(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The one thing everyone involved in the bankruptcy of PG&E Corp. dreaded was another big fire sparked by the utility’s wires. It is possible that day has arrived. And while that is a big deal for the bankruptcy, we shouldn’t forget that chapter 11 is supposed to be just a way station, not an end point.

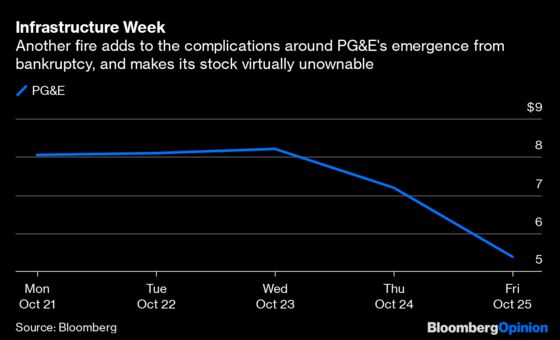

It’s important to state up front that both the cause and the ultimate extent of the Kincade Fire that broke out in northern California late Wednesday are unknown. Still, the failure of some PG&E equipment in the area just before first reports of the fire isn’t a good sign. In any case, investors shot first and asked questions later: The stock fell 12% on Thursday before the company reported equipment damage, and then slumped another 25% on Friday morning, to less than $5.50.

Back up all of four months to late June, when PG&E’s stock hit a chapter-11 peak of almost $24. At that point, investors were giddy at the prospect of California’s legislators allowing the company to cobble together various bits of financial engineering to avoid doing the obvious: recapitalizing itself with new, dilutive equity. As I wrote then, though, the scale — and, crucially, longevity — of California’s wildfire problem meant PG&E needed new money, and lots of it, rather than new encumbrances on its revenue.

Since then, the illusion of shareholders somehow just skirting by all this has been steadily stripped away. First, Sacramento rejected the company’s securitization idea and PG&E adjusted plans to incorporate a rights issue, conceding the need for a hefty amount of new money. Then, victims of 2017’s Tubbs Fire won the right to have their claims considered in court, potentially adding billions to PG&E’s liabilities. The court then took away the company’s exclusive control of the bankruptcy process, providing an opening for a rival proposal from unsecured bondholders and a group representing wildfire claimants that would all but wipe out existing shareholders. And then, of course, wildfire season arrived, bringing with it unprecedented preemptive blackouts to prevent fires — and, now, an actual fire.

Any claims arising from the Kincade fire would come in ahead of existing bondholders; PG&E’s (defaulted) bonds duly took a notable dip on Friday. While PG&E has some insurance cover and could tap the newly created wildfire insurance fund to a limited degree (limited even further if it was found to have acted imprudently), its already denuded equity value leaves little room to absorb extra liabilities. As of writing this, PG&E’s market cap is a mere $2.8 billion; hence the volatility.

An added wrinkle is that the competing multi-billion-dollar exit plans to get PG&E out of chapter 11 effectively have an out if there are more grid-linked wildfires in the meantime that destroy 500 or more properties. As of early Friday morning Pacific time, the California Department of Forestry & Fire Protection (CalFire) reported 49 structures destroyed, but only 5% of the fire contained.

It’s possible that even if this fire exceeds exit-plan thresholds, and PG&E is found liable, financiers might adjust and kick in more money. The bondholder group, in particular, gains leverage as PG&E’s stock price shrinks.

But this collapse also raises bigger questions extending beyond the bankruptcy battle. Fast forward to this time next year and assume PG&E has emerged from chapter 11. At that point, it will still be in the early part of what is likely at least a decade-long process of hardening its grid against California’s elevated (and rising) risk of wildfires. True, the state’s insurance fund will be in place, alleviating some of that. Yet the utility would likely still find itself in an uncomfortable position. The backlash to recent precautionary blackouts — from darkened neighborhoods all the way up to the governor’s mansion — underscores the point that PG&E’s tools for managing wildfire risk are, at least for now, blunt and costly with customers, regulators and politicians. Whenever the next wildfire happens, I suspect that, even under new management, PG&E would find itself subject to scathing criticism from politicians and potentially severe regulatory treatment.

This isn’t to excuse PG&E’s litany of failings. It is merely to raise a point that has been lurking under this crisis all along: Just how investible is a company tasked with providing reliable power from Silicon Valley to the foothills of the Sierra Nevada while also being on on the hook, notwithstanding a finite insurance pool, for paying out on the encroaching ravages of climate change?

Andy DeVries at CreditSights has questioned in recent reports who will actually be willing to buy the billions of dollars of new parent-level debt envisaged by the competing exit plans, which would be subordinated in any future bankruptcy and dependent on dividends from the utility subsidiary. On the equity side, when you buy a U.S. utility stock, you just don’t expect to run months-long risks of it air-dropping on a daily basis because of headlines about blackouts, wildfires or a combination of the two.

When it comes to both transparently framing and equitably distributing the costs of climate change, California is still far from having a comprehensive plan. The fact that a widely distrusted, bankrupt utility still sits at the nexus of the current structure is the surest sign of this. The question for investors, even post-exit, is what it would take for them to actually want to own a piece of that.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.