The Final Days of the World’s Oldest Bank

Founded in 1472 by survivors of the Black Death, Monte Paschi is now facing extinction.

(Bloomberg) -- After more than 500 years as a pillar of prosperity in the hills of Tuscany and a decade or so as a byword for dysfunction, Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena SpA appears to be entering the final chapter of its history.

A deal to carve up the nationalized bank and sell its viable assets to UniCredit SpA is currently being negotiated behind closed doors, ahead of a year-end deadline set by regulators for the Italian government to finally rid itself of the long-troubled lender.

Founded in 1472 by survivors of the Black Death, Monte Paschi is now facing extinction as the final consequence of years of cozy lending gone wrong, over-ambitious expansion and criminal behavior first revealed by Bloomberg News in 2013.

Yet with an institution that’s so entrenched in the cultural and social life of the region of Tuscany, nothing is straightforward. Monte Paschi has traditionally been the center of what the Sienese call the “groviglio armonioso” -- a “harmonious entanglement” of business and politics that remains present today. A by-election for a key parliamentary seat from Oct. 3 has become largely about the fate of the storied bank and the thousands of job cuts that will likely result.

Andrea Orcel, the new Chief Executive Officer of UniCredit and a deal-maker who’s had a hand in some of Europe’s biggest banking transactions, is facing off with the Italian government of Prime Minister Mario Draghi over the remnants of Monte Paschi. Orcel stands to gain the prize of Paschi’s 4 million customers in the wealthy regions around Siena -- if he can only avoid the rotten loans and legal risks; Draghi is seeking a stake for the state in UniCredit and a share of future returns.

Amid the high-level power plays, the entrepreneurs and social movers of the historic city are torn between wanting to preserve a centuries-old institution that’s part of their identity, and the need to move on and ensure economic growth after years of crisis followed by a harrowing pandemic.

In the days running up to the election, Tommaso Marrocchesi, the fifth-generation owner of the Bibbiano estate in Chianti Classico country, mans a campaign tent in front of Monte Paschi’s headquarters at the Palazzo Salimbeni -- a 14th century building with 19th century neo-Gothic additions. Although a political novice, Marrocchesi is fighting to take the vacant seat away from the dominant center-left Democratic Party and their candidate, former Italian prime minister Enrico Letta. He’s campaigning on a League party ticket, and against the UniCredit deal.

“Whoever allows the sale to UniCredit will have to take responsibility for killing Siena and its province,” he says.

The city-state of Siena established Monte Pio -- or “mount of piety” -- in the 15th century to make loans to local farmers, founding an institution that would help trace the development of European finance. The succeeding centuries saw activity expand throughout the rich pastures and vineyards of the region and, with Italian unification in the 19th century, elsewhere in the country.

For decades, the bank’s charitable foundation poured money into social and cultural projects. That made Monte Paschi a crucial nexus of political power, highlighted twice a year, when executives entertained clients with mounds of beef brisket and its own vintage chianti in the box overlooking Siena’s main square during the iconic Palio horse race.

The dark side of that role as “Babbo Monte” -- a pun that likens the bank to Father Christmas -- was the tens of billions of euros in unprofitable loans piled up on the balance sheet. To its critics, Monte Paschi caused its own financial disaster in the 2000s when it tried to expand too far, too fast.

A key moment was in 2007 when Chairman Giuseppe Mussari and General manager Antonio Vigni bought Banca Antonveneta SpA for 9 billion euros ($10.5 billion) in cash -- one third more than the valuation Banco Santander SA had put on it in a transaction just weeks earlier.

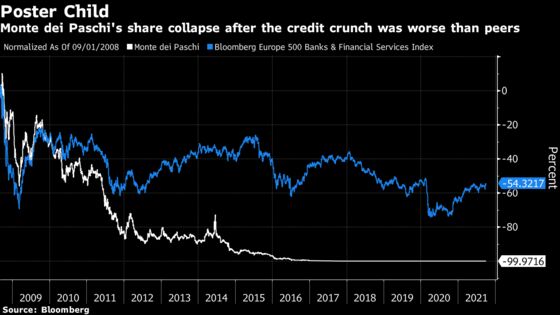

In 2009, at a time when banks around the world were starting to emerge from the post-Lehman credit crunch, Monte Paschi began its ill-fated bet on Italian sovereign debt. The bank tripled its holdings of the bonds in the years running up to the euro-area crisis.

Those mistakes augured years of austerity in Siena, as the bank cut back on lending amid successive bailouts. The revelation that executives had earlier used derivatives supplied by Deutsche Bank AG and Nomura Holdings Inc to mask losses led to criminal charges and sealed the decline.

