The Race to Fuel the Buses of Future Is On

The Race to Fuel the Buses of Future Is On

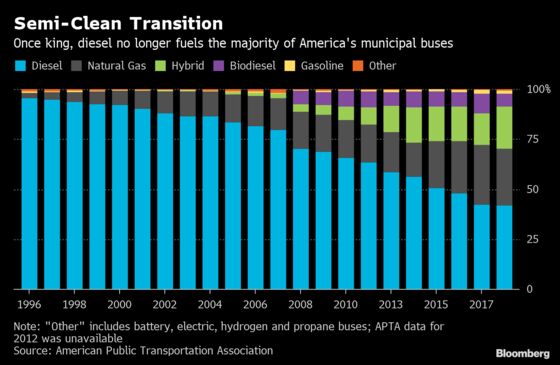

(Bloomberg) -- There’s no denying it: Oil, once the lifeblood of America’s buses and trucks, is no longer king of the fleets. Two decades ago, diesel and gasoline fueled virtually all of the country’s municipal buses. Now, they burn in less than 45%.

A smorgasbord of natural gas, diesel-battery hybrids, biodiesel and electric vehicles worked together to end oil’s reign. Today, they’re all jockeying for the chance to fuel the fleet of the future.

While bus and truck pools account for just a fraction of the vehicles on America’s roads, they’re responsible for generating 80% of the smog and as much as a quarter of the nation’s transportation emissions. That has local and state governments across the country working to overhaul their fleets, touching off a race to gain an early edge and dominate an industry that consumes 1 billion gallons of fuel a year and spends $5 billion annually on buses alone.

“New technologies are coming out more quickly than we can even wrap our head around,” said Erik Johanson, director of innovation at Philadelphia’s main transit authority. “What we’re creating is a new system.”

Gas Gaining

Natural gas is largely to thank for oil’s decline across U.S. fleets. It fuels 29% of the nation’s buses now, up from less than 19% a decade ago. And it has economics on its side: The price of cleaner, gas-fired buses has reached parity with diesel ones -- and can be even cheaper with federal grants.

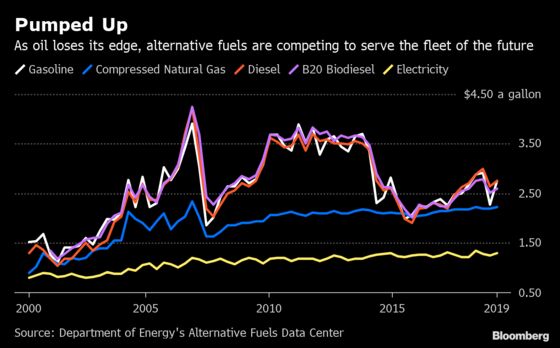

The fuel itself is also less expensive, said Floun’say Caver, the interim chief executive officer of the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority. Since 2015, the Cleveland agency has spent nearly $70 million on 133 compressed natural gas -- or CNG -- buses, which now make up about 40% of its fleet. It’s a worthwhile price considering the authority pays about $1.35 a gallon less at the pump compared with diesel, Caver said. He estimated $75,000 in savings over the 12-year life of a typical bus.

Gas meanwhile emits 22% fewer greenhouse gases than diesel and 29% less than gasoline, according to a report for the California Energy Commission. “Doing the right thing,” Caver said, “also has the economic payback.”

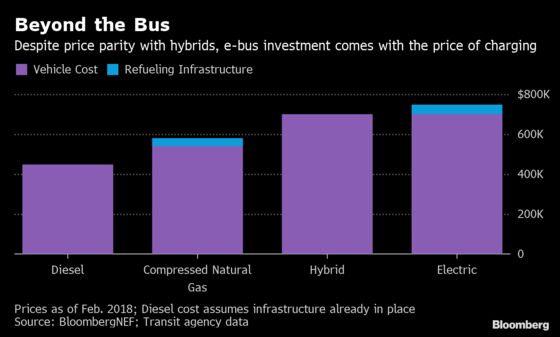

The same fleet operators, however, are still trying to figure out how to pay for the gas pipelines and filling stations needed to keep CNG vehicles on the road. In Atlanta, one new CNG station cost almost $16 million. At that point, “the bus is the least of your worries,” said Tom Young, assistant general manager at the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority.

Young’s authority has converted 75% of its buses to run on CNG, and even he was hesitant to say whether the fuel could take over an entire fleet. “It’s definitely possible,” Young said, “although business wise, I don’t know if it’s something we really want to do. It takes away any flexibility.”

One make-or-break moment for CNG, he said, will be whether the U.S. extends an alternative fuel tax credit. It has been passed by a U.S. House committee but may face objections in the Republican-controlled Senate. If extended, investing in CNG is a “no-brainer,” Caver said.

The E-Bus

While electricity only drives about 0.1% of bus fleets today, some transit agencies already have their eyes set on emissions-free power as the fuel of the future. Johanson, at Philadelphia’s main transit authority, calls EVs the “game-changer” in the transition from diesel. Filling up on power costs about $1.30 per gallon-equivalent, making it the cheapest among competing fuels.

Proterra Inc. has already seen 25 of its battery-powered buses hit Philadelphia roads last month. Another 10 from NFI Group Inc.’s New Flyer are scheduled to arrive in 2021. These first deliveries are a litmus test of sorts for battery-powered buses. “There’s a lot at stake here,” Johanson said.

Just like CNG, electric buses face an infrastructure challenge. A lot of people “think this is just plugging a bus into the wall,” but it’s more complicated, Johanson said.

From needing “a massive amount of power” to paying for the costs of charging stations on top of the buses themselves, agencies are buying into a “complete system” when they go electric, said David Warren, director of sustainable transportation at NFI. Despite the long-term cost savings, the multimillion-dollar, upfront investment is a hard pill to swallow.

“Infrastructure is absolutely a huge investment,” he said. “It’s much more than the bus.”

The e-buses available today also haven’t been thoroughly proven to handle the mileage and wear that’s demanded of a city bus, said Young, from Atlanta’s transit authority. And they can take anywhere from 3 to 9.5 hours to recharge, according to Proterra’s website.

This may actually be the biggest bull case for CNG buses, which could serve as a gradual bridge from diesel to electric -- a transit agency’s way of biding its time until battery costs come down more, Warren said.

The Little Guys

And then there are the underdogs. Biodiesel fuels 6% of buses today. What was once seen as one of the most promising alternatives to oil in the transportation market has now been relegated to a rather niche market. The fuel only makes sense for an agency trying to cut some emissions for cheap. Its share of the fleet market has actually shrunk in recent years, from more than 9% in 2017.

Diesel-battery hybrids, however, are striking the right chord with some fleet operators. They cost about $700,000 a bus, according to two transit agencies. That compares with electric models that can cost around $900,000, said John Lewis, CEO of the Charlotte Area Transit System. The big plus: You don’t need to build out an entire network of charging stations for these because the diesel motor helps charge the batteries.

At the end of the day, the price of infrastructure is going to be what dictates the fleet fuel of the future, according to Lewis.

“The bus technology isn’t a question -- it’s the fuel,” Lewis said. That’s the biggest issue transit officials face in transitioning fuels, he said, because “I can’t take 300 buses every night down the street to a fueling center and then bring them back for the next day.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Gerald Porter Jr. in New York at gporter30@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Lynn Doan at ldoan6@bloomberg.net, Steven Frank

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.