Poland and Hungary Are Right to Fear the EU’s Green Deal

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- One could regard eastern European countries’ opposition to Ursula von der Leyen’s ambitious goal of climate neutrality by 2050 as a cynical play for more financial support, and that wouldn’t be entirely wrong.

But it’s also important to recognize that these nations need firm guarantees from the European Commission president that their wealthier neighbors will help with transition costs. Otherwise, even if eastern Europe signs up to the climate pledge, her neutrality goal simply won’t be reached.

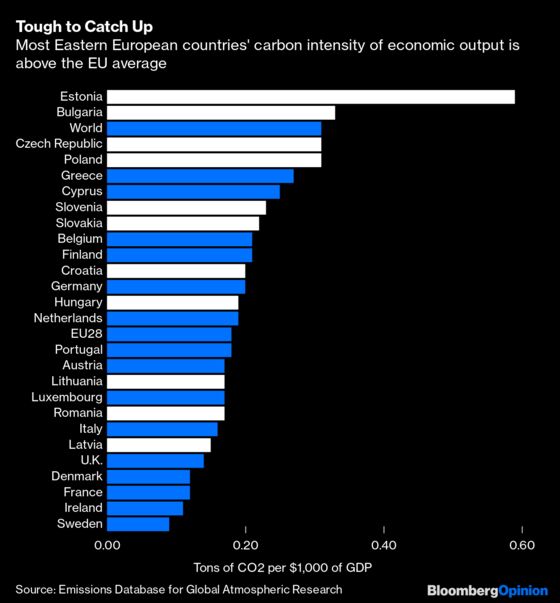

Everyone, including the Commission in its proposed Green Deal, recognizes that European Union members face unequal starting conditions. Four eastern European economies would need to get to carbon neutrality from the highest CO2 intensity of economic output in Europe; Estonia and Bulgaria have more carbon-intensive economies than the global average.

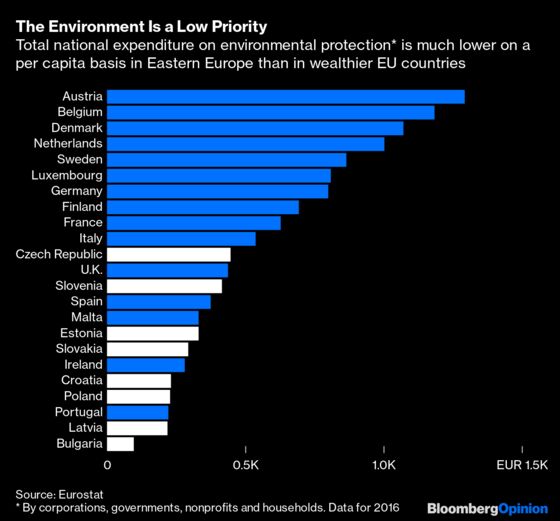

These countries have, to some extent, sacrificed environmental protections in the race to catch up to western living standards. They still have a long way to go, and they’re way behind richer nations on green spending.

Recycling rates are a good indication of how this under-investment has affected environmental conditions in Europe’s post-Communist nations. Romania recycles just 14% of its municipal waste, compared with Germany’s 68%.

Economists who have looked into the relationship between economic growth and emissions have discovered that the curve describing it is, generally, N-shaped: Emissions grow relative to gross domestic product until a certain wealth level is reached, then decline because a country can afford more advanced, less energy-intensive technology; they then start increasing again because technology can no longer compensate for an economy’s surging energy needs.

Different eastern European countries appear to be at different stages of this curve. In Bulgaria, Estonia and Lithuania, the technology effect hasn’t kicked in yet and emissions grow as the economies grow. In the Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary and Slovakia, growth doesn’t lead to increases in emissions. But almost all eastern European countries will need more green investment than their wealthier neighbors.

For those countries that dare to bargain with Brussels — Hungary, the Czech Republic and Poland — the time to do that is now. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, the boldest haggler, says his nation will need 150 billion euros ($167 billion) to become climate neutral. The Polish Economic Institute, which develops policies for the country’s nationalist government, has proposed that the EU set up a Just Energy Transition Fund of between 10 and 20 billion euros a year. At the midpoint of that range, Poland, according to the institute’s proposal, would be the biggest recipient of the fund’s money at 2.1 billion euros a year. The Czech prime minister Andrej Babis estimates his country’s costs at 675 billion korunas ($29.4 billion), or less than 1 billion euros a year.

These aren’t unmanageable amounts for the EU, but they’re significant compared with its 2019 budget of 165.8 billion euros. In June, Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Estonia vetoed the formal adoption of climate neutrality by 2050 as an EU goal. In October, Estonia caved, deciding to trust the EU to help it out. But the other three have held out, fearing that Brussels would simply relabel some of their existing subsidies as climate-related.

Von der Leyen says she wants to raise 100 billion euros to help the energy transition “in the most vulnerable regions and sectors.” Over 30 years, that’s far less than the Polish proposal. In any case, in the absence of specifics, it’s hard for countries that don’t expect to fund their transitions alone to sign up to her headline goal.

Those, like Estonia, that have already done so are merely making a political gesture, not wanting to poison Von der Leyen’s first weeks because that might be counterproductive as the EU budget for 2021 through 2027 is negotiated. On the other hand, the Poles, the Czechs and the Hungarians feel their negotiating power could wane if they backed Von der Leyen’s plan before climate transition aid is included in that budget.

It’s understandable that Von der Leyen wants EU member states to agree on priority goals first and details second. But she won’t be around in 2050 to take responsibility for any failure to reach that goal. The eastern European leaders, by contrast, are already on the hook to show their nationalist constituencies what’s in this Green Deal for them. If they cave, that won’t make climate neutrality by 2050 any more likely than if they stay firm.

It might be better for Von der Leyen to moderate the climate neutrality ambition for now. Once the budgetary details are thrashed out, her “man on the moon” ambition for the Green Deal will look more convincing, the result of careful planning and negotiation rather than a loud political statement.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is Bloomberg Opinion's Europe columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.