Olive Oil Makers Want to Go Gourmet, But Shoppers Aren’t Buying

Healthy-living trends were supposed to help olive oil shift upmarket, but consumers remain stubbornly price conscious.

(Bloomberg) -- In the rugged Tras-os-Montes region of northern Portugal, Vitor Baptista braves frosty mornings and long drives from his home near Lisbon to pursue the sentimental goal of transforming olive oil into something more than a condiment.

The 46-year-old construction manager started the Arvolea brand three years ago and hopes to one day devote himself full time to creating oils with almond notes and balanced acidity from his small grove of Santulhana olive trees, some of which are more than 100 years old. But his dream of breathing new life into his family’s tradition risks colliding with the cold realities of market dynamics.

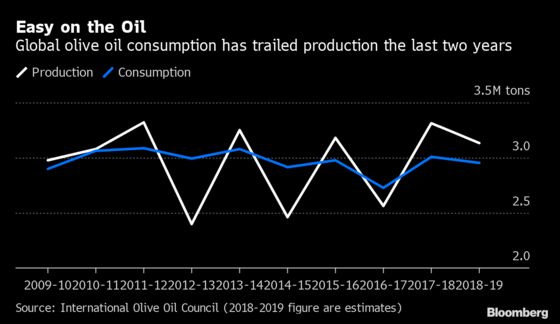

Healthy-living trends were supposed to generate a boom, but reality has fallen short. Prices are tumbling as supply exceeds demand. And big producers are joining family farms in trying to transform olive oil into a gourmet product, with protected-origin labeling, fancy bottles and tasting ateliers. That could give the trend more momentum or overwhelm it.

“The world of olive oil isn’t very different from the world of wine,” Baptista said, paging through his glossy brochure, including an oil promising a sweet entry and a spicy finish. “We bet on image and other factors that can add value,” he said, acknowledging that he couldn’t cover production costs at the prices set for the world market from vast hedge-like groves in Spain and Portugal.

There’s a romantic element to the gold-green oil, conjuring up images of sun-drenched landscapes and deep blue Mediterranean waters. Its traditions date back thousands of years, and the fruit is still harvested in rocky environs by whacking it off trees with long poles. But in the modern era, it’s a big business, shipped in tankers and sold by the ton. European Union countries exported more than $6 billion worth of olive oil in 2018.

Unlike wine, olive oil doesn’t age well and starts turning bitter after about a year. That means producers race against the clock to harvest, refine and market their wares. Also working against the effort is the fact that the oil is seldom consumed on its own, marginalizing taste nuances. And there’s of course no intoxicating effect. The upscale shift is further complicated by past allegations of the industry illicitly blending in cheaper oils.

Spain accounts for about half of all olive-oil output, and the price of the country’s extra-virgin variety dropped 33% below its five-year average this fall. That prompted the EU to intervene to address the “serious market imbalance” by offering subsidies to store oil for the short term rather than flood the market after the harvest.

Commodification is well advanced. Glencore Plc opened a trading desk in Madrid in 2015 and now handles about 12,000 tons a year, quadruple initial volumes. To support the operation, the world’s largest commodities trader recently completed a storage facility in southern Spain.

While big producers sell most of their olive oil in bulk, more are dedicating a portion of their output to select varieties that are bottled and labeled for a gourmet feel. The aims are twofold: escape the crushing price pressure and hope the upscale shift radiates across the industry.

“It’s important in terms of strategic value,” said Gabriel Trenzado, technical director at Spain’s Agro-Alimentarias Cooperative, which represents hundreds of olive growers, adding that better packaging and marketing helps sales in countries such as the U.S. and Japan. “We would like it if it were not a commodity.”

The physical manifestation of the trend is Sovena Group’s sleek mill at its giant Marmelo grove, the largest in Portugal. The smooth white structure — designed as a destination for tours and tastings for its Oliveira da Serra brand — emerges like a modernist sculpture from the tidy rows of squat green trees near Ferreira do Alentejo.

In the last several years, there’s been a surge in terroir labels for olive oil — such as Portuguese Moura, Spanish Lucena and French Nyons. But among buyers, the effort hasn’t gotten much traction in Europe or elsewhere, says Esteban Carneros, head of communications at the large olive producers’ cooperative Dcoop in Spain.

“When consumers ask for a wine, the most common thing is to ask for a designation-of-origin wine,” such as Spanish Rioja, French Beaujolais or Italian Gavi, Carneros said. “In the case of olive oil, that hasn’t happened. It’s coming along much more slowly.”

Nuno Rodrigues, a researcher who some call an enologist of olive oil, estimates it will take 20 years to educate consumers. “There’s still a long road ahead,” he said.

In Germany, supermarket chain Rewe offers high-end varieties at its big stores, but the bulk of demand is for affordable blends costing less than 10 euros a liter. “There is no real willingness to pay for higher-quality oils,” said Raimund Esser, a spokesman for the retailer.

That’s bad news for producers like Fabrizio Pini. The Italian grower grew up playing in his grandfather’s oil mill and now runs a facility near Rome. He presses olives less than 12 hours after they’ve been picked to be able to sell at a premium. The price increases significantly when the product is exported to markets like the United Arab Emirates and the U.S., where some oils can fetch as much as 120 euros a liter, he said.

“There are two parallel markets for olive oil. One is high quality oil, and one is a discount product,” said the 56-year-old as he prepared for this year’s harvest. “There’s room for us to grow, but only when it comes to the high-end product.”

In neighboring France, producers have been able to charge higher prices by appealing to local sensibilities. Domestic oils sell for an average of 27 euros a liter, and the Chateau d’Estoublon brand comes in perfume-like bottles and sells online for 64 euros a liter.

Back in northern Portugal, a tractor equipped with harvesting equipment approaches olive trees one by one, shaking the trunk and collecting the falling fruits in a wrap-around fan. Baptista says his product is unique enough to avoid the downward pull in market prices.

“Our climate means that we make this olive oil with its own characteristics — very fruity, dry fruits,” said Baptista as the first pressing from this year’s harvest trickled out. “They are characteristics that can’t be found in some other countries,” even if not all consumers appreciate it yet.

--With assistance from Chiara Albanese, Jeannette Neumann, Rudy Ruitenberg, Eleni Chrepa and Richard Weiss.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Chad Thomas at cthomas16@bloomberg.net, Chris ReiterIain Rogers

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.