Local businesses that had relied on Babbo Monte turned elsewhere. Now, there’s little sign of the confidence that accompanied the beef brisket on Palio day.

“The harmonious entanglement isn’t there anymore, but neither is the bank,” Marrocchesi says.

The logic that underpins the division of Monte Paschi’s assets and sale of a portion of them to UniCredit is that, standalone, the lender is not viable. In stress tests run by the European Union earlier this year, Monte Paschi emerged as the weakest institution in the region, and executives anyway acknowledge they need some 2.5 billion euros in fresh capital by next year.

In the last decade, Monte Paschi has turned an annual profit twice. It has more employees per branch, and a higher cost-to-income ratio, than almost all its rivals. At 150 billion euros, its balance sheet is a fraction of UniCredit’s, at almost a trillion euros.

“The only solution is a combination with a larger, more stable bank,” says Stefano Girola, a portfolio manager at Alicanto Capital SGR.

Businesspeople in Siena in fact talk as if Monte Paschi were a fondly-remembered relative who has already passed away.

“Paschi meant a lot to me, I dressed the wives and daughters of executives and my business revolved around the bank, its investors and politicians,” says Elisabetta Teri, 56, a fashion designer and owner of a luxury boutique in the city. “On the occasion of the Palio, I had orders for tailor-made clothes months in advance. Losing the brand would be a huge loss for Siena, as it symbolizes the long history of our region.”

There’s a second layer of history to the Monte Paschi saga. Mario Draghi is currently enjoying a honeymoon period as prime minister of Italy, with approval ratings for the former European Central Bank President often reaching 70%. His star is also high in the Brussels firmament, with European Union officials keen to support an Italian leader seen as being able to get things done.

But for Draghi, the Monte Paschi tale is a blemish on an otherwise shining career in public life. It was Draghi who, as governor of the Bank of Italy, gave his blessing to the ill-fated purchase of Banca Antonveneta SpA in 2007. By historical happenstance, as a Merrill Lynch investment banker, Andrea Orcel was also deeply involved in that deal.

Orcel’s return to Italy after decades abroad has been presaged by expectations that he will reshape the Italian banking sector with bold acquisitions. Acquiring what’s left of Monte Paschi may not have been part of his original plan though, and the executive is pushing hard to only take the good parts of the Tuscan lender if he commits to it at all, insisting that the transaction be neutral for UniCredit’s capital levels.

What’s potentially even riskier for his reputation would be the job losses that accompany a radical reshaping of the bank. Monte Paschi has some 21,000 employees, and about 2,500 are already expected to lose their jobs even if a deal with UniCredit doesn’t materialize. Those redundancies will be political poison for whomever is seen as causing them, even though the process in Italy is voluntary and eased by generous early-retirement and social support policies

“If Orcel doesn’t buy Paschi, he will be remembered as the CEO who resisted the government pressure,” says Carlo Alberto Carnevale Maffe, professor of business strategy at Bocconi University in Milan. “The reputational risks, on the other hand, are very high if he signs the deal.”

As a result, the 58-year old Orcel is treading carefully. At the Italian Finance Ministry, which will oversee the sale of the state asset and which would play a role in any future M&A transactions, the mood toward Orcel is mixed, according to people familiar with the matter. Some admire the native Roman’s charisma and international resume, while others grumble at his growing requests for a Paschi free of any and all issues for him, the people said.

As it stands, the division and demise of Monte Paschi remains a least-worst option that few of the protagonists are actually enthusiastic about. Its political status is also a paradox: The government wants to sell it to UniCredit, but none of the parties which make up the coalition backs the idea as none of them wants to take ownership of a deal which will imply thousands of job cuts.

Yet a different path for the bank may hinge on an unlikely electoral outcome in the race for the Siena seat -- a victory for the populist Northern League and their candidate Marrocchesi. While he hasn’t put forward any comprehensive alternative, he’s arguing that the lender’s books be made public and the Italian parliament to be put in charge of formulating a plan -- a step that would almost certainly kick any significant change into the political long grass.

For now, the fate of Monte Paschi appears to drift toward an oblivion that’s been foretold by years of decline.

Antonello Pianigiani runs one of the biggest native Siena businesses, an industrial waste management firm. Surrounded by the scrap metal from which he’s made his fortune, he shrugs about the cultural meaning of the bank to the city.

“We are looking at the future with a business perspective, not with our hearts,” he says. “If the brand will disappear, Siena will lose an asset, but for us nothing will change.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.