 speech.

Powell told reporters in December that the Fed wasn’t ready to declare victory in achieving its price target.

“The only way to achieve inflation symmetrically around 2 percent is to have inflation symmetrically around 2 percent, and we’ve been close to that but we haven’t gotten there yet,’’ he said. “That remains to be accomplished.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Rich Miller in Washington at rmiller28@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Alister Bull at abull7@bloomberg.net, Sarah McGregor

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.